MoviePass Is Back (Really). This Time, The Bet Isn’t On Tickets

For the first time, co-founder and CEO Stacy Spikes details the company’s collapse and comeback attempt through its own predictions market

Crowd Pleaser from Ankler and Letterboxd covers audience and moviegoing. I wrote about what the Marty Supreme Wheaties box says about fandom, the small-town theaters fighting against studios and scooped how Paul Thomas Anderson landed in Fortnite. Email me at matthew@theankler.com

There are no second acts in American lives. Just don’t tell MoviePass co-founder and CEO Stacy Spikes.

Spikes’ roller-coaster ride with MoviePass began in 2011, when the brand launched as a movie-theater subscription service that charged a flat monthly fee for up to one movie per day at chains including Regal and Cinemark. At its peak in 2018, MoviePass had about 3 million subscribers. But after Spikes was fired in 2018, and the company went bankrupt due to one of the most ridiculous promotions in the history of moviegoing (more on that below), it seemed to be the end of the line.

Then, in 2021, Spikes — in a redemption arc he likens to Steve Jobs at Apple and Michael Dell at Dell — bought back the assets of his company out of bankruptcy, once valued at around $500 million, for $140,000.

“There have been these times where the founder’s vision, or having people who were so passionate about the product, really just doesn’t beat pure capital and people who think they can do it,” Spikes says.

Immediately, Spikes, 57, adjusted the business model to better align with the company’s sustainability goals. (Users can now subscribe to multiple plans, including a $33-a-month tier that allows up to four movies.)

The company had its first profitable year in 2024, tallying $14 million in revenue. But the comeback had its limits.

A former Miramax VP of marketing, Spikes tells me he realized MoviePass’s future couldn’t be built on just movie tickets.

As competitors like AMC and Regal began bundling Premium Large Format (PLF) screenings — typically the most expensive tickets in a multiplex — into their own subscription services, MoviePass, which doesn’t own theaters, couldn’t compete.

“That was when you just ran the math. The exposure is way too high,” Spikes says. It became a “race to the bottom” to see which company could offer the most value in the cheapest possible package.

If MoviePass couldn’t match the big chains, then what? The answer, as I’ve seen before, came from the predictions market, or as Spikes says, “through gamification.”

The speculation market is projected to become a trillion-dollar ecosystem by the end of the decade. If MoviePass could claim even a sliver of that attention, Spikes reasoned, it could offset long-term decline in its core subscription business — a crucial hedge as the theatrical industry continues to struggle.

For the first time, Spikes goes into detail with previously unreported details on Mogul, a new platform under the MoviePass corporate umbrella that he sees as a way to reach Hollywood’s increasingly 24/7, data-obsessed audience — and to compete for attention in a way MoviePass never could. And it doesn’t hurt that young people, particularly men — the same ones who can make or break an opening weekend — primarily comprise the most-engaged traders on other prediction markets platforms, including Kalshi and Polymarket.

“We want to build the first true hub for entertainment speculation,” Spikes says.

In Mogul’s Series A funding, which valued Mogul at a $50 million valuation, Spikes secured $9 million, over half of which came from major players in the blockchain space. In addition, Global Emerging Markets’ Token Fund committed $100 million in capital, though the full extent of that investment is contingent on Mogul hitting certain token-based milestones. It’s all part of Spikes’ intent to build Mogul on Web3 rails, a decentralized method he believes gives companies an advantage over the “hub and spoke model.”

“We believe in that future, and so we wanted to make the capital investment to be prepared for that,” he says.

Here’s what it is, how he got there and what MoviePass does now.

First, The MoviePass Meltdown

MoviePass began simply enough in 2011, when the New York-based brand offered customers one movie per day for $30-$50 per month. In 2016, as theater chains like AMC Theatres bristled against Spikes and fellow co-founder Hamet Watt, the duo accepted outside help in the form of a new CEO, Mitch Lowe, and a new majority stakeholder, analytics firm Helios and Matheson.

