The 'Grey's Anatomy' Liar Confesses it All

Elisabeth Finch, disgraced and in exile, explains what made her do it

“At a certain point, the hardest thing becomes remembering what you said or told people.”

It’s Halloween, a fitting holiday for former Grey’s Anatomy star writer Elisabeth Finch to sit for her first of four interviews since her mask was ripped off seven months earlier. She is seated in a wooden lounge chair so old and rickety that it’s threatening to collapse, perched high above Los Angeles’ Topanga Canyon on a slatted wooden deck that overlooks her sprawling hillside property. She’s wearing a white embroidered dress, a purple shawl and a blanket draped over her lap to stave off the afternoon chill. She looks nervous but appears determined to work her way towards a full confession. “When you get wrapped up in a lie you forget who you told — what you said to this person and whether this person knows that thing — and that’s the world where you can get caught,” she says in a voice that starts to quaver. “I don’t have to worry about that now.”

In March, Finch’s grandiose ruse, which included a head-spinning web of deceptions that started with a fabricated debilitating cancer diagnosis, abortion and kidney loss stretching back nearly a decade, was first made public in a story by The Ankler after Disney (whose ABC broadcasts Grey’s Anatomy) and production company Shondaland had put one of their best-known writers, now 44, on leave. Even in an industry famous for celebrating and accepting fabulists, charlatans and con artists, the nature and extent of Finch’s lies crossed an unspoken line. No, she hadn’t physically hurt anyone like, say, Harvey Weinstein or Kevin Spacey. But Finch, by fabricating and dramatizing huge swaths of her life story, broke the trust of one of the most successful writers’ rooms in Hollywood history — and made fools of Shonda Rhimes, the town’s most powerful TV producer, and Disney, the most family-friendly maker and distributor of TV in the world.

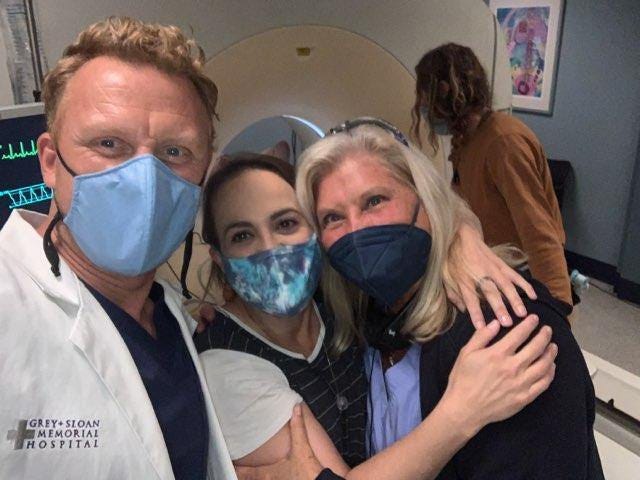

Of her time at Grey’s, days where she taped a dummy catheter to her arm and shaved her hair to feign that she was undergoing chemotherapy, she now says, “I really miss it. I miss my fellow writers. It's like a family and… one of the things that makes it so hard is that they did rally around a false narrative that I gave.”

Today? She’s an absolute pariah. The mere mention of her name in certain quarters of the industry causes visible revulsion. Her phone doesn’t ring. Her emails go unanswered. Her wife left her, family members disowned her and she’s no longer allowed to see the children she helped rear for several years. She fills her day taking long walks and talking to her therapist. And she’s sitting down with me, the reporter who first broke the story about her lies, to tell her story. This time, she says, a real one. Because there is nothing else she can do.

“What I did was wrong,” she says. “ Not okay. Fucked up. All the words.”

Getting Caught

Finch’s story is uniquely Hollywood: celebrities, melodrama, a wild and bitter divorce. But she is also a product of this New Age of the Modern Grifter, captured and immortalized on screen now in our collective imagination: Theranos’ Elizabeth Holmes (The Dropout); Anna Delvey (Inventing Anna); Adam Neumann (WeCrashed); and now Sam Bankman-Fried, whose staggering $32 billion crypto meltdown is the subject of multiple pitch meetings right now. And lest we forget OG Bernie Madoff was played onscreen by not one but two Academy Award-winning actors: Richard Dreyfuss and Robert De Niro.

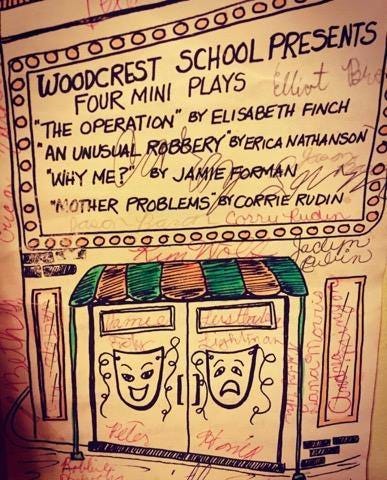

In the limited miniseries of Finch’s life, you would start with establishing shots in leafy suburban New Jersey. The first episode would open on an awkward but precocious teenager tapping out her first plays. Writing, she tells me, saved her life and was her earliest form of therapy. Finch also loved watching TV (later, in her twenties, one of her favorite shows was Grey’s Anatomy, which first aired in 2005; she memorized character arcs and plot points in impressive detail).

The next episode would likely open with her finishing USC graduate film school and then track her early days struggling to break into the industry. We would watch as, through ambition and pluck, she works her way towards her first big job, writing for HBO’s True Blood, which ultimately leads to a staff job as a writer and co-producer on, yes, Grey’s Anatomy. In subsequent episodes, she becomes a star writer, credited with penning 13 episodes and producing a whopping 172.

