Stalked: A ‘Baywatch’ Star’s 13-Year Nightmare

For the first time, an actress reveals the private, shattering hell caused by an obsessed fan

Alexandra Paul is an actress with more than 100 movie and television credits. She lives in an unnamed state in an unnamed small town with her partner of 30 years, Ian Murray, and their two naughty but very cute cats.

I place my grocery bags in the back seat and am starting my car to leave the parking lot in Santa Monica. Suddenly, the passenger door opens. As soon as I see who has slipped into the passenger seat, I start screaming.

I grab wildly at the door handle, leap out and start running to the store to beg for a security guard . . . but there are footsteps right behind me. I double back to my car and frantically lock the doors. There is banging on the window, urgent shouting. I cover my head, lean into the steering wheel, try not to look. I have been repeatedly advised never to interact. That rewards them, encourages them. But I have no choice, here I am — reacting, interacting, losing all the calm and resolve I worked in therapy to achieve.

I am being stalked.

This has been going on for 10 years. I’ve spent more than $60,000 in legal fees, hiring private investigators and installing security systems to try and protect my house. I check the street every time I leave home, avoid interactions with fans and rarely go to public events. I have been swatted, my husband has been hit by a car driven by my stalker, my elderly mother has been harassed at her home in another state.

The Santa Monica police arrive within minutes, but the stalker is already melting into the crowd of shoppers. The policeman is young and, from the way he keeps telling me to calm down, it’s clear that he thinks I am a hysteric who had a falling out with a friend. That is because my stalker is a woman. A white European woman, conventionally attractive, neatly dressed and 20 years younger than I am. I have always felt having a female stalker has meant that my case is not taken as seriously as if it were a man — even though female celebrity stalkers commit violence at the same rates as men.

I beg the cop to follow the stalker because I need to know what vehicle she is driving this week. She rents different cars, which makes it hard to know when she is lurking outside my home. I know the more upset I get the crazier I look, but I can’t help it. Especially because he is still standing there, and she is getting away. Again.

I have taken out restraining orders, my stalker has been investigated by the FBI, arrested, jailed and deported to Germany. But nothing has deterred her from her fixation on me. She always comes back. At my gym. When she rented a bedroom one block away. When she found me alone on hiking trails. When she falsely told police my husband was beating me. When she crashed his workplace to falsely assert he was a pedophile.

I have no idea why she picked me out as the object of both her desire and her hatred. I had never seen her before that fateful evening in December of 2011 when the doorbell rang and I innocently opened the door, seeing what seemed at first just a young woman and her little brother. That simple unwitting gesture of being home at the wrong time altered the course of my life.

‘As Soon as Hairs Go Up on the Back of Your Neck’

The subject of celebrity stalking brings to mind high-profile cases, like the man who tried to impress Jodie Foster by attempting to assassinate President Ronald Reagan, and the murder of John Lennon by the longtime Beatles fan who became infuriated by Lennon’s quip that the band was more popular than Jesus. (I will not use the name of any perpetrator in this article as experts advise that you should never give a stalker the satisfaction of seeing their name in print.) But it was the murder of the young actress Rebecca Schaeffer in 1989 that was the catalyst for the Los Angeles police department to form the Threat Management Unit (TMU) the following year, working with studios to identify problem fans and protect public figures.

Schaeffer, who starred on the sitcom My Sister Sam, was shot point blank by an admirer who was angry at her for a bedroom scene she filmed in a movie after the TV series ended. He had appeared several times at the Warner Brothers lot where her series was taped, asking to see her — once armed with a knife — and had been turned away by security guards but never apprehended. After paying a private detective $250 to find her home address through DMV records, the stalker rang her doorbell and, when she answered the door of her apartment building thinking it was a script being delivered, fired a gun at her chest. Rebecca Schaeffer was 21 years old.

The Threat Management Unit is a unique team within the LAPD. It has seven officers who work on about 275 public figure cases a year, including the harassment of politicians, high profile executives, athletes, musicians, actors and influencers. They are skilled at identifying and stopping inappropriate pursuit before things go too far. In fact, only 30 or so of these cases get to the point where charges are filed each year. The unit works closely with the police department’s mental health teams to deal with the complicated motivations of the stalker. Detective Pete Doomanis, one of three supervisors at TMU, says, “As soon as the hairs on the back of your neck stand up, I want to nip it in the bud. Then I can connect them to appropriate services, to their families, or get them into diversion programs. I sit right next to a psychologist and there is not a day that goes by that we do not consult together on a case.”