Spikes stayed on as COO at the company he built and was left to watch (eventually completely from the sidelines after his firing) as Lowe and Ted Farnsworth, the Helios and Matheson chairman, offered a staggering movie-a-day for $9.95/month. In 2017, MoviePass — which was aiming for 100K subscribers by the end of the year — became a phenomenon, hitting that goal in 48 hours and tacking on another 75K the next day. The only issue with the company that routinely drew comparisons to Netflix due to its disruptive nature: It made no financial sense. MoviePass lost $14-$20 per subscriber theater visit, which — since the company failed to cut wholesale deals with theater chains — meant funding each customer visit. MoviePass hemorrhaged $40-$50 million each month.

Amid all this came tales of Hollywood excess, including costly parties at Sundance and Coachella, and an investment in John Travolta’s notorious 2018 flop Gotti, which was promoted at the Cannes Film Festival with a lavish shindig featuring a performance from 50 Cent.

“I got the Sundance Party that they did, but why would you do a music festival and why would you spend a million dollars on a music conference?” says Spikes, who claims he warned against the $9.95-a-month offering, but was ignored.

Around that time, shit really began to hit the fan. As detailed later by the Federal Trade Commission in 2021, MoviePass allegedly went to “great lengths” to “deny consumers access to the service they paid for while also failing to secure their personal information.” In one example, MoviePass reset the passwords of the app’s most active subscribers under the false claim that “we have detected suspicious activity or potential fraud” on the accounts. When those users tried to reset their passwords, they were stonewalled due to unspecified “technical problems.” In another instance, MoviePass blocked most users from seeing 2018’s Mission: Impossible — Fallout after the company was locked out of its line of credit by its bank.

The whole thing came to a head in 2020 when MoviePass filed for bankruptcy. Lowe and Farnsworth were later indicted for securities fraud and separately pleaded guilty to the charges, which included lying to investors while masking losses through tactics such as the Mission: Impossible fiasco. They await sentencing. “Mitch Lowe is a good man with a history of good deeds,” David Oscar Markus and Margot Moss, Lowe’s lawyers, said in a statement early last year. “But, like all of us, he isn’t perfect. He admitted his misconduct in this case early on and is doing everything in his power to make up for it.”

“Mr. Farnsworth was anxious to accept responsibility for his conduct,” Sam Rabin, Farnsworth’s lawyer, said in his own statement last year upon Farnsworth’s guilty plea. “The most important step in doing that was to plead guilty to the crimes with which he was charged. He did that today.”

After all that, Spikes holds the reins once again. Which makes it all the more intriguing that the co-founder has opted to go in an entirely new direction.

“In our mind,” he says, “MoviePass 1.0 lets you save money. MoviePass 2.0 lets you make money.”

Hollywood’s Stealth Gambling Circus

I’ve covered the prediction markets space as it relates to Hollywood, and it’s a doozy. And Hollywood’s quiet flirtation with them has become one of the industry’s strangest side economies.

To understand how granular — and lucrative — these markets have become: A group of Rotten Tomatoes traders who bet on films’ RT scores use a method called the “Peter Gray Test.” If Gray — an Aussie critic by night, full-time retail worker by day — doesn’t like something, it’s probably really bad. Last summer, Gray was one of the first four critics to screen Smurfs, and he gave it one star. The traders wagered heavily against the film, which ended up with a rating of just 21 percent on the review aggregation site, scoring four- and five-figure windfalls off Gray’s opinion. They made more money off Gray’s review than Gray did himself.