Finch’s secret sauce? Her own life. Finch told colleagues that she had been diagnosed with a rare form of bone cancer called chondrosarcoma in 2012. Harrowing rounds of chemotherapy continued for two years after she was hired to be a writer on Grey’s Anatomy in 2014. But the cancer was just the beginning of her medical ordeal. She lost a kidney due to chemotherapy. Then part of her tibia was removed also on account of the cancer. She was forced to abort a fetus because chemotherapy made the pregnancy impossible. Through it all she endured, heroically, not only within the walls of the Grey’s writers’ room but outside of it. When she wasn’t writing for the show, she was busy penning essays for publications like Elle, The Hollywood Reporter and Shondaland, the website of Grey’s producer Rhimes. The essays read like story treatments, with brave and bold heroines (usually Finch and her female bosses) squaring off against clear villains (mostly men). It was a just matter of time before Rhimes incorporated elements of Finch’s life into the show, as reality and fiction started to blur. Dr. Catherine Avery, played by Debbie Allen, eventually assumed many of Finch’s own real-life struggles. “I wanted Catherine to be diagnosed with a spinal tumor similar to mine, only this time, the doctors would tell her the truth. Because she, like the rest of the world, shouldn’t have it any other way,” Finch wrote in an essay Elle published.

“We worked with someone who not only said she was sick with cancer but looked sick with cancer,” says one of her former Shondaland colleagues. She “regularly took breaks to vomit and only ate saltines for a period of time.”

Enter, then, an unlikely foil. Finch, who claims to have suffered physical abuse at the hands of her older brother as a child, checked herself into an Arizona facility that treats women who suffer from a range of disorders including trauma in the spring of 2019. There, she met a fellow survivor named Jennifer Beyer, who was escaping a broken marriage to an abusive husband. The two women fell in love and married. But Beyer, a registered nurse, was not just a supporting character. Through some clever sleuthing, she uncovered the truth about her new wife, confronted her, and demanded that she come clean to friends and family. At first, Finch reluctantly began confessing to a few close friends. But soon she bristled at Beyer’s demands for transparency and called an end to the confession tour. That was when Beyer took matters into her own hands. She contacted Shondaland and Disney, reaching out to Rhimes personally, to alert them that the stories Finch had been telling them, and the plotlines based on them, were born out of lies. From the clubby, cloistered, closed-lipped world of Shondaland, word that something had gone horribly wrong began to seep out.

On Finch’s 44th birthday this year, she received a call from a number she didn’t recognize. Thinking it was another well-wisher, she answered. It was a reporter calling to inform her that he was planning to publish a damaging story that challenged the central narrative that had helped build her career. The reporter, who had been trying to get in touch with her for days, wanted to give Finch a chance to tell her side of the story. Caught off guard, Finch hurriedly replied, “Now is not a real good time” and hung up.

For her birthday, she’d bought herself tickets to an off-Broadway show in New York called Suffs about the women's suffrage movement, and when the play commenced, she turned off her phone. While Finch watched, the story posted on The Ankler, including the fact that Disney was placing her on administrative leave while the company investigated Beyer’s allegations.

I know this because I was the reporter who called her and broke the story.

When Finch turned her phone back on and scrolled through her texts and emails, she realized life as she knew it was over.

“From that point on, I was cut off pretty quickly from everything,” she tells me. “I slowly started to see people blocking me on Instagram and other social media. It was so universal that I don’t know if an email went out or everyone just got together and decided ‘no thank you.’”

Her colleagues responded with shock, outrage and fear. “We worked with someone who not only said she was sick with cancer but looked sick with cancer,” one of her colleagues told me later. A co-worker “who lost her hair, whose skin was yellow and green, who had a visible chemo port bandage, who regularly took breaks to vomit, who only ate saltines for long periods of time and who wrote and talked about her experiences all the time.”

Finch resigned from the show before an investigation could begin and checked herself into an in-patient treatment at the same Arizona facility. This time, she stayed five weeks. Now, she rarely ventures out of Topanga. “I wish I had a grid that would show who’s not talking to me because they can’t [legally]. Who’s not talking to me because they don’t know what to say. Who’s not talking to me because they’re pissed off. And then who’s sitting there waiting for me to reach out. I have no clue.” She takes a breath. “It’s been a very quiet, very sad time. There were people who, when your article came out, were immediately very, very nasty on text. Family and friends who called me a monster and a fraud and said that’s all I’ll ever be known for and soon more truth would come out.”

“I’ve been gone bc my brother died by suicide,” she wrote in a note explaining an absence from Grey’s. “He was on life support for a short while but ultimately did not survive.” Her brother, Eric, a doctor, is very much alive and working today.

In early May, Vanity Fair published a long story about Finch without her cooperation, with a cover teaser that dubbed her “The Grey’s Anatomy Grifter.” The key source for the article was Beyer, the original whistleblower and Finch’s wife, whom she’s now in the process of divorcing. The Vanity Fair article painted Finch as a monster and Beyer — a victim of earlier domestic abuse — as her victim. After years of carefully spinning an elaborate backstory of fictionalized stories, she had lost control of her own narrative.

Several months after that story, I received a call from Finch’s lawyer asking if I’d be interested in interviewing his client (I’d requested the interview months earlier but figured I would have no shot). Considering the role I had played in exposing her, it was surprising. But I accepted: seven months after the story broke, I still had a whole host of questions. How was she able to deceive the most powerful people in entertainment? How did she get away with it for so long? And what could have motivated such wild inventions?

