John, Yoko and a Cache of Private Taped Phone Calls

Kevin Macdonald's 'One to One' hits Sundance with footage of John Lennon's final concerts ('so fucking good') and a remarkable set of never-revealed audio

Rob LeDonne interviewed the husband-wife duo behind the music of Emilia Pérez, Diane Warren about “The Journey” from The Six Triple Eight, Lainey Wilson about Twisters’ “Out of Oklahoma,” Maren Morris & Kris Bowers about The Wild Robot’s “Kiss the Sky,” and Elton John & Brandi Carlile about “Never Too Late,” from John’s biodoc. He’s at rob@theankler.com

“Everything will be okay in the end. If it’s not okay, it’s not the end.”

These immortal words have long been attributed to the great John Lennon, and if there was ever a time to take them to heart, it’s now.

This week I spoke with director Kevin Macdonald about his and co-director Sam Rice-Edwards’ fresh and energetic documentary-slash-concert film One to One: John and Yoko. Screening at Sundance next week after premiering last year at the Venice Film Festival to rapturous reviews, it is simultaneously a portal into the past while also being startlingly relevant and eerily prescient.

Through a treasure trove of archival footage centered on two benefit performances Lennon and Yoko gave in New York in 1972 — also titled One to One, they represented the icon’s final full-length concerts — the film immerses viewers in the culture and conflicts of the era. As I watched it, my phone was lighting up with news alerts about charity concerts being held in response to the immense disaster that has unfolded in Los Angeles in recent weeks.

