When the Bernsteins Hosted the Black Panthers

'Maestro' skips a key chapter in their life, resurrected in a new documentary about nemesis Tom Wolfe

Aside from that prosthetic nose that Bradley Cooper dons to portray Leonard Bernstein in Netflix’s Maestro, the biggest questions surrounding the film in advance of its world premiere at the Venice International Film Festival were exactly what parts of Bernstein’s prodigious career, which took him from concert halls to Hollywood to Broadway, would make it into the two-hour-nine-minute film. Because certainly there wouldn’t be room for everything. Once the movie unspooled and was met with a prolonged standing ovation — seven minutes? 10 minutes? Reports varied — the answers came into focus.

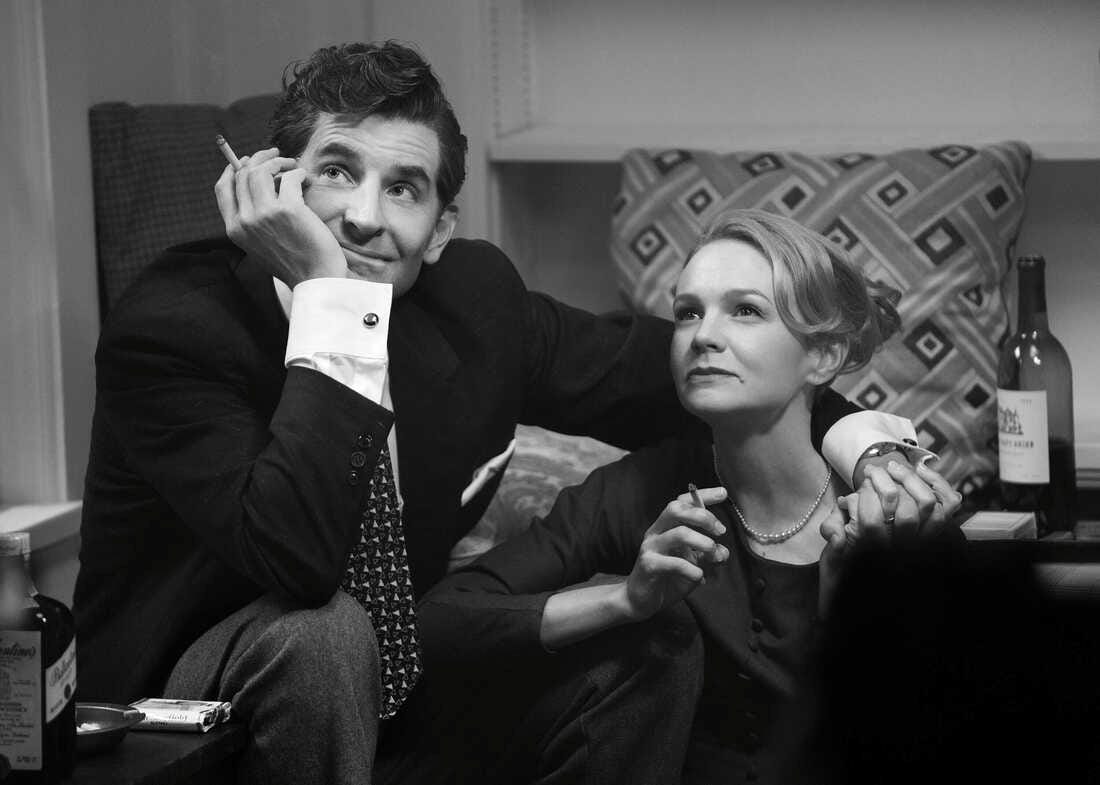

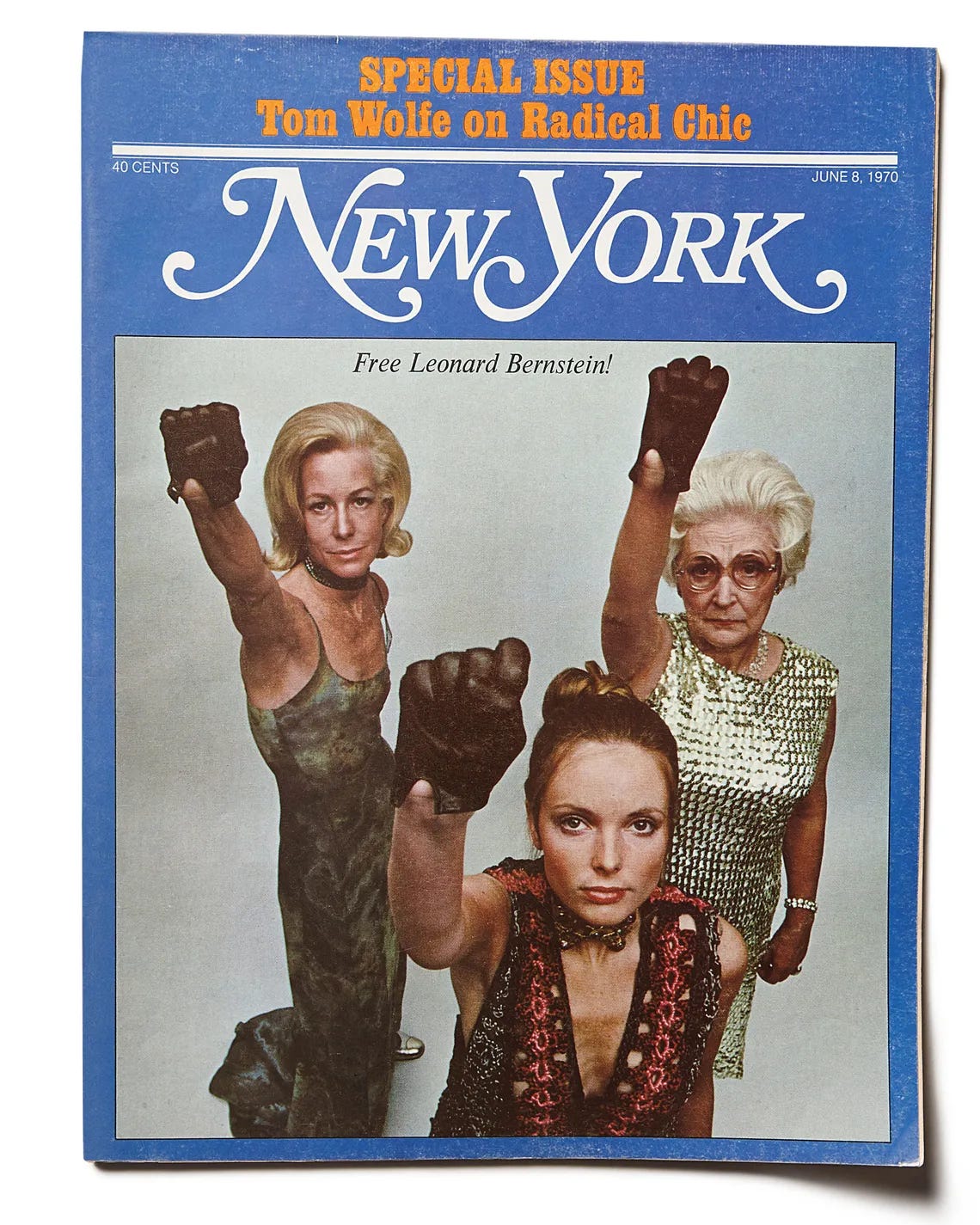

Maestro, which Cooper also cowrote, directed and produced, centers on Bernstein’s complicated but ultimately loving 27-year marriage to Felicia Montealegre, played by Carey Mulligan. There are brief interludes devoted to the male affairs Bernstein enjoyed on the side; brief walk-ons by his contemporaries like composer Aaron Copland, choreographer Jerome Robbins and his On the Town collaborators Betty Comden and Adolph Green, and passing references and musical quotes from Candide and West Side Story. But, as more than one reviewer was quick to point out, the film studiously avoids any mention of journalist Tom Wolfe and his 25,000-word 1970 New York magazine article, “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s”, which coined a new phrase at the Bernsteins’ chagrinned expense.

