Cousin Collab: Rian & Nathan Johnson Balance ‘Ugliness and Beauty’ in ‘Wake Up Dead Man’

The filmmaker and his composer let me in on the process they’ve developed over decades: ‘We really like imperfection.’ Plus: Listen to an exclusive track from the score

I cover where music & Hollywood meet. I got the scoop from Stephen Schwartz on the future of Wicked, wrote about Japanese Breakfast’s throwback song for Materialists and the return of the sexy TV soundtrack. Reach me at rob@theankler.com

The game’s afoot once again.

Six years after Knives Out introduced audiences to Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig), the enigmatic detective with an unmatched track record solving crimes (and a very specific Southern drawl), filmmaker Rian Johnson is back with another star-studded whodunit: Wake Up Dead Man.

In limited release this week (check here to see where it’s playing near you) before bowing on Netflix Dec. 12, Wake Up Dead Man is perhaps the most thought-provoking entry in Johnson’s comedic mystery franchise thus far. Set in an upstate New York community, it centers on a hapless, earnest priest (Josh O’Connor) who finds himself embroiled in a thorny scandal when his church’s controversial monsignor (Josh Brolin) winds up dead — leaving a proverbial pew filled with suspects (played by stars like Glenn Close, Kerry Washington, Jeremy Renner, Andrew Scott and Cailee Spaeny).

The film combines scenes of scary gothic horror with laugh-out-loud comedy and a ton of modern political commentary. I saw it recently at Netflix’s Paris Theater in New York, and the audience was eating it up — especially a self-referential one-liner about the streamer (which I couldn’t wait to ask Johnson about in my interview below).

