The Man Who Built ‘Marty Supreme’ (and Won Over Chalamet)

Jack Fisk is ‘the finest production designer on the planet,’ the star said. I talk to the legend about a career working with Iñárritu, de Palma, Lynch & Malick

Today, I’ll get right down to it: I’ve got a conversation with production designer Jack Fisk, an absolute legend who stands a chance of winning his first Oscar this year, even though he probably should have won at least three times by now. You don’t have to take my word for it: The American Cinematheque just announced a weeklong retrospective of his work, which ranges from 1972’s landmark Badlands to his latest, Marty Supreme. Even better? He’s one of the nicest people I’ve ever interviewed, the kind of conversation so good it went on way longer after I turned off my recorder.

But first, a few programming notes: Prestige Junkie After Party is going strong with an extremely fun, extremely nerdy episode coming up this Friday with returning guest David Canfield (subscribe here to listen), and the regular Prestige Junkie podcast feed is keeping busy as well, with another bonus episode coming this Saturday with Ethan Hawke. I’ll break down this Sunday’s BAFTA Awards on the podcast next week, but if you can’t wait that long, join me and Christopher Rosen on Substack Live and The Ankler’s YouTube page this Sunday evening at 6 p.m. PT, where we’ll go over all the highlights of the Alan Cumming-hosted show. See you there!

Jack of All Trades

Jack Fisk is grateful for the attention Marty Supreme star Timothée Chalamet has given him throughout their awards-season run. The 79-year-old production designer was the revered elder statesman on the set of Marty Supreme, bringing his career’s worth of experience working with the likes of Terrence Malick, Martin Scorsese and Paul Thomas Anderson to recreate the streets of 1950s New York.

Production designers rarely get draped in the kind of glory that Chalamet and director Josh Safdie have been giving Fisk on this press tour (“He’s probably the finest production designer on the planet,” Chalamet said during a January event). Still, Fisk has warned his young star that there may be unintended consequences. As he told me in a conversation in Los Angeles last week, the last time an actor talked about Fisk so much in the press, he married her.

