The Fence That Broke Brentwood: A Country Club’s Barbed Wire Ignites War

The prison-like partition mysteriously sprung up along scenic San Vicente Blvd. without warning. Says one homeowner: ‘It’s like I live next to Sing Sing!’

Nicole LaPorte wrote about the 19 press tour stops Hollywood publicists care about now, the spec script market comeback and how Hollywood DEI is now D-I-E.

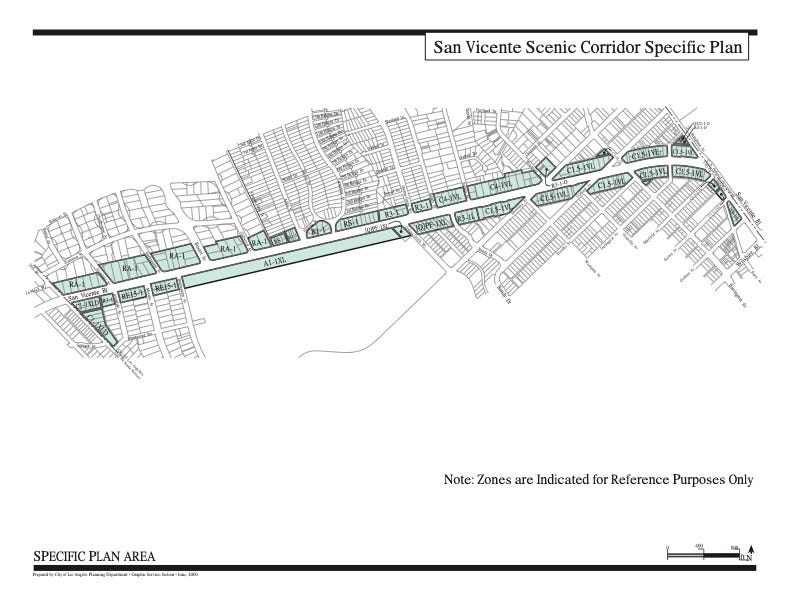

The two-mile stretch of San Vicente Blvd. between Federal Ave. and 26th Street in the area of West Los Angeles known as Brentwood isn’t just a leafy, quasi-suburban oasis of boutique cupcake shops, glitzy trattorias and gated villas that nonetheless styles itself as an understated Connecticut town. The area, known as the San Vicente Scenic Corridor, is a “protected Scenic Highway,” according to the Los Angeles City Planning Commission — one whose every new sign and lighting fixture is scrupulously vetted by a board of Brentwood residents and design professionals operating under the city’s Planning Department. “If monument signs are illuminated, glare must be carefully controlled and lighting sources concealed,” reads one of many stipulations in the Design Guidelines adopted in 1992 and still in use.

Restaurants in Brentwood (median home price: $3.5 million) that want to install neon signs cause heart palpitations for the board. Billboards? Please — put them up in Westwood. As for the sacred kaffirboom coral trees that line the grassy median on San Vicente, where a trolley line once transported Angelenos to the sea, a local non-profit raises $500,000 a year to maintain them.

Which is why when a three-quarter-mile stretch of chain-link fence topped with three tiers of barbed wire was installed by the Brentwood Country Club on its San Vicente perimeter recently, locals were more than a little miffed. “It’s like I live next to Sing Sing!” remarks one. “You can’t change the tenor of the neighborhood arbitrarily, that’s why we have zoning laws. Who approved it? How did it happen? Everyone is just mystified. If I lived across from that in my $15 million home I’d be losing my fucking mind. It’s bad enough I have to drive by it.”

Among those eight-figure homeowners who might be losing their minds over this insult to San Vicente Blvd. are some of the city’s and the industry’s (even the country’s) most powerful figures, from Bob Iger and Dana Walden to Arnold Schwarzenegger, LeBron James, Conan O’Brien, Amy Pascal and former Vice President Kamala Harris.

The aggressive new barrier is all the more glaring because trees and vegetation that had shrouded the original fence it replaced have been removed. And whereas it was possible to peek through the older chain-link fence, the new one is sheathed in hideous dark green vinyl, adding to the Keep Out vibe. Worse: The new fence has been extended out toward the street by a few feet, encroaching onto the dirt running path that gives the boulevard a Central Park Reservoir vibe.

Many locals (well, those who aren’t members) already resent how much green space the BCC — which costs a reported $200,000 to join and whose members include Steve Levitan, Neal Moritz and Dan Aloni — occupies in the area (127.94 acres to be exact), where there are only a few, very small parks for residents. Not to mention that due to archaic regulations, private country clubs in L.A. like the BCC pay only a tiny fraction of the property taxes they should, which means that Brentwood residents — and other Angelenos — are subsidizing the club through their own tax dollars.