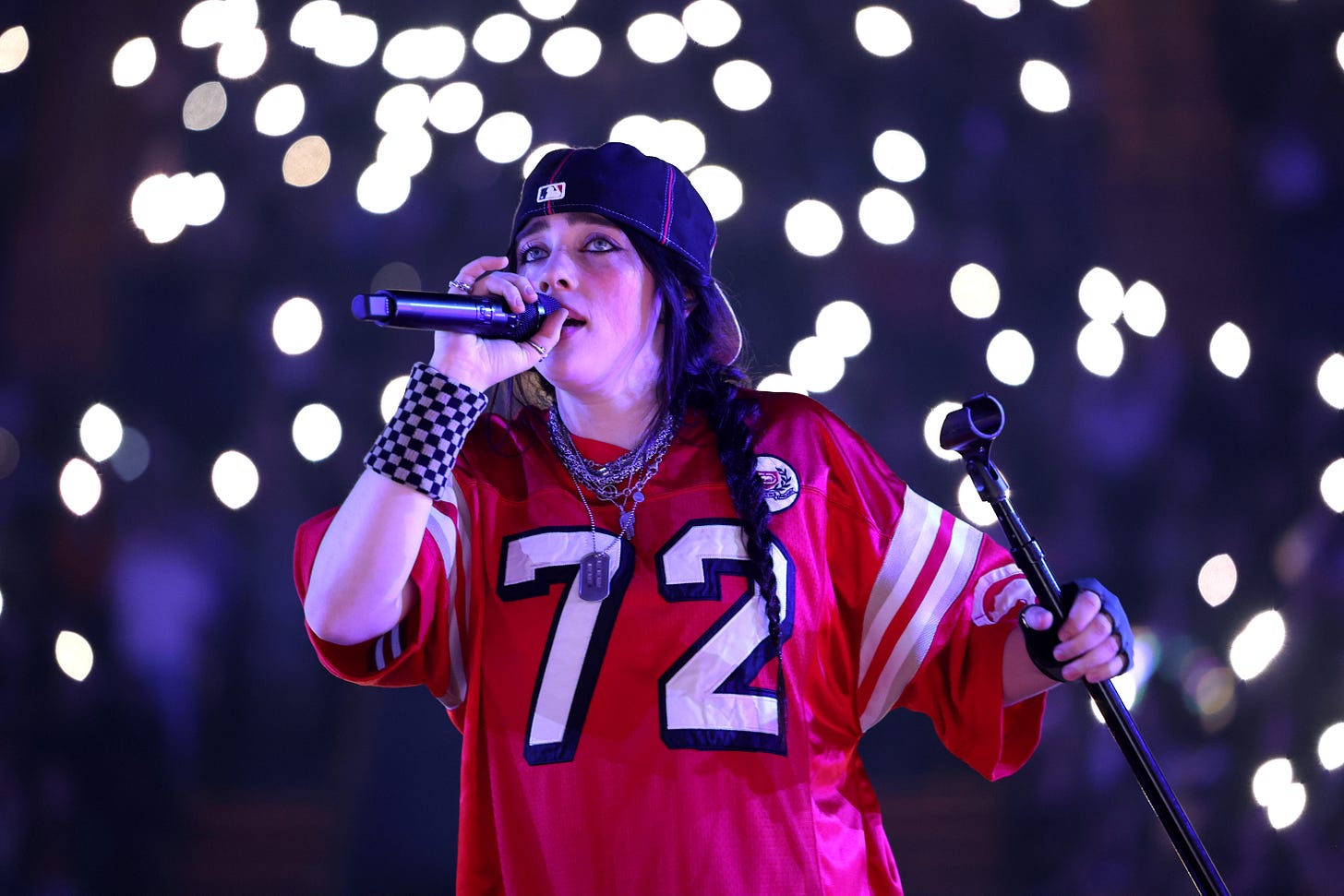

Kicking off this year’s muted Grammy weekend, Live Aid’s FireAid, produced in part by Irving Azoff, is set for Jan. 30 and will feature an array of superstars from Lady Gaga and Joni Mitchell to Billie Eilish and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. The event is expected to draw so many performers and fans, it’s taking place at both the Intuit Dome and the Kia Forum.

With many Grammy events being called off (including Spotify’s annual Best New Artist bash, as well events from the major labels), the ones that are happening have pivoted to focus on fire relief. That includes Friday, Jan. 31’s MusiCares salute to the Grateful Dead (which has always been a fundraiser for industry professionals), the pre-Grammy Gala hosted by Clive Davis on Feb. 1 and the Grammys themselves on Feb. 2 at Crypto.com Arena.

Though the Grammys and Oscars have always given very different vibes, the film Academy is surely watching its music-industry colleagues for cues as to how to put on an awards show at such a sensitive time — AMPAS leadership has affirmed that the March 2 ceremony must go on, and today is the last day of Oscar nominations voting, with the nominees to be revealed this coming Thursday after two separate fire-related delays.

Thursday also marks the kickoff of the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, which will see multihyphenate megastar Jennifer Lopez tromping through the snow to promote her Kiss of the Spider woman remake, directed by Bill Condon. (My colleague Richard Rushfield spoke to fest director Eugene Hernandez about this year’s event and Sundance’s future.) As always, the fest also features a slew of major music documentaries. Along with One to One, there are films about stars from Selena (remember when J. Lo played her 25 years ago in Selena?) to Jeff Buckley and Sly Stone (whose biopic was directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, a fest regular and an Oscar winner for 2021’s Summer of Soul).

I’ve always held The Beatles in high regard, and I’ve interviewed many significant artists about the band including member Ringo Starr (peace and love!), producer Giles Martin and regular Beatles documentarian Peter Jackson. Still, even I wondered what more could be excavated about them after an avalanche of Beatles docs, most recently Beatles ’64 on Disney+. But One to One mines a rich vein of fresh insight, through both the rare concert footage and a box of phone recordings between John, Yoko and the other characters depicted in the film.

Macdonald, 57, who’s an Oscar winner for the 2000 documentary One Day in September, also has several music films under his belt, including Whitney and Marley. So he knows his way around legends. Here’s what he shared about the process of revisiting Lennon’s story.

‘People Who Feel They Can Change the World’

Rob LeDonne: Watching your film, I kept on having this thought of: What John would think of our current era?