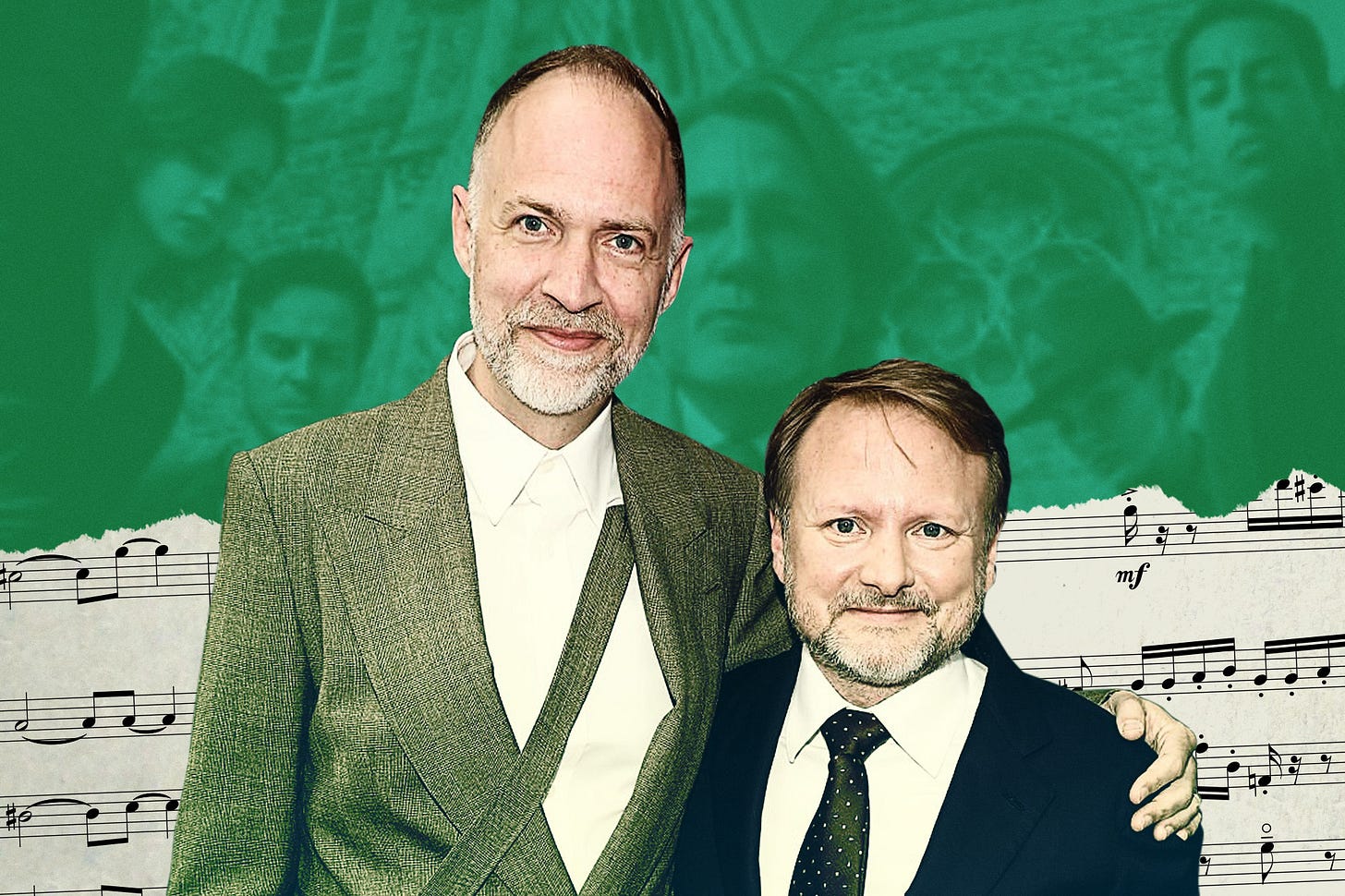

While the tone of Wake Up Dead Man is somewhat new for the franchise, the creative continuity remains largely intact, with Johnson again enlisting the services of his longtime cinematographer Steve Yedlin, editor Bob Ducsay and composer Nathan Johnson, all three of whom collaborated with the filmmaker on 2019’s Knives Out and 2022’s Glass Onion. But if you count all the projects Rian Johnson has ever done — even dating back to his childhood — no one has worked more closely with him than Nathan Johnson, Rian’s cousin. They’ve been together as screen partners since Rian’s breakout directorial debut, 2005’s Brick, where Nathan used everything from wine glasses to filing cabinets to create the score. (The only Rian movie Nathan hasn’t scored? The Last Jedi, which has music from Star Wars legend John Williams.)

As both Rian, 51, and Nathan, 49, told me, their process on Wake Up Dead Man was the same one they’ve developed over the decades. They share a love of “imperfection,” Nathan says, and both relish “the freedom to try anything,” Rian adds. You can listen to an exclusive track from the film’s score below, and be sure to check out the tantalizing tip Rian gave me: “You can solve 90 percent of mystery films knowing one little trick.” Of course, it takes a whole bag of tricks to make a great mystery movie, let alone three. Read on for the Johnsons’ shared creative playbook:

Rob LeDonne: I was trying to think of other examples in Hollywood of a director and a composer being related, and the only example I could come up with was Francis Ford Coppola working with his father, Carmine Coppola, on the music for The Godfather. Since you’re such an anomaly, I’m curious what it’s like to work together.

Rian Johnson: Well, it’s great (laughs). I feel like, typically, when the director hires a composer, you’re thinking, “This type of movie has this type of tone, so we’ll get this type of composer who does this sort of thing.” So one of the great benefits, beyond the shorthand and just working with someone I love, is that with each new project, we have the freedom to try anything. It’s a journey we’re on together. Because my relationship with him is not through a résumé, it’s through these decades of making things together.

Is it easier to work on the third movie of the series as opposed to the first one? On the one hand, you have a template in place; on the other, you have to keep things fresh and keep topping yourself.

Nathan Johnson: For me, this one was trickier. The thing that I eternally love about Rian’s approach to making a movie is that we don’t consider these sequels, and we don’t think of it as a franchise. Each one really has to have its own reason for being. To my great pleasure, when I read one of the new scripts, it’s tonally and structurally completely different. That carries through all the elements of the movie, obviously, from a completely different cast to totally different approaches across all the crafts as well.

Musically speaking, for the first Knives Out, there was a string quartet in this claustrophobic mansion.

For Glass Onion, we referenced these romantic, ’70s-era lush orchestral scores and went to Greece.

For this one, Rian was really excited about going gothic and darker, which you can hear in “A Minor Omission.” A big part of it was tapping into this underlying dread, as well as the tension and beauty that is expressed in this movie.

Listen to an exclusive track, “A Minor Omission,” from the Wake Up Dead Man score:

Nathan, your recording process is unique, from tuning wine glasses to using industrial material. It reminded me of The Brutalist composer, Daniel Blumberg, who previously told me about recording in a quarry for an echo he was looking for. What was your recording process for this one?

Nathan: My doorway into it was using an orchestra, but misusing it to try to subvert what that usually sounds like. For instance, one of the main percussive elements in the movie is a bunch of bass clarinets, using their keys in a sort of cascading, laggy, imperfect sound.

Are you talking about the horror-like motif in the score that sounds like spiders walking, for lack of a better comparison?

Nathan: Yeah, it’s like spiders crossed with falling dominoes. We recorded that in a giant old stone church in London. So these are fun things, but the story defines them. It’s an entire string section scraping their bows, like nails on a chalkboard, to produce an uncomfortable, ugly sound that resolves into a single pure tone. It’s a straightforward concept, but it really captures the heart of the movie — the tug-of-war between darkness and light, or between ugliness and beauty.

How did you first develop such an adventurous process?

