The 'Emilia Pérez' Couple Who Solved a Polyglot Musical Puzzle

Clément Ducol and Camille, the duo behind Zoe Saldaña showstopper 'El Mal,' map out the song's raw power — and their Broadway dreams for the film

Rob LeDonne interviewed Diane Warren about her song “The Journey” from Netflix’s The Six Triple Eight, Lainey Wilson about Twisters’ “Out of Oklahoma,” Elton John and Brandi Carlile about “Never Too Late,” their title track for John’s biodoc, and Maren Morris and Kris Bowers, who collaborated on The Wild Robot’s “Kiss the Sky.” He is at rob@theankler.com

“There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

It has been the latter most recently, with decades’ worth of destruction in Los Angeles, as if you needed me (or whoever coined that quote, dubiously attributed to Lenin) to tell you that. In a multifaceted disaster that has sent shockwaves across the city, a plethora of stories of loss and heartbreak, love and community are unfolding as we speak, block by block. I’ve been through a catastrophic weather event — a hurricane that nearly flooded my family’s home — and it is an unimaginable feeling when absolutely nothing is guaranteed; when numbness and shock take turns with grief and perseverance.

Our hearts go out to so many whose lives were forever altered, including last week’s Notable subject, the legendary Diane Warren, one of countless Angelenos who lost homes.

In the face of the destruction, organizations like MusiCares have sprung into action. “We expect the disaster relief efforts in Los Angeles to be extraordinary, if even just on the basis of how many people lost their homes in the last day,” executive director Laura Segura said on Friday. “MusiCares can help with short term emergent needs for those currently displaced and then longer-term services as we get a handle on the full extent of how music people are impacted.”

Among other impacts, the fires have caused dozens of film and TV premieres, productions and music-related events to be postponed or canceled, and as my colleague Katey Rich has noted, the film Academy extended Oscar nominations voting and pushed back the nominations announcement as well. This newsletter, typically published on Fridays, also experienced a delay and is coming to you Saturday morning.

The awards race feels like a mere blip on the radar right now, but it was just six days ago that Jacques Audiard’s Emilia Pérez scooped up a bunch of Golden Globes, including best musical or comedy motion picture, best foreign film and supporting actress honors for Zoe Saldaña. “El Mal,” performed by Saldaña and co-star Karla Sofía Gascón, won best original song. (“Mi Camino,” Selena Gomez’s playful pop karaoke number from the film, was also nominated.)

Emilia Pérez centers on the personal and political journeys of a trans woman with a dark past as a drug lord in Mexico (Gascon) and the attorney, Rita (Saldaña), who work with her on a charity that helps families find the remains of loved ones killed by cartel violence. “El Mal” cuts to the heart of Emilia’s conflicts and compromises with its poetic and genre-bending takedown of Mexican government corruption. Performed during a gala benefit dinner, with Rita singing in a fantasy and Emilia soliciting donations in real time, it condemns the smug hypocrisy of officials who pretend to support the cause while taking money from the monsters who cause the violence.