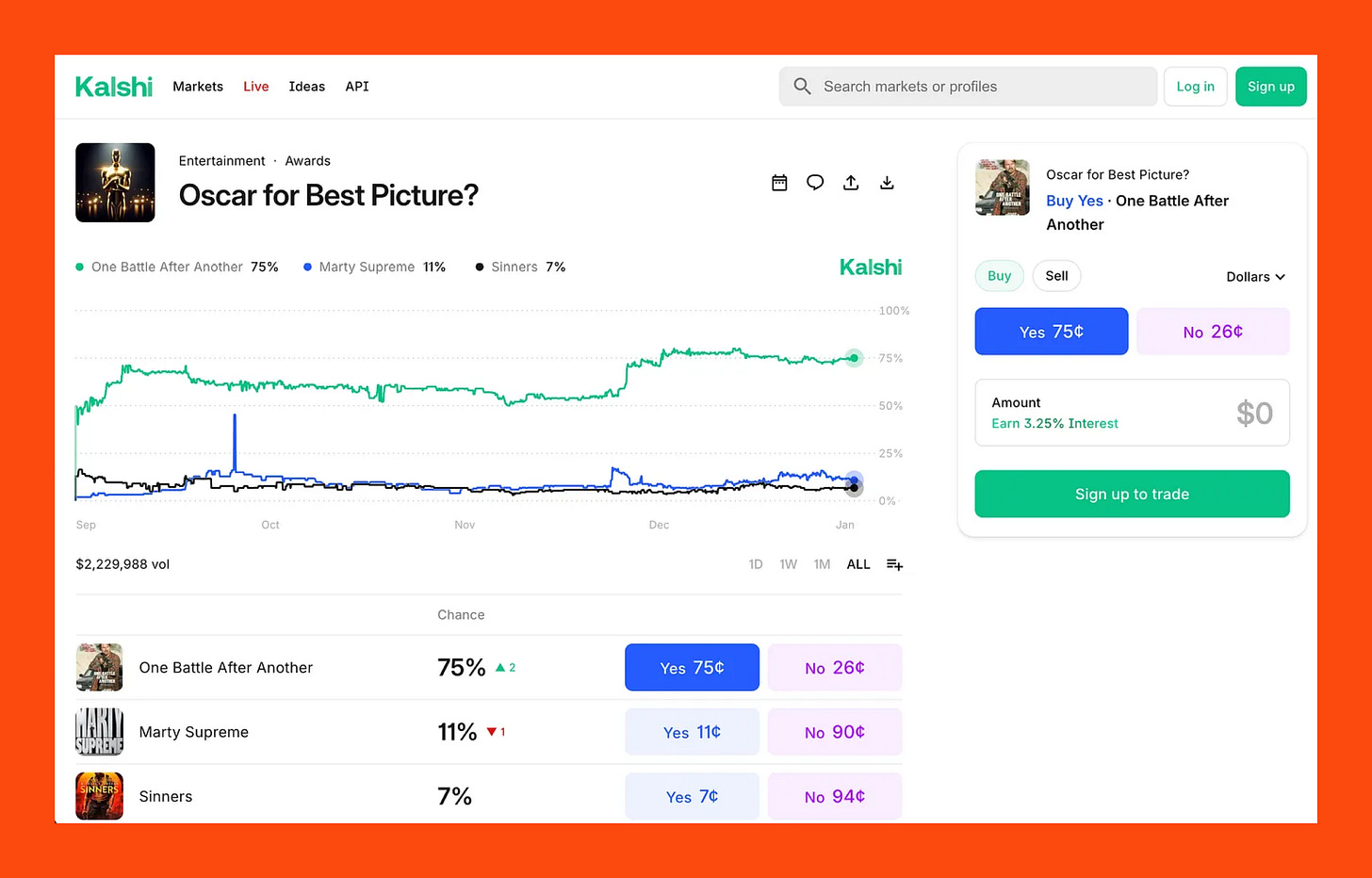

When I interviewed Kalshi CEO Tarek Mansour in January last year, he said the company would be pushing entertainment markets “pretty aggressively for 2025.” That declaration turned out to be mostly false, save for a Timothée Chalamet Oscars flyover ad in L.A. the day of the ceremony. Kalshi added sports wagers later that same month; the sector went on to account for 90 percent of Kalshi’s trades during the fall, and the company now has a $11 billion valuation.