What made Elisabeth tick?

Since Halloween, I sat down with Finch on three other occasions and recorded close to five hours of interviews. Just the two of us, no lawyer or publicist present, and no ground rules on what I could ask.

From a reporter’s perspective, interviewing a serial fabulist presents all sorts of challenges. To begin with: how do you trust anything they say?

“I Lied and There’s No Excuse”

Our first meeting was at a café in Topanga Canyon for a preliminary off-the-record conversation. Unlike the brash and bold protagonist of her essays, the post-crash Finch is today meek and skittish in person. She dresses casually — in jeans and a sweatshirt on this occasion — and keeps her hair pulled back. I noticed quickly that it’s not easy to get into a conversational flow with her. She mixes drawn-out pauses with staccato-like interruptions and her eye contact is equally unpredictable. One moment she avoids looking at you, the next she’s staring intensely. At the crowded cafe, she was visibly nervous and as she sipped kombucha her eyes darted around to see whether we were being watched.

I told her that while I was willing to give her a fair hearing, I had no intention of writing a story that would help resuscitate her career. She nodded. As we began talking, it became clear that my concerns about her continuing to lie may have been exaggerated. Finch was ready to come clean. This was her “come to Jesus” moment.

“I told a lie when I was 34 years old and it was the biggest mistake of my life,” she said to me at a later meeting. “It just got bigger and bigger and bigger and got buried deeper and deeper inside me.”

Come on Elisabeth. I’m going to need to hear you say it.

“I’ve never had any form of cancer.”

That was a shocking admission. But others continued to spill out. Finch’s lies extended well beyond her medical history. After the 2018 terrorist attack on the Tree of Life Synagogue that killed 11 people in Pittsburgh, Finch claimed that she’d been a regular congregant there in college (she attended nearby Carnegie Mellon for her undergraduate degree) and that she’d lost a close friend in the shooting. She asked for time off from Grey’s to fly to Pittsburgh to help make burial arrangements for her deceased friend. She told people the FBI allowed her into the site to help collect the remains, as required by Jewish tradition. (The only true part was that, yes, while in college, she had attended a few services at the temple. She did not know any victims.)

Then came another doozy. In 2019, she told colleagues that her older brother, Eric, had committed suicide.

“I’ve been gone bc my brother died by suicide,” she wrote in a note explaining an absence from Grey’s writers’ room. “He was on life support for a short while but ultimately did not survive. I say this not because I need or want anything from anyone, I’m not a delicate flower or whatever, I just want people to know I’m still here, still part of the team,” she wrote.

In fact, her brother, Eric, is a doctor who currently works in Florida today.

“I know it’s absolutely wrong what I did,” she admits to me. “I lied and there’s no excuse for it. But there’s context for it. The best way I can explain it is when you experience a level of trauma a lot of people adopt a maladaptive coping mechanism. Some people drink to hide or forget things. Drug addicts try to alter their reality. Some people cut. I lied. That was my coping and my way to feel safe and seen and heard.”

During our first recorded interview, she lifts up the hem of her dress to expose a six-inch scar on her kneecap. This was, to borrow a screenwriting term, the inciting incident. During the 2007 Writers Guild strike, she injured herself while hiking in Temescal Canyon, which resulted in what she describes as years of medical purgatory. It took multiple surgeries for doctors to isolate her problem and she ended up having knee-replacement surgery. For months she was on crutches and grew dependent on friends (several of whom confirmed this part of her story). When she ultimately recovered, the lies started.

“What ended up happening is that everyone was so amazing and so wonderful leading up to all the surgeries,” she recalls. “They were so supportive. And then I got my knee replacement. It was one hell of a recovery period and then it was dead quiet because everyone naturally was like Yay! You’re healed,” she says. “But it was dead quiet. And I had no support and went back to my old maladaptive coping mechanism — I lied and made something up because I needed support and attention and that’s the way I went after it. That’s where that lie started — in that silence.”

In 2012, she started telling friends and colleagues that doctors had found a tumor encroaching on her spine. Complicated and unresponsive to chemotherapy, it was a rare form of cancer, she explained, that almost never afflicted anyone of her age. She tells me that she chose chondrosarcoma because it was a particular form of cancer that was difficult to treat. On February 26, 2014, Finch published the first of several cancer-related articles in Elle titled, “How Friends, Family, And Friday Night Lights Helped Me Fight Cancer. The essay begins: “I catch fragmented glimpses of my bald reflection in the elevator mirror as I go up, up, up — to a white-walled conference room, where a small herd of well-groomed doctors, all equally inscrutable, awaits.” It goes on to document how her colleagues sent inspirational messages — photos of friends and family holding up signs with the words “State” scrawled on them, a plot point borrowed from the hit show Friday Night Lights.

“It’s all very strange and tragic,” says TV writer Rick Cleveland, “and I haven’t come to terms with either the damage she’s done or the accusations she made against people…The whole thing is detestable.”

Unlike screenwriting, journalism is subject to a singular overriding ethos: everything you publish should be truthful and based on verifiable facts. By venturing out of the make-believe world of screenwriting into journalism, Finch set the stage for her unraveling. In one 2019 column for The Hollywood Reporter, she wrote, “Scientists around the world are finding new ways to keep people with metastatic cancer alive — not by curing it, but managing it long-term. (Think diabetics on insulin.) I am one of those people.” She went on to publish more articles at Elle, the subjects of which, over time, grew increasingly far-fetched.