Malcolm Gladwell did the math on this on his Revisionist History podcast, using the L.A. Country Club as an example, and figured that while that club should be paying around $90 million a year in property taxes based on the worth of its land, it in fact pays closer to $200,000. As for the BCC (on the podcast, Gladwell discusses running around the club on its exterior path): Last year its tax bill was $171,202, according to public records, the same tax bill as a $14.3 million home — of which there are scores in spitting distance.

Stephen Billings, chairman of the San Vicente Design Review Board, says he had no idea about the fence until contacted by The Ankler. “We never would have approved barbed wire, not in a million years,” he tells me. “Thats not the look we’re trying to have.”

This video taken on Oct. 20 shows the fence going up along San Vicente Blvd.👇🏼

Billings says that last January the BCC — which was opened in 1948 by a group of Jewish investors as an alternative to the Hillcrest Country Club, then the only Jewish country club among L.A.’s historically restricted clubs — presented plans to add 40 feet of golf course netting along Burlingame Ave. as a safety measure. Residents on that street are “always getting pinged” by golf balls, Billings says. That plan was approved. But there was no mention of new fencing on San Vicente Blvd.

When asked about the fence, Thorsten Loth, general manager and CEO of the BCC wrote in an email: “The club is engaged in a safety and beautification project. That project includes removing dead landscape, removing trash and debris, replacing the fence, and finally landscaping.”

Related:

But the “beautification” means a major eyesore for Brentwood residents, some who are new transplants still reeling over the Palisades fire that burned their homes and licked dangerously close to others — and also triggered a separate kerfuffle over landscaping rules. The state of California is proposing to require all homes in a “Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zone,” which is most of Brentwood, to create a five-foot-wide “ember resistant” perimeter around their home — meaning the removal of most vegetation, shrubbery and trees that are not well-maintained in that area.

It all adds up to less greenery and foliage in a neighborhood whose allure (not to mention property values) has always hinged on its leafy feel. As a result, residents are becoming resisters, as I learned from my conversations with frustrated homeowners, neighborhood representatives, and a real estate attorney with insights about who’s right, who’s wrong and ultimately, who has enough power to assert their will over the future of Brentwood’s bushes.

Zone Zero Woes

California’s so-called Zone Zero legislation, which could go into effect as soon as the end of December, has residents in Brentwood (and in Altadena, over on the opposite side of the city) so enraged that a Zone Zero meeting at the Pasadena Convention Center in September lasted five hours. Last month officials from Cal Fire and the state’s Board of Forestry and Fire Protection descended on Brentwood and Altadena (both designated high burn areas) on a damage control mission — to no avail.

“We have actually worked with scientists who study wildfires in urban areas, and it’s density that is the biggest contributor, not vegetation,” says Brentwood Homeowners Association board member Joel Ball. “In a lot of cases, vegetation can help prevent the spread of wildfires if it’s the right kind. So we just think it’s misguided. It’s kind of taking a sledgehammer to a problem that needs a little bit more nuance.”

Zone Zero also poses major costs to property owners. “It can costs thousands of dollars to have a tree taken out,” Ball said. Zone Zero was passed into law in California in 2020 but has hit hurdles due to implementation complexities and public pushback. After the January fires, Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order directing the California Board of Forestry and Fire Protection to expedite the adoption of the law by the end of the year, but it’s unlikely that deadline will be met amid ongoing controversy.

Senate Bill 79, which Newsom just signed, is another blow. The landmark bill overrides local zoning and, starting next July, will allow the development of buildings up to nine stories high near transit stops. Brentwoodians are fuming that the law allows exemptions for some neighborhoods, such as Beverly Hills, but leaves Brentwood high and dry. “It’s just not a productive way to legislate,” Ball says. “We wrote to the governor to oppose it because it’s going to increase the density in a very high fire zone. But they didn’t listen.”

No, no, not that anyone in Brentwood would call themselves a NIMBY (a Not in My Backyarder). That’s for the residents of adjoining Santa Monica, where just two miles down the road on Ocean Ave., and a few blocks from the Hollywood-soaked Carlthorp School, L.A. County was preparing to open two homeless housing projects for individuals battling “severe mental illness” in former senior assisted living facilities. The properties are nestled next to multi-million-dollar condominiums with stunning views of the ocean and bluffs, and are within walking distance of the stately, star-gridlocked north of Montana neighborhood.

That project has been paused due to backlash from Santa Monica residents (what’s up, WhatsApp groups!) and city officials.

Yet the other headaches live on, including the most spikily visible one: Brentwood Country Club’s barbed wire fence.