Detective Doomanis is the kind of guy you want on your side. Tall and broad shouldered, he has the formal manners and crew cut of a military man. He came on to my case seven years in, after my stalker had outlasted two previous detectives. Doomanis started out in patrol, then worked on robbery and sex crimes and in the Violent Crime Task Force. He was one of the pioneering officers in the cyber support unit, which monitored social media for criminal activity. Because the internet is a common way that stalkers track their victims, he was recruited to the TMU in 2018.

The advent of social media makes combating stalking both harder and easier, Doomanis tells me. It’s more difficult because celebrities are often so open, posting what they’re doing and where they’re doing it, and writing so personally that someone with mental illness can feel a deep connection. And public figures post a lot of photos that inadvertently give away clues to their whereabouts. “We have cases where stalkers have identified the mountains in the distance in a video and figured out where their target was,” Doomanis says. “Remember, these individuals spend as much time at their job — which is tracking their celebrity — as we do. Eight to 10 hours a day is not uncommon.” On the other hand, he continues, the internet “makes my work easier because the stalkers post too. They comment about their obsession on Instagram, in Reddit chat rooms, on TikTok.”

Doomanis believes 100 percent of A-listers in the United States “always have some type of pursuer, whether a true stalker or someone exhibiting stalker-like behavior.”

The ‘Smart and Athletic’ Baywatch Babe

I was one of those actresses who felt lucky to have such sweet fans, never a dirty letter or nasty comment in the bunch. My career started in 1982 when I was 18, and through my twenties I had lead roles in studio movies with Kevin Costner, Tom Hanks and Jeff Bridges. I was a regular cast member for five years on the TV series Baywatch when it became the most watched show in the world.

At that time, there were only a couple gossipy celebrity magazines and The National Enquirer, but even with all the tourists who came to watch us film on the beach, I felt safe. I was known as “the smart, athletic one,” so the fans who approached me when I was out and about were more interested in talking about triathlons or electric cars than ogling.

For the next 15 years, I worked happily in lead roles in more than 50 forgettable independent films or TV shows. After I hit 48, a producer told me I was “too old to play a mother and too young to play a grandmother,” and, although I was still working and recognized daily in the street, it was clear my star was no longer rising.

Which is why it was so surprising that my stalker suddenly invaded my life at this moment in my career.

When the doorbell rang at dusk in mid-December of 2011, I opened my front door to find a slight, dark-haired woman in her twenties dressed in Lululemon, standing calmly with a towheaded boy about 6 years old. In a quiet voice tinged with an almost imperceptible German accent, she asked if her little brother could use the bathroom. They lived three hours away, she explained, and had been playing at the beach nearby. Always the people pleaser, I invited them in. I made small talk with her and introduced my husband Ian while the little boy used the toilet.

The next day, a note was left at our door, thanking us for our kindness. A few days later, some chocolates with another note. Shortly after that, a third note apologizing for the other notes and making a request for the little boy to personally give me a picture that he had drawn. Ian called the phone number she had left and told her, in no uncertain terms, to leave us alone.

For nine months, she did.

Then she moved into a bedroom in a house just a block away. And so it began.

It was slow, at first, nearly imperceptible. She found me at the community pool and made small talk. Wanting to be polite, I responded. She’d appear on the trail outside my house when I was hiking, so I stopped walking alone.

Then she joined my gym and always chose the cardio equipment next to me. I started working out earlier and earlier to avoid her, but she showed up earlier and earlier too. It was eerie how she always knew where I was.

It all crept along so slowly. Which not only makes stalking so difficult to prosecute but also makes the victim second guess her instincts, especially when the stalker is not initially aggressive. Maybe it’s my imagination? Maybe it’s just coincidence?

I alerted the management at the gym, but there was nothing they could do. So I left that gym because they could not legally require her to leave.

Then things started escalating. After I left the gym, she accosted a staff member and accused him of being my spy. One day, she cornered me in a parking garage, desperate to talk to me, and tried to physically prevent me from walking away. I was able to bring the first of many restraining orders against her — but none of them worked. She violated them constantly, and by the time the police arrived, she was always gone.

As time went on, her attitude towards me vacillated from awkward adoration to hatred for my husband (“If it wasn’t for Ian,” she told a judge at one hearing, “Alexandra and I would be close friends”), to a certainty that I needed rescuing from him, to anger at both of us for ignoring her, to an insistence that I really was in love with her.

Over the years, she distributed hundreds of posters all over our neighborhood claiming I was an antisemite (though Ian is Jewish), while simultaneously sending me notes that she could help me escape my marriage. Copies of one poster, which she plastered over a five-mile radius, declared:

Public Notice: Attention Palisades and Malibu residents! You have in your midst a neighbor who is not who she says she is. Alexandra Paul best known for her work on Baywatch has conspired with her husband Ian Murray to incriminate and create a nightmare for her friends. They intentionally, deliberately and with malice falsely branded a woman a stalker . . .