In the same Elle essay as above, she shared an anecdote about a trip to Minnesota to attend an appointment at the famed Mayo Clinic. She referred affectionately to a friend named “Nick” who let her stay at his apartment near the clinic. The real-life friend is named Nick Buettner; he lives in Minnesota and is an expert on human longevity. When I asked Finch about Nick’s role, she said he drove her to the clinic and, while he waited for her in the parking lot, she would roam the hallways, wasting time to keep up the ruse. Several years ago, she says, Buettner and two other friends confronted her and asked if she was making things up. “Nick and his sister-in-law Kathy caught on and knew what was up. They approached me and said something didn’t seem right. I denied it,” she says. “I wish I hadn’t.” Buettner and his sister-in-law never told anyone else. “They were a second family that I lost.”

All of Finch’s essays have been taken down from the Elle website. The magazine has never issued an editorial note addressing one of the worst editorial scandals in its 77-year old magazine’s history. (The Hollywood Reporter has kept its two Finch columns, from 2018 and 2019, online.)

It wasn’t just an unhealthy craving for attention in the wake of her knee surgery. There was a second more sinister source of her trauma, she says. Finch grew up in the leafy suburb of Cherry Hill, in New Jersey, where she attended Cherry Hill High School East. Her parents were both educators and she had one sibling, an older brother, Eric, whom she claimed physically and emotionally abused her for most of her childhood.

“It wasn't just casual sibling rivalry stuff,” she alleges in our interviews. “There were two things going on: one, my brother was abusing me, and two, my parents weren't listening. A lot of scientists, psychologists, psychiatrists will tell you that the negation of [abuse], or not hearing it, can sometimes be an even bigger trauma than the original trauma itself.”

I ask if she’d ever been hospitalized with broken bones or if there were any medical records of the abuse.

“Eric was very.…” She pauses. “Even saying his name is hard.” She collects herself. “He was very good at doing things that were terrorizing and physical, but not enough to leave marks. That's one of the threads that I went through — where's my evidence? Prove it. Where’s the document? Where’s the scar? Where's the whatever? As I grew into adulthood I didn't have [evidence],” she says.

Multiple emails to Finch’s parents and brother seeking comment were not returned.

Finch is adamant that her compulsive lying was solely a product of her real-life trauma. The allegations of childhood beatings from her brother, triggered later in life by the silence and loneliness that came after her knee replacement surgery at age 34. “I didn't know the connective tissue between my brother and my medical trauma and my depression and PTSD and anxiety,” she says. She’s sat with multiple therapists, she tells me, and pored over the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the handbook and authoritative guide to mental disorders. The message from her therapists was unanimous: it’s not a personality disorder, it’s trauma.

I was skeptical, so I reached out to an expert

“This sounds like a classic case of factitious disorder,” says Dr. Marc D. Feldman, a professor of psychiatry and adjunct professor of psychology at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa and the author of Dying to be Ill: True Stories of Medical Deception. Factitious disorder only entered nomenclature starting around 1980 and awareness surrounding it has grown rapidly since then. According to Feldman, patients who exhibit its symptoms are overwhelmingly women and hard to identify because most of them live normal lives. The patients often work in the healthcare industry as a nurse or physical therapist or a clerk to gain access to medical information. Invariably, he says, they back themselves into a corner with a compounding of their lies over time and either have to come clean, claim that they’ve been cured or, in some extreme instances, claim divine intervention. Others just pick up and leave their communities and move on to their next marks.

“This case is typical in a lot of ways except it has the twist of being involved in the entertainment industry,” says Feldman (who has never met or treated Finch). “The main reason people seem to do this is that they have an underlying personality disorder or have a difficult time getting their needs met that aren’t self-defeating. Instead of asking for attention or care, they engage in pathological behaviors that allow them to get what they want indirectly.”

Finch owes a large debt to television writer Rick Cleveland. She got her start in the industry working as Cleveland’s assistant and he helped her land her job on True Blood. “I don’t believe she ever lied to me,” Cleveland said in an email to me, noting that Finch was helpful when his mother was in hospice with lung cancer. “It’s all very strange and tragic,” he wrote, “and I haven’t come to terms with either the damage she’s done or the accusations she made against people…The whole thing is detestable.”

One of the few old friends who reached out to Finch since she was exposed is a rabbi named Ben David. David and Finch grew up together and attended the same schools and summer camps. They weren’t close but David, like many people from Cherry Hill, kept tabs on Finch’s Hollywood ascent, which was the source of considerable hometown pride. Finch suggested that I reach out to get David’s perspective, as a rabbi and as a cancer survivor.

“It's not up to me to grant her easy redemption,” David tells me. “She did real damage to real human beings, people who trusted and loved her and she wounded them — some of them irreparably. She doesn’t get to wash her hands of any wrongdoing. Judaism believes in second chances and I choose to believe in second chances. But only after undergoing a real process of rehabilitation, self-assessment, a looking at the mirror that’s honest, profound and thorough.

“Will she do that?” David asks himself. “Unclear.”

A Culture of Fabulists

“The history of Hollywood is full of fiction as much off screen as on,” says Stephen Galloway, the dean of Chapman University's Dodge College of Film and Media Arts, who rattled off the names of several infamous scammers dating back to the silent-film era.

When Erich Oswald Stroheim arrived at Ellis Island in 1909, he was a penniless immigrant from Vienna. But he told immigration officials he was an aristocrat of noble origins named Erich Oswald Hans Carl Maria von Stroheim, an identity he brought to Hollywood which led to great success as an actor and director (he was Oscar-nominated for Sunset Boulevard).