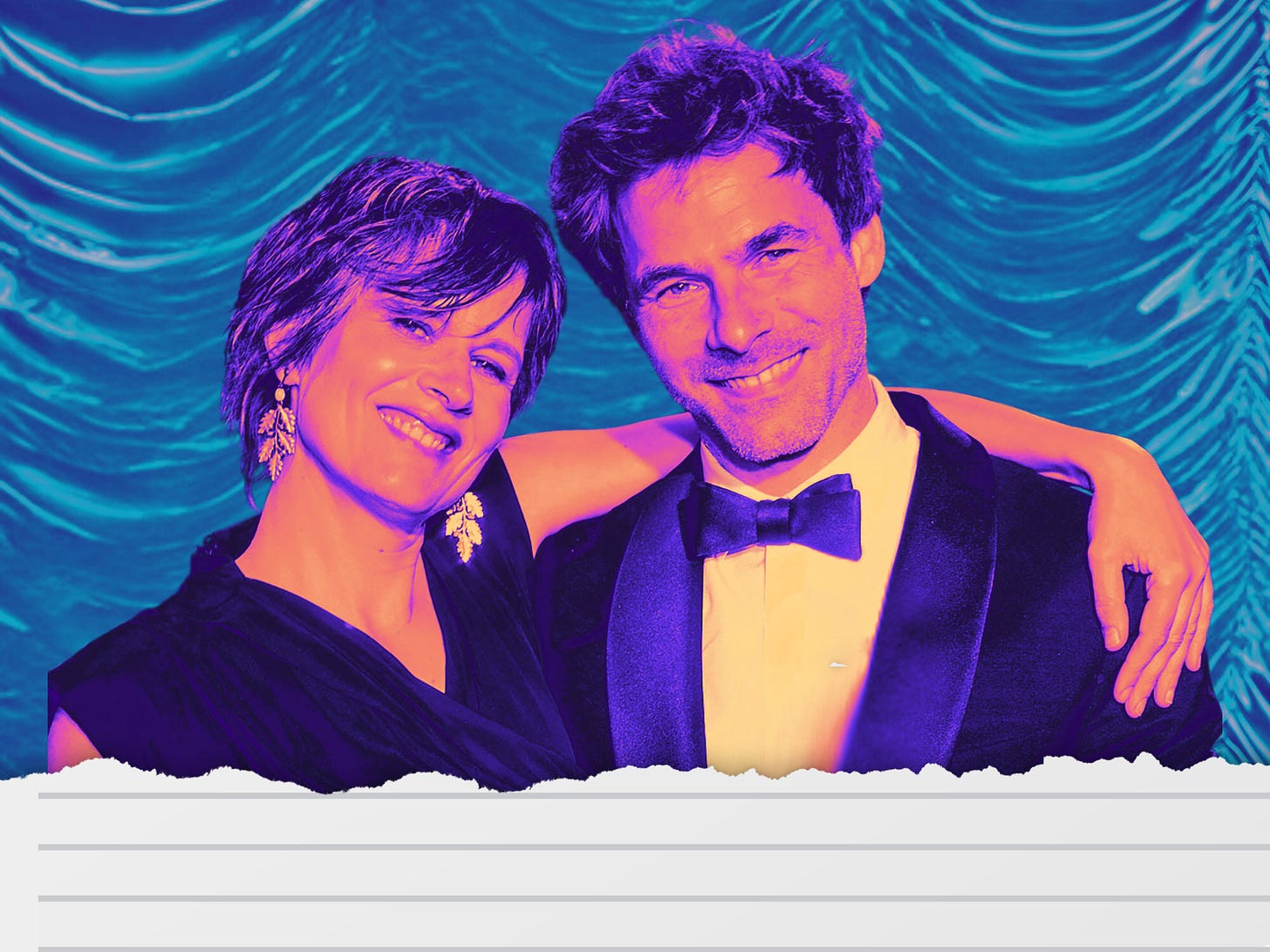

Camille and Clément Ducol, partners in art and life, are the dynamic duo behind the film’s singular music. Camille is a one-name star in their native France, with solo pop hits like 2006’s “Ta Douleur” (she’s also the voice on Ratatouille’s “Le Festin”). For Emilia Pérez, she and Ducol mapped out an impressive and tricky musical landscape, blending complicated themes with a range of genres, not to mention an array of languages.

I checked in with the creative couple, who have a daughter and son at home, about a week filled with high highs and very low lows.

Awards to Apocalypse: ‘Everything Is Fragile’

Rob LeDonne: You both started your week with the Globes win before getting caught up in what everybody in L.A. is going through. How are you and your family doing?

Clément Ducol: We live in Venice, and our neighborhood hasn’t been evacuated. But I think it was very strange emotionally because we had such an amazing experience at the Golden Globes, and then it felt like we were surrounded by the apocalypse. So it’s a very strange feeling. Everybody knows that this Hollywood industry was built on such fragile land. So when you’re given an award, it is so exceptional, and having a chance to celebrate is so exceptional. But we know everything is fragile and temporary, in a way.

Camille: The Golden Globes were a great moment of celebration, but also a moment of great focus because we had a lot of pressure and a lot of expectations, and it was exhausting. We were really happy for the whole team and of course for our music; we felt very honored.

RL: I think the line of the night came from you Camille when you said in your acceptance speech, “This is such an American experience.” Did that just come out? What made you say that?

Camille: Oh, it just came out. I mean, the art of celebration here is very impressive to us; celebrating art, culture and these generations of artists. But having people like Elton John there, I really held back my tears. Someone like him has been part of my life for so long. We were playing his songs at the piano with my brother, who became a pianist, and I became a singer-songwriter. So if I had to summarize everything, that’s what came out.

RL: When I was talking to my friend about Emilia Pérez, I found it hard to describe as both a musical and a film. It’s unique and seems to combine so many influences and genres. It made me wonder if you had any inspirations, musically or personally, that you built off when you were first getting started?