Nathan: Part of it is probably inherent to both our musical tastes. We really like imperfection, and we tend to shy away from overly polished things. This DNA traces back to Brick, a movie set in a modern high school. In Rian’s mind, all high schoolers are listening to Tom Waits, and that was sort of the compass we took for that. There were also very practical constraints due to limited funds. So instead of a whole string section, I thought maybe an interesting way to [achieve that sound] was with tuned wine glasses, which have a similar, yet slightly off-kilter sound. Instead of timbales, we were hammering mallets on a filing cabinet in my hallway. I’m really compelled by the idea that sounds all around us make music, and all instruments started as non-official instruments.

Wake Up Dead Man straddles the line between a sweet earnestness and abject horror, both modern and gothic. How do you go about striking all of those very different tones? Is that all the script, or are you fine-tuning up until when you’re editing the picture?

Rian: I wish I were smart enough to do that calculated tuning. The reality is, I think it’s just instinctual. A lot of it happens in the writing phase. I don’t play music the way Nathan does, but it’s kind of probably like improvising. You’re just feeling the balance of what you’re describing as you go. In general, my approach is that as long as all of those different tones that you described feel truthful in terms of the characters and serve the needs of the story in that particular beat of that specific scene, that’s the trick to make them feel organic. If there’s a beat with a laugh, it’s a laugh that reveals character or advances the story. If it’s all pulling in the same direction, then it’s gonna feel totally coherent.

Rian, what’s it like when you get Nathan’s score back? He goes into this church, and he’s hitting wine glasses — it must be interesting to first listen to the result of his work.

Rian: On one hand, it is a very organic process, the way that we work, since Nathan is on set while we’re shooting, which I think is kind of unusual. But also, he’ll take a run at something, and I play it, and it’s this magical thing of the alchemy of, “Oh my God, this just completely upped the game of this entire sequence.” That’s part of what I love about working with Nathan. It’s not like a magic box that spits something out. It’s a collaboration from the very start, one hundred percent.

Nathan: The thing that’s so nice about that is this other world where you go away, record it, and come back — that’s just never the way we work to the degree where I’m sending Rian voice memos or playing little rough things on set, and then I get to see his reactions to those.

To me, that intensely collaborative process makes total sense: crafting both the scenes and the music in tandem, rather than recording them completely separately after everything’s been shot and edited. Would you agree?

Rian: Look, to be fair, what you just described is the way John Williams works. So there can be great, beautiful music made that way. I think for us, this is the way we do it. It works for us.

Rian, how did you go about writing this story?

Rian: I start looking at the movie’s basic, fundamental, dramatic line, which, in a whodunit, is usually not the murderer’s identity. It’s actually the same questions as any other movie: Who is the protagonist? What do they want? Why can’t they get it? How do they get it in a way they don’t expect at the end? That’s kind of the only thing that you can really strap yourself to, and that’s going to carry you through to entertaining an audience in the dark for two hours. I then start zooming in and figuring out how to get from here to there in terms of the whole arc.

So you know the beginning and the ending right off the bat, and work from there?

Rian: Yeah, I do, but the beginning and the ending in the context of the story as opposed to the plot. When it comes to the mechanics of the mystery and how it’s resolved, sometimes that won’t come till much, much later.

Do you ever change your mind about who the murderer is in these movies?

Rian: Never, but for an interesting reason. Readers, skip over this part if you want, but you can actually solve 90 percent of Agatha Christie books or mysteries knowing this little trick. Nine times out of 10, the murderer at the end is not going to be the least likely suspect, but the character who would be the most dramatically satisfying in the story so far. It’s not like you have a group of suspects and any one of them could have done it, and you kind of randomly pick one and surprise people. The whole thing is built, hopefully, with a dramatic spine, where it’s satisfying in the end that that person has been baked into the story from the start.

Well, for what it’s worth, I definitely couldn’t guess with this particular story. I didn’t have the faintest clue, actually.

Rian: Having said that, I can never guess these things either.

Nathan: One of the lovely things about, specifically, this movie, is I feel like I would enjoy it just as much if I knew who did it before seeing it. It’s also why I think we love rewatching these. The whole movie isn’t built around a reveal, but upon emotional connection and catharsis. As a composer, that is very rewarding because that means my job is to help tell the emotional story, which is how any good movie should work.

Rian, I wanted to ask you about one hilarious line: A character says they’re afraid Netflix would make a movie about this story and boil everyone down to one-dimensional characters. It was the biggest laugh at my screening. Why did you decide to include that?

Rian: It’s a little bit cheeky, obviously. But also, I was always looking for ways to bring the audience back to the fact that this is happening in the present moment. So there are pop culture references, like the Netflix joke or a Star Wars joke. It serves as a function of, we’re not in the 1930s here. They feel like things the characters would actually reference.