“There’s a momentum that grows. Why do alcoholics keep drinking? Why do addicts keep using more and more?” she says. “I think it was a lie that got completely out of control and I got out of control with it.”

To lie in Hollywood, or at the very least to heavily embroider the truth, has been almost de rigueur. It’s no accident that the title of the memoir by producer Lynda Obst, considered required reading for anyone wanting to break into the industry, is: Hello, He Lied. One of the most famous examples of fibbing involves a 21-year-old Steven Spielberg, who claimed to have snuck onto the Universal Studios lot in formal business attire and set up an office in an empty bungalow. He says he convinced the gatekeeper to let him in each morning and the studio’s switchboard to set up an extension for him and put calls through. “Every day, for three months in a row, I walked through the gates dressed in a sincere black suit and carrying a briefcase,” Spielberg once told an interviewer. “I visited every set I could, got to know people, observed technique.” Or take the case of a young David Geffen who told one of his earliest employers, the William Morris agency, that he’d graduated from UCLA. He hadn’t. Worried that he might get caught, Geffen went into the office early for several months to intercept the university’s letter stating that he’d never attended. He successfully replaced the letter with one that said he’d graduated. He shared this origin story in an interview with Fortune, saying, “Did I have a problem with lying to get the job? None whatsoever.”

Indeed, Finch is only the latest in a long line of writers who embellished their life story, and let’s be honest — it was mostly men who did and many got away with it. James Frey wrote two bestsellers that were marketed as memoirs but he was later forced to admit that he’d fabricated large portions of both books. Despite the controversy, Frey continued writing books, one of which was made into a feature film, and he still has his own production company. Another writer, Augusten Burroughs, wrote a memoir called Running with Scissors that became a bestseller; later, he was sued for defamation by members of his foster family. The two sides ultimately settled in 2007 and part of the agreement required Burroughs and his publisher to call the work a “book” and not a “memoir.”

“This is a town that by its very nature draws people who imagine things,” Galloway says. Galloway argues that today, the internet, coupled with the corporatization and consolidation of the entertainment industry, has made these types of deceptions nearly impossible to pull off.

There were many moments when Finch might have pulled back from her con and gotten away with it. There’s an alternate version of history where Finch told colleagues that she’d been cured of her cancer and was ready to move on, or, hadn’t started publishing the personal essays that left a trail of evidence in perpetuity. Or if she hadn’t extended her lies to the Tree of Life synagogue or the “suicide” of her brother. Instead, she kept inventing new lies, some to cover her tracks, taking them as far as she could.