‘Please Pardon Our Appearance’

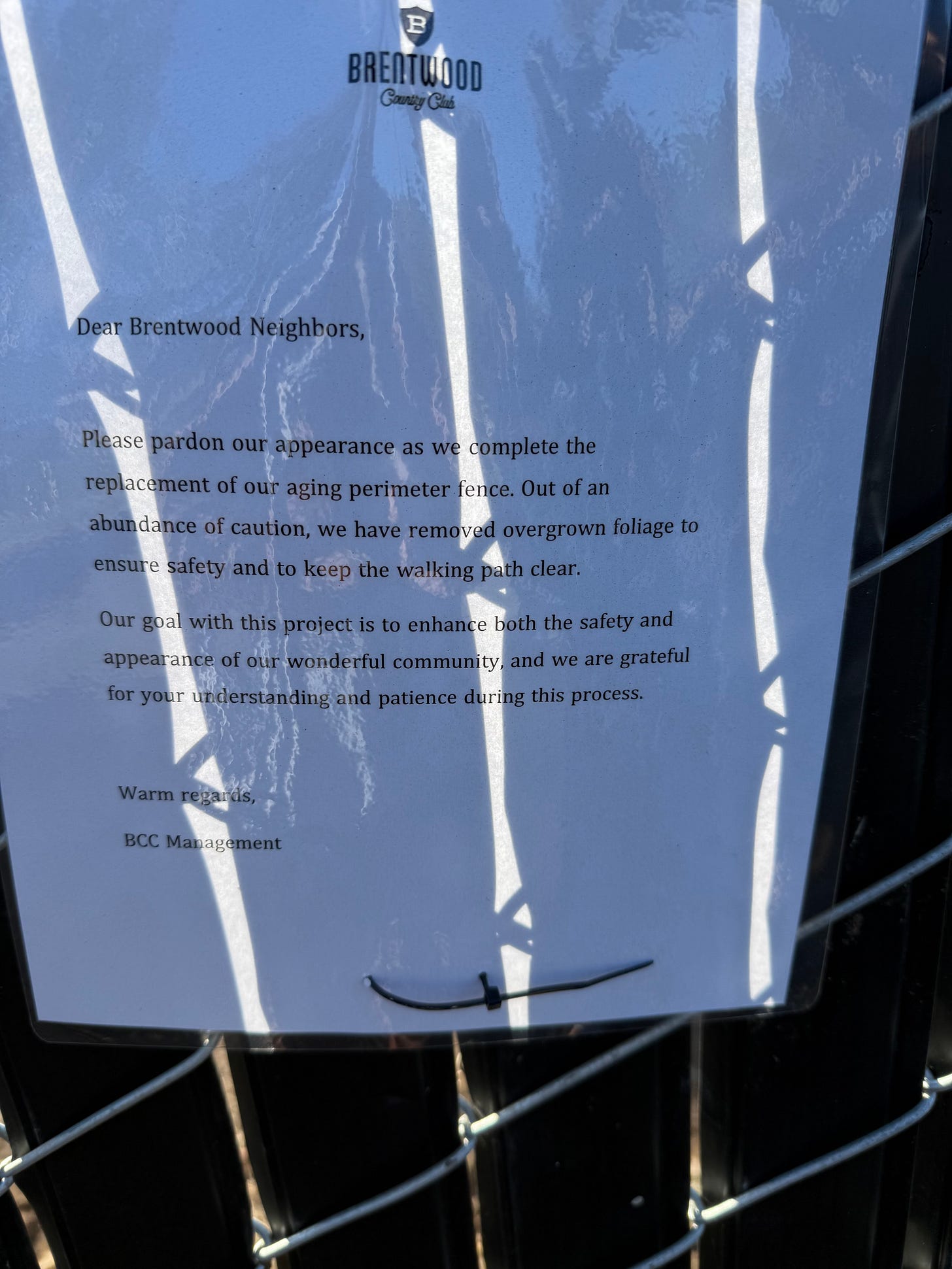

“It just feels like a slap in the face as far as any sort of zoning laws or any sort of caring about the area,” says Mary Kallaher, a 10-year Brentwood resident who adds there was no communication to homeowners from the Brentwood Country Club leading up to the fence’s construction. Adding insult to injury, about three weeks ago, the club posted a leaflet on the fence that began: “Dear Brentwood Neighbors, Please pardon our appearance as we complete the replacement of our aging perimeter fence. Out of an abundance of caution, we have removed overgrown foliage to ensure safety and to keep the walking path clear.”

“It’s just like, ‘Oh, let’s go print [the letter] off the printer and stick it on the wall,”’ says Kallaher, who — along with several neighbors — has taken to writing Councilwoman Traci Park. (No response yet.) Group chats have sprouted up where residents share screen shots of city planning ordinances and photos of the fence construction.

Many Brentwood residents have likened the imposing barrier to Guantanamo Bay, or, more realistically, a minimum security prison fence. “I joked the other day that if we peek through we might see Ghislaine Maxwell walking by,” says one.