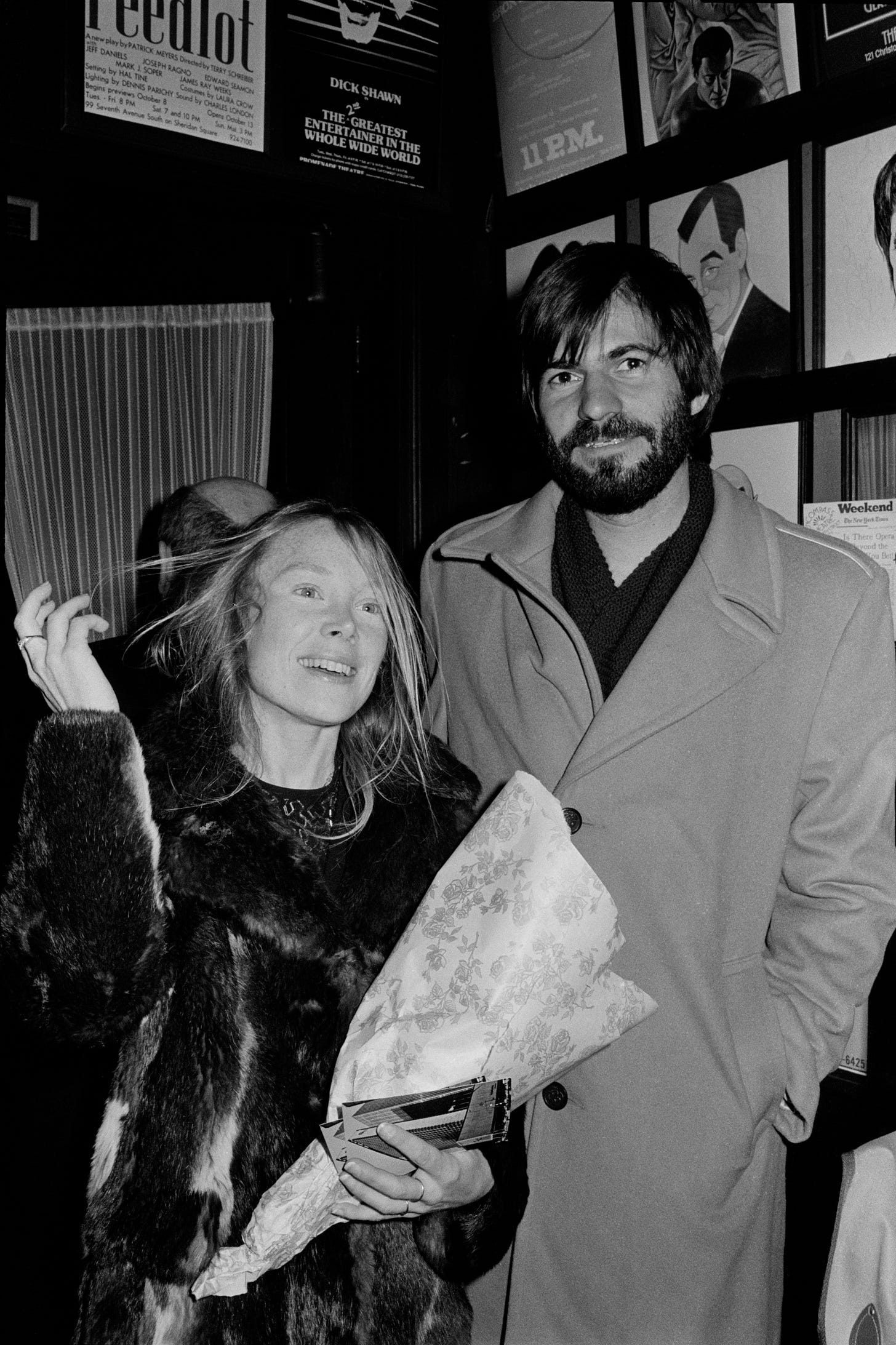

He’s probably right — Fisk met Sissy Spacek on the set of Malick’s Badlands in 1972, one of the first films either had worked on. They married in 1974 and have two daughters and a passel of grandchildren who all live nearby on Fisk and Spacek’s rural Virginia farm. It sounds like a pretty ideal retirement for anyone, but neither Fisk nor Spacek — who gave phenomenal performances in both the miniseries Dying for Sex and Lynne Ramsay’s Die My Love just last year — seems interested in basking in familial solitude.

As Fisk put it to me, “If I’m not working on a film, I get lazy. Even though I have a woodshop and a lot of stuff to do, I don’t have that stress, the tension, saving the day.” On a set, he continues, “You feel like Mighty Mouse.”

One of the first collaborators for Malick, David Lynch (Eraserhead) and Brian de Palma (Carrie) as they started their careers, Fisk has done more to capture the American experience than most. He’s the builder of the surreal version of Los Angeles in Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, the pre-colonial America of Malick’s The New World and the stark Western vistas of Anderson’s There Will Be Blood; he’s the person Alejandro González Iñárritu asked to build an entire frontier fort in the actual wilderness for The Revenant, and who recreated an Oklahoma boom town for Scorsese in Killers of the Flower Moon. It’s a career working with titans that has led to four Oscar nominations (There Will Be Blood, The Revenant, Killers of the Flower Moon and Marty Supreme), but without any wins thus far. No wonder Chalamet can’t stop talking about him.

Maybe it’s been too easy for Oscar voters to overlook Fisk’s work because it’s so precise and fully realized that these sets feel like they’re plucked from the actual past. Take what he did with Marty Supreme: Fisk not only recreated the Lower East Side streetscapes of the 1950s, but also depicted the tenement apartments where characters like Marty Mauser — Chalamet’s born hustler and ping-pong prodigy — live alongside multiple generations of their families. People still live in many of those old apartment buildings, but Fisk may be the only person who sounds disdainful when he talks about the safety improvements made in the last century.