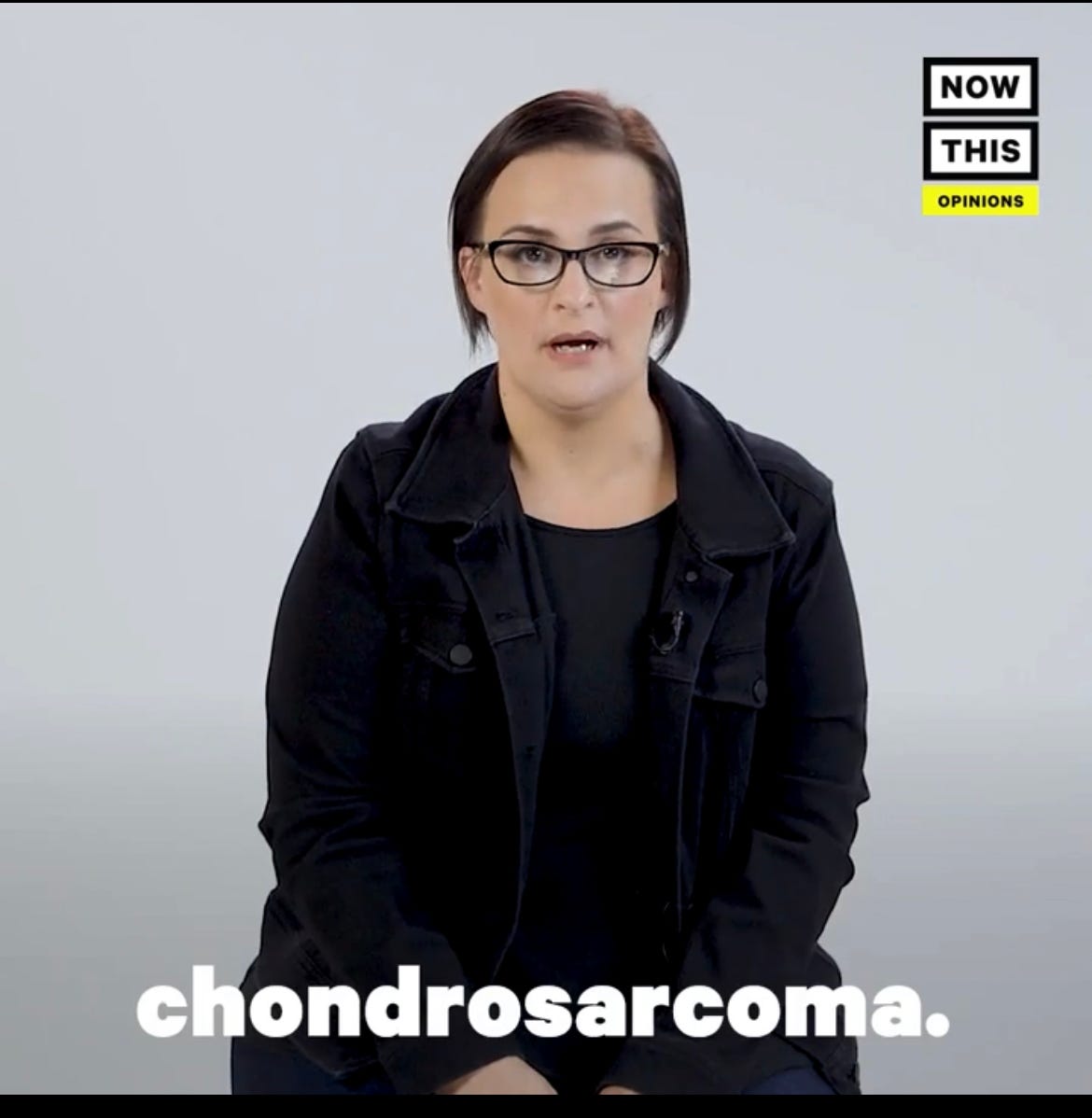

It wasn’t enough to tell people that she had to make a wrenching decision to abort the fetus from an unplanned pregnancy or risk her own life by forgoing the life-saving treatment. She weaponized it, taping a political campaign video during the explosive confirmation hearings of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh. “It wasn’t a decision I took lightly,” said Finch staring intently into the camera for NowThis. “But it was the right choice for me. The only choice for me. If Kavanaugh were on the Supreme Court when I got pregnant, what choice would I have had?”

At Shondaland, Finch would nibble saltines, the only food she said she could keep down. Her skin was pale and her head shaved but often cloaked in a scarf. The outline of the (fake) port catheter could be seen under her shirt and she would sometimes rush to the bathroom and feign retching.

“She always had some tragedy or bizarre hardship going on in her life,” remembers one colleague. “Things that don’t happen to other people happen to her all the time.” There was the time a Gulf War veteran had stalked her for months, slashing her tires and leaving a knife slammed in the front door of her apartment. Another time, she arrived at the office visibly upset. She’d been the victim of a road rage incident, she said, and after the male assailant caught up with her at a red light he exposed his genitalia and masturbated in front of her. Finch would often take to Facebook, Instagram and Twitter to share some of these harrowing events. Like the time an anti-Semitic flier was slipped under her front door. I ask her about these three stories and she claimed that all three actually happened. During her time on True Blood, she became close with actress and Oscar-winner Anna Paquin and her husband Stephen Moyer. One of the more extraordinary rumors that spread was that Paquin had donated one of her kidneys to replace the one Finch lost due to chemotherapy (I ask Finch about this rumor and she claims to have no clue how it started).

“There’s a momentum that grows. Why do alcoholics keep drinking? Why do addicts keep using more and more?” she says. “I think it was a lie that got completely out of control and I got out of control with it. I wasn’t some calculating puppet master trying to buck the system. I think it was something that got really freaking out of control and that’s what happens when you’re dealing with a maladaptive way of dealing with things. It just gets bigger.”

Inside Shondaland

Fred Einesman was growing concerned. The physician-turned-industry-consultant had been hired as an executive producer on Grey’s Anatomy in 2015. Einesman is part of a small cadre of real-life medical experts hired by medical shows to apply a level of verisimilitude to scripts that weave complex medical ideas into storylines.

Einesman’s concerns were twofold. He was both confused and skeptical of the stories that one writer in particular had been sharing about her own life. At the time, Finch had consolidated a fair amount of power within the Grey’s Anatomy writers’ room and was comfortable throwing her weight around. She and the showrunner, Krista Vernoff, had become close and she was now regularly sharing stories with her colleagues about her cancer and chemotherapy but, in Einesman’s estimation, her demeanor and anecdotes didn’t square with the reality of actual cancer treatment. He was also upset with the dynamics among some of the writers; he specifically didn’t like the way Finch treated some of her colleagues. She would often bully other writers and regularly weaponized her cancer survivor status to silence critics. Einesman took his concerns to Vernoff and human resources. According to several sources, the concerns were ignored. A source close to the show countered that it was “patently false” that Einesman ever “alerted or questioned the veracity of Finch’s diagnosis.”

Shondaland is one of the most successful and prolific production companies in entertainment. Founded in 2005, the company has had a string of hits that include Scandal, How to Get Away With Murder and Bridgerton. At one point, ABC filled its entire Thursday night primetime lineup with Shondaland shows. From a writer’s perspective, landing a job at Shondaland could mean years of sustained employment. As a result, competition for those jobs is fierce. Reporters who work for the Hollywood trades will often play up the collegiality within Grey’s Anatomy and Shondaland but, according to several writers, that comity masks a pressure-cooker environment where everyone is desperately trying to fit in and prove their value.

The Grey’s room was made up of mostly young writers and one thing that’s not disputed is that Einesman, who is much older, wasn’t exactly popular in certain quarters. According to several writers, he was seen as an out-of-touch Boomer — largely because Finch was successful in painting him that way among her circle of friends on the show. He was ultimately pushed out. Says Finch: “I struggled with him sometimes because of his old-school generational perspectives.” Einesman declined repeated requests to comment but he did say via email: “Not sure who benefits from my input. And who pays a price.”

It wasn’t just Einesman whom she went after. “I know the people that she hurt and that she lied to and that she bullied and they were always people with less power than her, compassionate people with kind souls and she absolutely targeted them,” says a former colleague apoplectic that Finch has the temerity to be interviewed. “That’s what master manipulators do. What she’s done is absolutely unconscionable but she doesn’t have a conscience… She does not deserve to have a voice.”