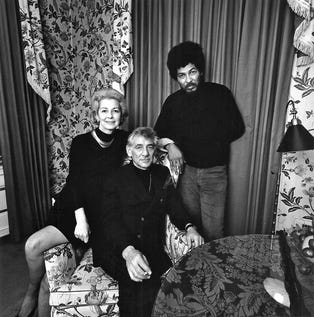

Wolfe’s piece, which would become one the most legendary examples of what at the time had been dubbed the New Journalism, arrived like an impudent thunder-clap, outraging New York’s social elite and delighting many in the media. It revolved around a swanky cocktail party that the Bernsteins held in their Park Avenue penthouse in support of the Black Panthers, the militant Black Power-preaching organization founded a few years earlier by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton. As portrayed by Wolfe, the Bernsteins — and the rest of the glittering gathering which included Mike Nichols, band leader Peter Duchin and Barbara Walters, among others — came across as privileged and pampered liberals thrilled to be in the company of genuine revolutionaries as uniformed maids pass around trays of “little Roquefort cheese morsels rolled in crushed nuts. Very tasty. Very subtle. It’s the way the dry sackiness of the nuts tiptoes up against the dour savor of the cheese that is so nice, so subtle. Wonder what the Black Panthers eat here on the hors d’oeuvre trail? Do the Panthers like little Roquefort cheese morsels wrapped in crushed nuts this way, and asparagus tips in mayonnaise dabs…”