“Nowadays they have modern windows, they have steel fire doors and fluorescent lighting and everything,” Fisk tells me. “I thought it was important to harken back to the ’50s and before, when families would move in there and work to survive and make a name for themselves.”

If Fisk and his team had to build a staircase in Marty Supreme, they made sure the steps were worn down where generations of people would have walked. The windows are dirty, the railings look like they’ve been painted over 10 or 20 times — because they probably have been. “If you don’t do that, it just looks like a stage set,” he tells me.

Films, Fisk tells me, have a transportative effect. “You can spend some time in different eras, and it’s like you get to know the people there,” he says. “It’s better than a history book.”

Building Blocks

When Fisk graduated from Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1970, there was a pretty clear path laid out for his future as an artist. “It’s the rest of your life in a studio painting or building by yourself,” as he puts it. Instead, Fisk followed his friend Lynch to California and found a job with the late indie-film pioneer Roger Corman, whose track record of giving major talents their first breaks is legendary.

Fisk didn’t even know what an art department was, but he was suddenly running one — or on those earliest films, he was the entire art department. Instead of painting alone in an artist’s studio, “I thought, ‘This is so much fun working with all these people putting together a project.’” He continues, “When you’re 20 years old, and you’re looking at a canvas and thinking, ‘What important thing do I have to say?’ I found that having the script’s guidance was really helpful. It was also fun to be working with other people, so I wasn’t in there by myself.”

The boundless energy required by those famously shoestring Corman sets has continued throughout Fisk’s career, and he seems to particularly jibe with directors — Anderson, Scorsese and now Safdie — who can match his level of enthusiasm.

“Paul is always funny,” Fisk says, explaining how he helped Anderson scout locations for One Battle After Another even though he didn’t ultimately work on the film. “He’s like a little kid in his enthusiasm. He’s an American treasure. He’s probably our best young filmmaker — well, Josh is nipping at his heels.”

While working on Marty Supreme with Safdie, Fisk says he often called the 41-year-old director “Paul” by mistake. “He’s got the energy and the excitement. I always look for a director with a lot of passion and a challenging project. I like to have a project that scares me a little bit.”

Fisk considers it his job to never shoot down a director on a set and to always answer texts no matter what — even if they come in after midnight, as was the case with Safdie. (“I don’t want him to think I sleep,” Fisk says of the filmmaker.) Still, there was one part of Marty Supreme that required him to say no.

“He asked me to paint Marty’s room white, and I said, ‘I can’t do that.’”

His reasons were based in history — “rooms in the tenement weren’t white, and it was the one chance that people had to put some color in their lives” — but also the logistics of cinematography, learned from years of collaborating with cinematographers like Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki. When Lubezki and Fisk worked on films like Malick’s The Tree of Life or Iñárritu’s The Revenant, they never used whites. “It looks like it burns a hole in the film,” he explains. “People look much better on dark backgrounds. It has just been ingrained in me to stay away from white.”

In the final film, Marty Mauser’s bedroom is tiny and crammed with ping-pong trophies — and the walls are green.

My long, rambling conversation with Fisk is basically the opposite of the frenetic, chest-puffing energy of Marty Supreme — we got into Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl performance (“He’s such a nice guy”), Fisk’s daughter’s dog, the time he got lost in the woods while scouting locations for The Revenant and what he’s learned about railroad workers in the Old West as he preps for his next film, with Ang Lee.

But it’s also clear that he’s a kindred spirit with Marty Mauser, Safdie and Chalamet. Fisk says when he first met the star, Chalamet dropped to the floor and did 10 push-ups.

“I was talking to Timothée about it,” Fisk tells me. “I said, ‘Timothée, I think there is a little Marty in all of us.’ He says, ‘I think there’s a lot of Marty in all of us.’ He feels that way about acting. Josh feels that way about filmmaking. I feel that way about building things. For me, building these worlds that help the actors and help tell the story and propel the story is my favorite thing to do.”