Inside Shondaland, Rhimes and her long-time producing partner, Betsy Beers, worked hard to foster a unique creative environment. Shondaland’s Hollywood offices have a dedicated playroom where employees can leave their kids and the intended vibe was casual and low key. Empathy and trust were pushed as the primary corporate virtues. “I don’t want to sound sexist, but I never tried to lead like a man,” Rhimes told Time in a recent profile. “I was a single mom with kids. The idea that I would lead any differently than my needs required never occurred to me.”

Shondaland is supposed to be a company that rejects traditional hierarchies, where everyone was on equal footing but in reality — especially at Grey’s — it was a balkanized group of individuals with Finch quietly ruling over it imperiously. People knew not to cross her and while men were her usual targets she wasn’t afraid to go after her female colleagues and they were usually writers who had just joined the show making them particularly vulnerable.

“She was quietly volcanic and would seethe with no sound,” says another former colleague. Finch had her own chair in the writers’ room that no one was allowed to sit in even when she wasn’t present. Further complicating matters was the cozy relationship between Vernoff and Finch (“Krista and I spoke a similar language” is how Finch put it to me). It got to the point where Finch and Vernoff would do press junkets together. To the others the message was clear: to cross Finch risked crossing the boss. On at least two occasions, Finch was triggered in the writers’ room when another writer pitched an idea that cut a little too close to her imagined self. In both instances the writers were asked by management to apologize to her. “Elisabeth made people uncomfortable, that was her special skill,” says the writer.

Compounding matters, Finch started taking long leaves of absence, sometimes unplanned, which forced her colleagues to pick up her slack.

The Lived Experience

Certainly over the last decade, a debate began sweeping Hollywood concerning the “authorship” or “inclusion” principle. This principle insists that writers and filmmakers need to share the ethnic, cultural and experiential identity of their subjects. Outsiders, by dint of their identity, race and upbringing, the argument goes, are incapable of understanding the nuanced experiences of others. Shondaland embraced these principles and writers were strongly encouraged to become experts on what they were writing.

I asked Finch if any of that influenced her in any way?

“It wasn’t calculated as such but I would imagine that it did,” she says. “There’s a need to become known for something or to have some expertise. It was absolutely dead wrong to do that, but I can see how it might have brightened the spotlight. Culturally it became cooler if [the pitch] was based on something in reality but that was happening on a broader scale. I do think culturally having a special something that you can write to is super helpful. It still is.”

“But every once in awhile the thought would pop up that I wish I could tell Shonda because of the person that she is and because she has the ability to understand that people do really fucked up things but that doesn’t make them a fucked up person. She sees people and the antidote to shame is being seen.”

Shondaland is fiercely protective of its image and that of its founder. All employees enter into restrictive NDAs and as a result leaks about the company are rare. Executives rarely talk publicly, except in gushy company profiles. In one of those articles, in Fast Company, Beers said, “I think we do spend a lot of time talking about sharing and not bullying and standing up for what you believe in and taking care of each other.”

Rhimes was a co-founder of Time’s Up, the now-disgraced organization born out of the #MeToo movement, which just celebrated its five-year anniversary. Starting around 2017, scores of women in entertainment came forward sharing their personal stories of abuse at the hands of powerful men. Finch was one of them. In a 2018 essay for The Hollywood Reporter, Finch claimed she was the victim of verbal abuse by an unnamed male director on the set of the show Vampire Diaries.

“There is nothing unique about the harassment itself that I endured,” she wrote. “The ever-growing fierce choir that’s risen up in the last few months has made it clear: No woman in any industry is immune from sexual harassment and abuse…What was unique was that I was listened to the first time. Believed the first time. And, therefore, there was no ‘next time’ for me at this director’s hands.”

When I asked her, Finch declined to name who the director was but still stands by the story. I sought out Julie Plec, the showrunner on Vampire Diaries to see if she still recalls the incident. Through a representative, Plec declined to comment.

“If the cancer was a lie, well then, it’s more than possible that her accusations of abuse were also a lie,” says Finch’s first boss, Rick Cleveland.

As for her former colleagues at Shondaland, Finch has nothing but kind things to say. “I didn’t walk around thinking that I have this secret and that I was going to get caught. I didn't stand there on my wedding day thinking, ‘Shit, I haven’t told her this’ because it was buried so far down. And I didn’t think your [March] piece was inevitable particularly because I didn’t think I bothered anyone. But every once in awhile the thought would pop up that I wish I could tell Shonda because of the person that she is and because she has the ability to understand that people do really fucked up things but that doesn’t make them a fucked up person. She sees people and the antidote to shame is being seen.”

Neither Rhimes, whose Shondaland was delighting in the tale of Anna Delvey while another con woman sat among them, nor Vernoff has ever publicly addressed the fallout from Finch’s demise.

The Marriage That Fell Apart

Finch lives in an old southern Colonial-style home which sits on nearly two acres of land that’s dotted with towering, majestic oaks. It’s a narrow, hillside property which tiers up several levels. I’m not allowed inside her home during my visits. We talk on her deck; nearby, there’s a hot tub, a koi pond and an old abandoned exercise bike.

She’s holding a copy of the Vanity Fair article written about her and we’re going through it line by line. She’s marked up and annotated the margins and it’s clear she’s pored over the story dozens of times.

“What’s so upsetting to me about it is the idea that I had stolen Jen’s identity,” says Finch.