Wolfe didn’t limit himself to lampooning only the Bernsteins and their guests. He went on to make sport of other bold-face names supporting various causes as the tumultuous ‘60s drew to the close. And he drew parallels to other periods in New York’s history: in one tangent he recounts the 19th century rivalry between the old money’s Academy of Music and the new money’s Metropolitan Opera, which also just happens to be the peg on which the just-completed season of HBO’s The Gilded Age hangs.

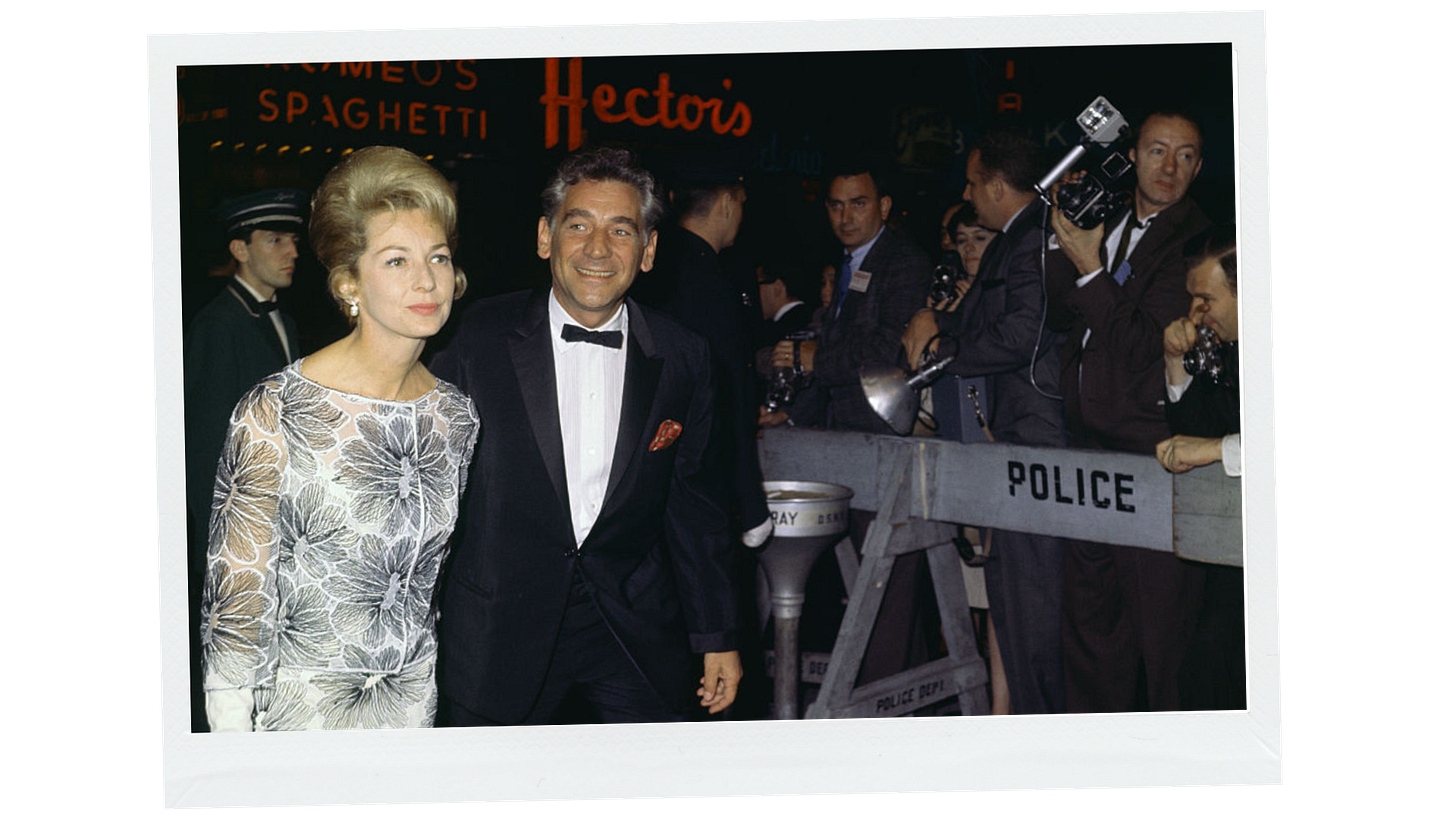

But Wolfe kept circling back, almost obsessively, to the Bernsteins, offering up vivid descriptions which, as it turns out, sync up quite closely with Cooper and Mulligan’s portrayals in Maestro. Of Bernstein he wrote, “Lenny is a short, trim man, and yet he always seems tall. It is his head. He has a noble head, with a face that is at once sensitive and rugged, and a full stand of iron-gray hair, with sideburns, all set off nicely by the Chinese yellow of the room. His success radiates from his eyes and his smile with a charm that illustrates Lord Jersey’s adage that ‘contrary to what the Methodists tell us, money and success are good for the soul.’” And of his wife, Wolfe adds, “Felicia is remarkable. She is beautiful, with that rare burnished beauty that lasts through the years. Her hair is pale blond and set just so. She has a voice that is ‘theatrical,’ to use a term from her youth.”

Although Wolfe’s account would stand as the definitive version of events, he wasn’t the only skunk at this particular garden party. Also present was Charlotte Curtis, then editor of the New York Times style section, who quickly published her own story about the event. That, in turn, led to a Times editorial, which lectured, “the group therapy plus fund-raising soiree at the home of Leonard Bernstein, as reported in this newspaper yesterday, represents the sort of elegant slumming that degrades patrons and patronized alike. It might be dismissed as guilt-relieving fun spiked with social consciousness, except for its impact on those blacks and whites seriously working for complete equality and social justice. It mocked the memory of Martin Luther King Jr., whose birthday was solemnly observed throughout the nation yesterday.”

Given such a notorious chapter in the Bernsteins’ life, which saw Leonard first rise to his wife’s defense once she became the subject of ridicule and then attempt to put distance between themselves and the Panthers, some wondered why Cooper chose not to include it in his film. It would seem to be dramatic catnip.

