TV Producers' Delicious Dream of Fin-Syn's Return, One Step Closer

Many are rallying for Jon Voight's call to revive 1970s rules on show ownership, a chance finally for indie studios to compete

I write about TV development from L.A. I recently interviewed Mara Brock Akil about her hit Netflix series Forever and surveyed writers about whether the WGA strike was worth it. Email me at lesley.goldberg@theankler.com

In 2017, before Shonda Rhimes upended the television industry with her shocking move from Disney to Netflix, there was a period when I thought the mega-producer behind Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal was going to take her prolific Shondaland banner independent. Such a move would have given the mistress of the Bridgerton universe and The Residence executive producer full ownership of anything she made — series, films, live events, etc.

By signing to a big overall with Netflix instead, that ownership went to the streaming giant, with Rhimes receiving rich upfront payments and bonuses for getting and keeping shows on the air. Netflix, in signing Rhimes (and extending her deal through 2026), ushered in an era of streamers looking to own more of their programming in perpetuity.

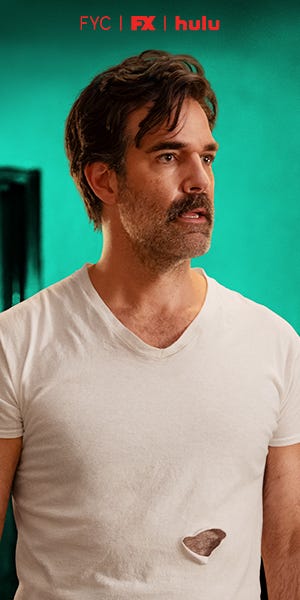

Now, Oscar winner Jon Voight wants to reinstate the Financial Interest and Syndication Rules (aka “fin-syn”), first imposed by the FCC in 1970, that would prevent streamers and broadcast networks alike from owning all of their programming. It’s one of the most intriguing, if unlikely, parts of Voight’s pitch to President Trump to “make Hollywood great again.”

“Fin-syn came about because President Nixon hated the broadcast networks because of the news — does this sound familiar?! — but on the other side of the coin, the broadcast networks wanted control of their schedules . . . and didn’t want to give up their foothold,” says one longtime studio and network executive.

Nixon and the FCC established fin-syn rules in 1970 to prevent ABC, CBS and NBC from monopolizing prime time. A separate FCC regulation at the time also required the then-Big 3 broadcasters to give an hour of their prime time schedule to local stations and independent producers (called the Prime Time Access Rule), an attempt to encourage competition and also limit their influence.

The fin-syn rules were abolished in 1993 in a move to help U.S. networks compete with global players amid the explosion of cable networks (which weren’t subject to fin-syn) and as Fox made broadcast’s Big 3 into the Big 4. The repeal opened the door for networks to vertically integrate with their own studios, creating the current landscape in which streamers and networks alike own the bulk of their programming. By owning their content, outlets can limit soaring licensing fees and have more control over shows while also keeping them within their own walled gardens.

Law & Order captain Dick Wolf, for example, has been based at Universal Television for nearly four decades, and he’s behind five of NBC’s seven scripted shows — though he also has two that air on CBS that are co-productions with Paramount. Speaking of CBS, of the network’s scripted shows, only two come from outside studios, with two others co-owned by parent company Paramount, with 16 (including NCIS, a long-running global hit, and newcomer Fire Country) owned by CBS. On streaming, once Rhimes went to Netflix, other streamers followed suit with a wave of rich overall deals designed to keep top showrunners exclusive to a single platform, though we’re seeing fewer of those overalls these days, and even first-look deals are changing as Elaine reported.

We’ve been in a post-fin-syn world for more than 30 years now, and if fin-syn rules were to return — and that’s a big if — it would upend the current economics of the entire industry and force broadcast networks and streamers alike to buy programming from outside their walled gardens. Such a move, multiple industry insiders tell me, could be a boon for independent studios who, without IP ownership, now have a harder time getting a show on the air. (Reminder to read Elaine’s interview with MRC’s Jenna Santoianni to see how the smaller players now compete.)

Before I dive in further, a quick programming note: I will be moderating panels with Liz Garbus (Good American Family) and Alethea Jones (High Potential) on Sunday as part of The Ankler and Directors Guild of America’s “The Art of the ‘Show’: Demystifying TV Directing” at the DGA Theater, where my colleagues Elaine Low and Katey Rich will be leading conversations with Yana Gorskaya (What We Do in the Shadows) and Jessica Lee Gagné (Severance) as well as DGA president Lesli Linka Glatter (Zero Day), Lucia Aniello (Hacks) and Damian Marcano and Amanda Marsalis (The Pitt). You can request to attend here, and if you’ve got a question for us to ask one of these top helmers, sound off on Threads!

Now, back to today’s main event. I spoke to network insiders, a top writer and an attorney with some skin in the game to understand what’s behind Voight’s fin-syn push, whether it could possibly happen and the fallout if it does. You’ll learn:

How quickly a return to fin-syn could happen under the Trump administration

How a return to fin-syn would affect megaproducers like Rhimes and Wolf, and what it could mean for all writers

The exec jobs that could come back to Hollywood under a new fin-syn-type structure

The existential risk for the broadcast networks

One top showrunner’s concerns, despite the potential financial upside

Why one top entertainment attorney has been pushing for a fin-syn update long before Voight’s move

How a modernized fin-syn could benefit “entrepreneurial” creators and producers

What Voight did right