The Vanity Fair article painted Finch as a vampire, but in place of human blood, Finch sucked out the pain and suffering of her victims and then incorporated and mimicked that pain into her own life story. To read the article in a vacuum one might conclude that Finch started lying in 2018, only after she’d met Beyer. In reality, her lies had started years earlier.

There are two villains in the Vanity Fair piece: Finch and Beyer’s first husband, Brendan. Beyer and Brendan had met at a military academy. They were married for 18 years and in the midst of a bitter divorce, Brendan committed suicide. According to Vanity Fair, Brendan physically, sexually and psychologically abused Beyer for years and was also, at times, abusive to their five children.

The story of Elisabeth Finch requires entering a world of shifting truths and a blurring of fact and fiction. This presents a journalist with an opportunity to come along and seize the role of the reliable narrator and that’s what the writer, Evgenia Peretz, did. After securing the participation of Beyer, Peretz was granted access to a trove of personal information — emails, texts, letters, and cell phone records — and the journalist laid out, in painstaking detail, the ways in which Finch was a generational con artist who was, in some ways, even more dangerous than Brendan.

Yet, just when you think you understand this saga, there’s always one more plot twist. In the course of reporting this article, The Ankler learned that questions have long swirled about the mental health and well-being of Beyer. Mary Beyer-Diebold is the mother of Brendan and in December 2018 she became the temporary guardian of her five grandchildren after Beyer had a dissociative episode which prompted Child Protective Services to step in. A dissociative episode is a medical term that describes a period of time when a person has a mental break from reality and their surroundings. In this instance, Beyer had been driving with two of her kids in the backseat when she pulled over to the side of the road, got out and walked away from the car. After several minutes, she realized she didn’t know where she was nor where she’d left her children and had to call the police.

Asked about the accusations leveled against her son, Beyer-Diebold says Brendan did suffer from paranoid schizophrenia, which caused all sorts of strange and erratic behavior, but only later in his life.

“The situations that are described by Jen could be out of intentional spite and anger or they are the figments of a deep-seated paranoia and delusional thinking,” Beyer-Debold tells me. According to Beyer-Diebold and several other sources, Beyer often shared that she was suffering from a range of illnesses, the symptoms of which never quite manifested. The point here is that, in this tragic tale, there really is no reliable narrator.

“It is not my intention or desire to speak badly of Jennifer,” Beyer-Diebold tells me. “She is a troubled individual who is now charged with raising the couple’s children alone. My only interest in responding to this story is to shine the light of truth on it so that Jennifer’s attempts to vilify Brendan are exposed and are seen in the context of Jennifer’s fragile reality.” When texted for comment several days ago Beyer directed me to her lawyer. Multiple emails and phone calls to the lawyers were not returned. I ask Finch for her assessment of the Brendan situation. “I believe women when they tell me they’re survivors,” she says.

What Does She Do Now?

“I don't understand why my story is on such a public-facing stage,” Finch tells me in what would be our final interview.

It’s actually not that difficult to fathom. What makes Finch’s betrayal particularly striking is the stage on which it occurred. Grey’s Anatomy is not just the longest-running show of its kind on television, it’s a cultural institution. To call its long-time viewers fanatics risks underestimating their devotion. Browse any of the online fan forums and you’ll get a powerful sense of the emotional attachment longtime viewers have, not just for their favorite characters, but for the writers and producers. As a soapy drama, Grey’s trades in emotionally-charged, real-world themes — love, mortality, female empowerment, victimhood and equity. It demands an emotional buy-in. Finch became a star of the show by leading her colleagues and fans to believe that she was the real-life embodiment of the show. When it was revealed that she had been lying, it was almost too much for her colleagues and fans to bear.

A chunk of our final conversation was spent discussing an upcoming photo shoot that would take place at her house. She was worried about the logistics and weather and on several occasions she asked who the hair-and-makeup artist would be. After the shoot, she emailed to ask if she could have some of the extra photos that weren’t used. She was particularly interested in shots showing her crying.

And now, Finch tells me she is planning her own next act.

Eight months after slapping Chris Rock, Will Smith is doing press for his new movie, Emancipation. Google Martha Stewart, who was convicted on felony charges and served about five months in a federal prison, and the top hits are about her homemade hot chocolate and her latest sexy selfie. Mel Gibson, who has a history of anti-Semitic and racist statements, recently starred alongside Mark Wahlberg in a movie called Father Stu, currently airing on Netflix. Why not Elisabeth Finch?

At our final meeting at a cafe in Venice Beach, she looks me right in the eye. “I could only hope that the work that I've done will allow me back into those relationships where I can say, ‘Okay, I did this, I hurt a lot of people and I'm also going to work my fucking ass off because this is where I want to be and I know what it's like to lose everything,’”

What would be the show that feels she could most comfortably write for right now?” I ask.

“Handmaid’s Tale,” she replies.

“I've struggled with that show a lot and I love what they're doing in the world of redemption and what redemption looks like. And what accountability looks like. It's taken a lot of hits because people have wanted certain survivors, characters who are survivors, to act a specific way. They want them to be less angry or less this or less that, and characters are reacting in all different types of ways to pain and to suffering.”

Writing for that show, Finch says, “would be a dream.”

This woman is loathesome, self-absorbed, and self-pitying. She bullied vulnerable people. I don’t think she has learned anything from her experience other than getting caught has consequences. I don’t care what childhood trauma she may or may not have suffered. She doesn’t deserve this much ink. Redemption requires remorse, and I’m not seeing that in anything she says.

Selfhausen syndrome.