Cooper admitted in an interview with David Remnick, present-day editor of the New Yorker — back in the day, the New Yorker had also been another of Wolfe’s satirical targets — that he did seriously consider including the incident. But, he explained, “The spine of the film was always going to be [Lenny and Felicia’s] relationship. And the thing that was so clear was that there could be only one villain. I didn’t want to have another outside incident that brings them together. The villain is part of Lenny. He’s the villain. He’s the thing that I wanted to focus on breaking up their marriage, or the caustic element of this dynamic. It really diluted his accountability for her state to introduce [the Black Panther benefit] into this narrative. And that’s why I ultimately took it out. If you add in another villain, Tom Wolfe sitting there, it’s not as strong.”

Fortunately for those viewers who feel Wolfe’s absence, there’s a new documentary, Radical Wolfe, that also just arrived on Netflix, which almost serves as something of a companion piece to Maestro. Richard Dewey’s film, written by journalist Michael Lewis, is a largely laudatory account of Wolfe’s singular life and career. But in the section devoted to Radical Chic, it doesn’t let the perennially white-suited Wolfe get off scot-free.

In the doc, Wolfe himself explains how he crashed the party. Spotting an invitation on the desk of fellow journalist David Halberstam, he simply jotted down the RSVP number and responded in his own name. As for the fall-out, he insists, it was not his job as a writer to worry about what effects his words would have.

But Lewis himself raises the question “whether he crossed the line in that story into, you know, cruelty.” And the doc offers up a couple of possible answers.

Jamal Joseph, a former Panther turned professor at Columbia University, says of Wolfe’s piece, “It kind of put a derisive label on the good work that was happening, and it wasn’t good work just because people were contributing money. It was good work because consciousness was raised around injustices that were happening in our society. And I think that article was trivializing what we were doing and the Bernstein family felt this betrayal.” Testifies Bernstein’s daughter Jamie, “He didn’t give us a thought as to how his words might be hurtful to the people he was making fun of.”

So while Wolfe’s fans may feel Maestro missed an opportunity for a comic set-piece, Bernstein devotees are sure to applaud Cooper for the choices he made. For by in effect silencing Wolfe, he finally gave the Bernsteins the last word.