Still, entertainment markets punch above their weight. Just weeks ago, Kalshi set a record with $3.8 million wagered on Rotten Tomatoes outcomes for Avatar: Fire and Ash. Polymarket, which operates internationally, has logged nearly $20 million in bets on the film’s box office. Last year came the closest thing yet to an “eclipse” — when betting volume approaches opening-weekend box office — with Novocaine, whose $1.88 million in wagers amounted to more than 20 percent of its $8.7 million North American debut.

Hollywood has seen versions of this before. In 1996, Wall Street figures Max Keiser and current Lionsgate vice chairman Michael Burns launched the Hollywood Stock Exchange (HSX), a play-money market that let users trade “shares” of actors, directors and films. Attempts to transition HSX to real-money betting in the early 2000s faltered, and a renewed push a decade later ran into industry resistance and a congressional ban on box-office futures.

The concern then was obvious — and remains unresolved: What happens when studios, marketers or insiders can profit from betting against their own movies?

In 2010, when HSX renewed its push, virtually all of Hollywood rebuffed the attempt, and the box office futures ban was enacted into law. “You look at DraftKings, and you look at FanDuel: Why is there not an entertainment version of that?” Burns told me back in 2024.

Since then, though, Kalshi and Polymarket have blown the doors open. Polymarket operates internationally (though users in the U.S. can access it through a VPN), allowing it to offer box office wagering, which regularly attracts millions of dollars in trades. Now, the predictions market is adapting its platform for the U.S. after settling regulatory issues with the FTC. And Congress never accounted for Netflix streaming chart bets (they exist) and RT betting.

Spikes views those prediction markets as the “evolution of social media” — a way of moving past the pollution of social media by creating an ecosystem of people who have real skin in the game. And as HSX once sought to be, he wants to be the DraftKings/FanDuel/Polymarket/Kalshi version of it for entertainment.

What Is Mogul?

As of now, Mogul sits in its beta phase as Spikes and his team test the platform during its first holiday season. Spikes describes Mogul as a “hybrid” between prediction markets and daily fantasy sports (DFS), allowing users to act as a general manager with a set salary cap to spend on specific films, directors and actors.

Mogul is not intended to be a competitor to the Kalshis and Polymarkets of the world, which Spikes likens to the NASDAQ and New York Stock Exchange. He wants to be the specific category or volume play that feeds into those larger exchanges, rather than carrying the massive capital and licensing burden required to be a complete marketplace. The goal is also for Mogul to funnel into MoviePass and boost the subscription service. Over 630,000 users were on the waitlist to join the Mogul platform, while roughly 5,000 users played the initial private beta version that launched last May. The plan for Mogul to make money is initially through contest fees for fantasy sports-style competitions, subscription tiers that unlock reduced contest fees and access to limited-entry contests and tokenized trading transactions. Eventually, Spikes hopes studios will sponsor or partner on contests tied to film releases.

Entertainment is not sports — the wagering apparatus is a pebble compared to the ocean of sports betting options out there. In large part, that’s because you can’t bet on film in quite the same way you can on football. (I can wager on what happens on the field. For any number of reasons, I can’t bet on what will happen in a film, although Polymarket did tally $83.6 million on “Who will die in Stranger Things: Season 5?” bets — a controversial market given the ambiguous fate of one lead.)

Spikes, however, argues that while Las Vegas has successfully monetized the awards bucket (Oscars, Emmys bets and the like), no one has capitalized on the attendance bucket — or created a central hub for entertainment data. His thesis is that, as sports data (yards, points, even balls and strikes, as the scandal around MLB pitcher Emmanuel Clase revealed last year) has become gambling fodder, there are entertainment fanatics who would love to get their hands on everything from per-screen averages to sentiment scores, and correspondingly profit from it.

“You can know so much detail and data, and we see the only other place that is as data-rich is sports,” Spikes says. “Well, the closest business that has that level of data that people are predicting and guessing about every Friday is movies.”