Ducol: There was no inspiration. It was only the story. We were very connected with the story and with the characters. Jacques wanted to build the script within the songs and in music, so the music helps the action move forward. But this is a story of emancipation, evolution, transformation of four different women and the music shifts along with their transformations.

So that explains why it explores so many genres, as the characters are evolving a lot of the time. Rita as a character is quite political, so we thought immediately that Rita would be the rapper, the preacher, and it actually ended up kind of gospel. For Jessi, Selena Gomez’s character, she brought a lot of depth to the character, and we made “Mi Camino” poppy because Selena is a pop artist. So we played with that and with club music and karaoke.

RL: A song like “El Mal” stands apart because it doesn’t have a traditional melody and I’ve seen it compared to songs like Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” with shades of Lin-Manuel Miranda, ’80s rock and even opera. How did you go about creating the song from scratch, because it seems like it’d be a puzzle?

Ducol: Yeah, that is probably the song that gave us the most trouble because the subject matter is so harsh (the hypocrisy of government officials who take money from cartels), and singing about it in front of these corrupt and horrible people was complicated to translate musically. So we were between cynicism, irony, distance and lyricism. But finally we found the tone with this sort of a rock opera. Jacques was also inspired by Prokofiev’s “Cantata for the 20th Anniversary of October Revolution.” But in the end, it’s Zoe’s energy which helped us find the right arrangement.

When it came to editing, the production originally was more electronic, and Jacques told us he wanted something more rock with more rage. So we redid the whole thing live with a rock band in studio, live over Zoe’s performance. So it was a long journey to the final song.

RL: Camille, in your memorable Globes speech you also said: “Songs are like butterflies, even if it’s to the dance of corruption.” What was it like writing about such challenging themes featured in this film? Did the task excite you or give you trepidation?

Camille: When I was writing the lyrics, I felt helped, inspired and protected by the fact that it is fiction. Fiction and song both help you to be more political. It’s like when you use allegories or metaphors to escape censorship. It allows you to be even more direct. But the lyrics are portraits; they’re so real and were pretty much ready a long time ago before we adapted the music, and the portraits stayed the same along all the different stages the song has been through.

I remember demoing the lyrics, and I was crying out of fatigue because it’s very tricky. When Zoe took over, the fact that she dances helps get it out because it’s so violent. But through the music, we can denounce it all on another level; we can absorb it better. And the truth can be said in an easier way.

RL: Would you say it was a catharsis, just getting it all out?

Camille: Like we say in French, you ground it — the kind of energy, electrical energy you don’t need goes to the ground. And “El Mal” is a little bit like that. It’s a healing process, and Zoe puts it to the ground, and at the end the ground is trembling. There’s an earthquake at the end of the song. So it means she really shook, you know? The ground has had something to take on and process.

RL: The film is in both English and Spanish with a French director, to boot. What were the challenges of working on a multilingual project?

Camille: It was a great challenge. Clément lived in Spain when he was a little toddler, but he doesn’t really speak Spanish. I studied Spanish at school, thankfully, so I could write the songs in Spanish. I’m thrilled by languages. I feel languages are music in their own way.

Jacques doesn’t speak Spanish, so he trusts me on the lyrics and phrasing. I composed some and Clément composed others. So my role was to write when it was Clément’s melody and really follow the inflections. Spanish like English has intonations that are really important. So it was quite thrilling. I learned so much about Spanish and Mexican Spanish through the process. The Mexican language is very beautiful, so I tried my best to honor the Mexican accent. It is a very percussive language, which was needed for “El Mal.”

RL: Speaking of Jacques, had you known him in France before this project? How did you come together?

Ducol: We met because of a friend of mine, a French producer named Philippe Martin, who has a production company. Jacques had come to him and said he wanted to do a musical but didn’t know who to do it with. So we met with him, which is already an event because he’s one of France’s greatest directors. It was a dream.

RL: I know you’re still in the midst of this project, but has there been any talk about the future of Emilia Pérez, perhaps on stage?

Ducol: We would love to put Emilia Pérez on Broadway. At the start, Jacques mentioned he was thinking of it as an opera, and of course it became a film. But even when you watch it, it looks like a live performance. As we say in French, Zoe tears off the screen; she’s beyond the screen. It’s like she’s in a theater, you know, she’s on stage. And we would so much love to see Emilia Pérez on stage.

Camille: We’d love a live version, and there have been talks. More to follow . . .