Kevin Macdonald: Yeah, when I started making the film and going through the archive footage from late ’71 through to early ’73, the period of the film, it just seemed that every time I saw something I’d think, “Oh my God, this is about now.” It seems like it’s about the world we’re living in, whether it be the political side of it — with George Wallace [who ran for president in 1972] and the parallels to certain other populist leaders in America — or the emphasis on race or the environment and all these things we talk about. It’s incredibly prescient in some way, and maybe this is the wrong word, but it’s also depressing that we’re still talking about the same things. John and Yoko start off feeling like, “We can overthrow the government, we can get rid of Nixon!” And then it becomes, “What can we do just for a few people? How can we actually just change the world a little bit around us?” And maybe that’s what we’re all feeling now.

RL: One of my favorite quotes from the film is John saying, “Flower power didn’t work. So what? We start again.” The idea of soldering on like that, with that attitude, is very inspirational.

KM: There’s a kind of optimism from a lot of these characters, even Jerry Rubin; people who feel they can change the world. People could call it naïve, but it’s actually encouraging and optimistic.

RL: Through your vast research, what did you learn? Did your opinion of Lennon change over time?

KM: I was a huge Lennon fan when I was a kid growing up. I was around 13 when he died. At the time, everything he did went to the top of the charts and everyone was talking about it. He was a hero of my teen years. But one thing I took away now was how incredibly funny he was — so sharp and clever, but on the other side of it he’s so endearing. I also saw how he lived his life as the most famous man in the world at 32-years-old, and despite that, there’s a sort of openness to him, and a willingness to be wrong and learn.

RL: Yes, that struck me too. He says in the film that he achieved it all and had the 70-acre mansion but is happier in his small apartment in New York.

KM: His willingness to embrace that was incredible. And then at the end of the film to embrace feminism and to be the only man in the room at the first international feminist conference, for example. I mean, who else can you think of, not just in the music world, but in the arts world in general, also did that?

RL: How closely did you work with Yoko or (their son) Sean Ono Lennon on this?

KM: I did not have any contact with Yoko because I think I’m right in saying that this is the first project from the estate where she wasn’t directly involved. Sean and I spoke, and I pitched him this crazy idea, and he said, “I think this is the kind of thing my mom would love.” He came to see it in London and gave a few thoughts about it from one artist to another. What was very touching to me is he said, “I think this film captures my mother in particular better than anything else that's out there.”

RL: The film includes a lot of unheard recorded phone calls with John and Yoko. How did you get your hands on them and why did they record their calls in the first place?

KM: Those were priceless. They were really worried that they were being bugged, which everyone says they were. John — or Yoko, actually — thought they should record their own calls because if there’s ever a court case, they could have the evidence themselves. So they recorded their calls and then they were completely forgotten; they were in a box somewhere. But six months into editing, I got a phone call from (Yoko collaborator, producer and director) Simon Hilton who said, “Oh, we just found this box of old tapes from the era you’re making your film about. Do you want to listen to them?” I was like, “Uh, yeah!” I remember listening to them just amazed because you feel it’s their real voices in the middle of ordinary life, not conscious of performing for anyone and just chatting. I learned a huge amount from those tapes.

RL: You’ve had a prolific career, but what was it like to dive into the world of The Beatles, which many people think of as sacred. What made you sign onto the project in the first place?

KM: When I was first approached I said, “Oh God, is there anything else to say about The Beatles?” But I went through the footage and I thought, “I cannot pass this up,” because the material we had was so amazing and so different. Even with the concert we show — The Beatles stopped touring in ’66. They don’t play live ever again, and John only played live a handful of times after that, so the concert footage was the only time he did a whole set, and he did it with Yoko. It is amazing watching him play and just be so fucking good; you’re totally compelled by this man and by his talent. When I first heard it, I thought, this is gold dust, this is the Holy Grail; a singing voice of John Lennon in a way that people haven’t heard before. He’s baring his soul to us. So that was what made me want to do it in the end.