A letter from the club to the Brentwood Homeowner’s Association obtained by The Ankler said that the new fence extends out into the club’s property and allows the club to “actually take care” of the foliage “without exposed liability.”

“The foliage will certainly grow again over time, but the outside of the property is city property, and therefore we are not allowed to plant anything there,” the letter states. “Trees that are taking [sic] out in the process of installing the new fence are dead trees and foliage only and vines that are intertwined with the fence that was in certain sections torn and posed a security and safety risk. The new fence is 8ft high while the old one was 6ft in height and will actually better protect from errand [sic] shots onto SV.”

The issue, residents surmise, is less about “errand” golf balls — which, aside from bad putts, no 8-foot-high fence will prevent from flying into the street — and more about keeping unwanted visitors from jumping the fence. “Having a fence there is not new,” one Brentwood resident wrote anonymously to the Ankler. “The overgrown ivy along the old fence was a problem because there were ditches along the fence where homeless people sometimes slept. Also, trash collected within the ivy so it required frequent clean-up.”

This week the Brentwood Homeowners Association emailed out an update on the fence, stating that “recent homeless encampments, chairs and tables chained to the fence by food trucks, and dead or dying vegetation prompted the Brentwood Country Club to clean the area surrounding its property and to replace the fence. The new fence is the same as the prior fence, but with green slats to prevent chairs and tables being left chained to it overnight. We all agree that without the vegetation and trees, the fence is harsh and unsightly. The Club has told BHA that they are currently drafting a landscape plan for the fence. It will be maintained by the Club, not the City.”

No mention was made of the barbed wire, or the fence being higher or pushed out into the pedestrian zone. “This email is full of shit,” noted one resident.

A search of the city’s Department of Building and Safety site shows that the BCC was issued a permit for a fence last June. But residents are wondering how barbed wire was approved given that it is largely prohibited in L.A., including for commercial properties and “light agricultural” zones, which is how the San Vicente perimeter of the club is categorized, according to a city planning map. Another question: Who approved the permit?

Traci Park’s office, including her communications director, did not respond to multiple emails requesting comment from The Ankler. A media representative for the City Planning Dept. did not respond to written questions by press time.

Plenty of Rules, No Enforcement

The fence is completed, but residents who live closest to the atrocity are still pushing back and mulling further action. “It’s one thing to complain, but there needs to be action,” says one, indicating a civil lawsuit may be on the horizon. One point of discussion is to leverage the prescriptive easement angle, a legal concept that allows individuals to acquire certain rights over someone else’s property through continued and uninterrupted use — such as the running path along San Vicente. Proving that barbed wire is illegal along the San Vicente corridor is another.

Easement disputes are common, particularly when fences and walls are built, says one real-estate attorney who requested anonymity to speak about a hot-button community concern. Land can be adopted for use by one party — say, a walkway between two homes — with the unspoken blessing of the other party, but then that party may cry ownership and build a fence. “I don’t know what the conditions of use are, or whether there’s been a generalized reservation of rights,” the attorney says. “But there could be an argument that over the last 40 years or however long, that path has always been used as a pedestrian footpath.

“The problem with prescriptive easement is that you have to make a claim of ownership before you can say, ‘Well, that’s mine,’” the attorney continues, adding, “There are a lot of rich lawyers in that community, they’re going to come up with whatever creative motion they want.”

As for Zone Zero, groups such as the Brentwood Homeowners Association are fighting the fight. That organization is working to certify neighborhoods in the area as fire safe, and residents are looking into possible litigation. “The science tells us it doesn’t make sense, but they’re ignoring it because they have to come up with something,” Thelma Waxman, president of the BHA told the Los Angeles Times. “If I’m going to go to my members and say, ‘O.K., you need to spend $5,000 doing one thing to protect your home,’ it’s not going to be to remove hydrated vegetation.”

This past spring, after the Palisades Fire blazed so close to Brentwood that many residents were under mandatory evacuation orders, and others underwent costly remediation, the BHA invited Jon Keeley, a research scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey and a professor in UCLA’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, to speak about the issue. Keeley debunked the notion that vegetation was the biggest contributor to spreading urban wildfire.

“We’re just concerned that this is really being driven by the insurance industry, to give them an opportunity to raise rates for people who don’t comply,” said Ball. “It’s profit-oriented rather than science-oriented.

“The feeling is, this is just not going to work. People are not going to be able to do this. Many can’t afford it and many are just going to say, ‘This is ridiculous. I’m not taking trees down that we’ve worked to build up in our neighborhoods and our homes.’”

As for the golf club’s fence, Billings says despite the San Vicente Design Review Board’s best efforts to keep the area picturesque, “there are a ton of violations because the city doesn’t have enough enforcement. So we can make rules all day long, but there’s nobody to enforce them.”

He mentions a neon sign that recently went up outside a new local restaurant. “They knew it was prohibited. We just have to live with it.”