The Wager

Spikes grew MoviePass, which, from the beginning, has operated out of a WeWork in New York City’s West Village, on the belief that there was latent interest and enthusiasm for movies. They just weren’t being served it the right way — subscriptions — something he still believes “there’s not enough industry focus on.”

“Hollywood’s problem is not going to theaters or not,” Spikes says. “If you had a subscription business that didn’t require you to bet the farm on Friday night, you’d have a stable world. But what happens is that you don’t have subscribers, so you have to acquire people every single day. You have to acquire those people to come.”

With subscriptions, which are now present at roughly 60 percent of theaters, “people have already paid for something,” Spikes says, and “they want to get value out of it, so they’re going to tune in.”

The one trait you’ll find if you talk to Spikes is that he’s inherently a believer in the movie business. He’ll readily tell you that more people went to see the new Avatar than went to games this entire NFL season.

Does that belief translate to the gambling space?

It’s a big bet.

Now From Letterboxd: Oscar Fever

This week, a look at Academy Awards history

There weren’t always 10 movies nominated for best picture. For most of Oscar history, the Academy Awards’ top honor was capped at five nominees — but in the first year of the Oscars ceremony in 1929, only three films were nominated (the winner was Wings), while in 1935, when It Happened One Night won, it did so in a field of 12. In more recent history, the best picture lineup moved on a sliding scale, where anywhere between five and 10 movies could get nominated, before settling back on the set 10 the Oscars has employed over the last few years (and, no surprise, many film fans have found services like MoviePass or similar subscription-based theater programs to be worthwhile investments to make sure they can catch the whole list).

As we look ahead and wonder which movies might join the list of best picture nominees later this month (Oscar nominations voting starts next week), it’s also a great time to consider when the Academy got things right. As Michael Schulman points out in his book Oscar Wars: A History of Hollywood in Gold, Sweat, and Tears, Oscar nominees tend to reflect Hollywood’s shifting attitudes and viewpoints: 1967 was a watershed year because it marked the transition from the dying studio system, with a decrepit nominee like Doctor Dolittle, to exciting New Wave-influenced features like Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate. Academy members, like the rest of us, don’t know what will stand the test of time; rather, their picks represent a snapshot of current preferences that sometimes sync up with classics that endure through the ages.

In that spirit, Letterboxd put together The Best Best Picture Lineup. It’s a list that sorts every group of best picture nominees by the average rating of all films nominated in the category, with each year represented by its highest-rated film.

It’s likely no surprise to see the movies from 1975 on top, a monster of a year sporting the classics Barry Lyndon, Dog Day Afternoon, Jaws, Nashville and the Oscar-winner, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (one of only three movies to “sweep” the Oscars by winning picture, director, actor, actress and screenplay; the others were It Happened One Night and The Silence of the Lambs). Interestingly, expanding the pool of nominees didn’t significantly affect the averages. For example, Dune: Part Two was the highest-rated film among members in 2024, but even though it was among last year’s best picture nominees, the 2025 class ranks 68th, between 1954 (when Roman Holiday was the highest-rated) and 1989 (when Mississippi Burning was the highest-rated).

As for where the nominees for 2026 might fall, you would think there’s a heavy hitter in the bunch with the presumed front-runner, One Battle After Another, and its 4.3 average. But that’s actually 0.1 lower than Dune: Part Two (which had a 4.4 average). Then again, 2025’s nominees included the polarizing Emilia Pérez, which had a 2.0 average; this year, the slate of Netflix contenders is noticeably stronger, with Frankenstein (3.9 average) and Train Dreams (4.1 average) widely predicted as possible best picture nominees. Still, historically, Netflix’s best picture contenders have a habit of dragging down the overall yearly average for best picture lineups, so if you want to see the higher-rated nominees, you might want to pick up MoviePass and head to the theater. — Matt Goldberg for Letterboxd