This is not uncommon, I’m told by the experts. What starts off as a starry-eyed fantasy can turn dark and menacing when the celebrity ignores or rejects the stalker. Dr Reid Meloy, a researcher on stalking, writes, “What is oftentimes typical with celebrity stalkers . . . he yearned for her affection and at the same time was furious for her behavior.”

Another flyer, placed in mailboxes around our neighborhood, labeled us criminals and printed our home address in boldface. The stalker called the police saying she heard screams coming from our home, that my husband was beating me. The cops, knowing the history, didn’t respond until the next day and left quickly after seeing that I was unscathed.

My mother in Oregon received an unhinged, nine-page letter (my stalker had an uncanny knack for finding and contacting people around us) insisting I was her secret lover who needed saving from my violent, cheating husband.

Finally, several years after she’d launched her harassment campaign, law enforcement arrested her outside her home. Since she was in the country illegally with an arrest record for theft and now with a warrant for harassment, she was jailed and then deported back to Germany. She would be unable to legally return for at least a decade.

We breathed a sigh of relief. We thought it was over.

We were completely wrong.

Hollywood Victims Spawn a Law

The murder of Rebecca Schaeffer, which followed a vicious knife attack by an obsessed fan on actress Teresa Saldana in 1982, moved the California legislature to finally pass the world’s first anti-stalking law in 1990; all 50 states now have their own anti-stalking legislation. Criminal prosecutor Rhonda Saunders is a petite blonde who prosecuted some of California’s most notorious stalking cases. She established the Stalking and Threat Assessment Team in the L.A. District Attorney’s office, was L.A. chapter president of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and wrote a book about her experiences, Whisper of Fear. The True Story of the Prosecutor who Stalks the Stalkers.

“The first stalking law was not helpful,” recalls Saunders, who is now retired. In fact, “as a prosecutor, it was useless. You would have to look for other charges instead. So I went to our legislative deputy and said, ‘We have to rewrite the law.’”

She was met with resistance at first, but when a secretary who worked at the California state capitol was shot in the parking lot by her stalker ex-boyfriend, the legislators had a change of heart and Saunders was able to get the changes she wanted.

A stalking charge now encompasses malicious, willful, unwanted and repeated contact with another through letters, calls, electronic mail, gifts, social media comments or showing up in person. It requires a credible threat with the intent to put the victim in fear for their own safety or the safety of their family. And the victim must feel afraid for their well-being. “Stalking is a crime of mental terrorism, to destroy the victim’s life from inside,” says Saunders. “That fear element, putting the victim in terror, is the stalker’s way of gaining control of the victim.”

Saunders is proud that she insisted that harassment made “by all electronic means” be included in the law’s text, because it now covers technologies like email, text and social media that were not around then. She says she was actually thinking about pagers, which were prevalent in 1993, because she had seen so many stalkers terrify their victims by sending them messages through pagers that read “187” — the California penal code for murder.

Getting a stalking conviction is still not easy, Saunders says, especially when so much harassment is completely legal: contacting someone, giving gifts, driving in front of a famous person’s home. Fortunately, the TMU has found that in nine out of 10 celebrity stalking cases, it can stop any escalation by warning the stalker that if they continue they will face, at a minimum, a charge of “annoying or harassing electronic communications.” Detective Doomanis also tells the offender directly, “If you feel like you need to speak to this person, call me first.”

He says that for all the hardened criminal cases he has worked on in his career, it wasn’t until he started working in the TMU that he became hypervigilant for his family’s safety, because stalkers have also shown up at his own door.

While ex-partner or workplace stalking overwhelmingly involves male perpetrators, celebrities draw out a larger percentage of female pursuers (though still not as large as male stalkers of public figures). Women stalkers have the same likelihood of becoming threatening and violent, but their behavior tends to be less physically dangerous than their male counterparts. Although the TMU has found that warnings from law enforcement to the suspect early and in person discourages escalation in most cases, it can sometimes enrage the offender or inflate their sense of self-importance, encouraging further stalking behavior.

Ex-partner stalking has a greater than 50 percent chance of violence, but celebrity stalking is at just 2 percent. People often shrug off celebrity stalker stories, believing this kind of fixation comes with the territory of having fame or wealth, that it is a trade-off for an otherwise glamorous life. But the psychological impact can’t be overstated. Harry Styles, who in 2019 had an obsessed fan camp outside his London house, said he had persistent feelings of anxiety and dread even after the man was arrested. He upgraded his security, installed a panic lock on his bedroom door and hired a night guard.

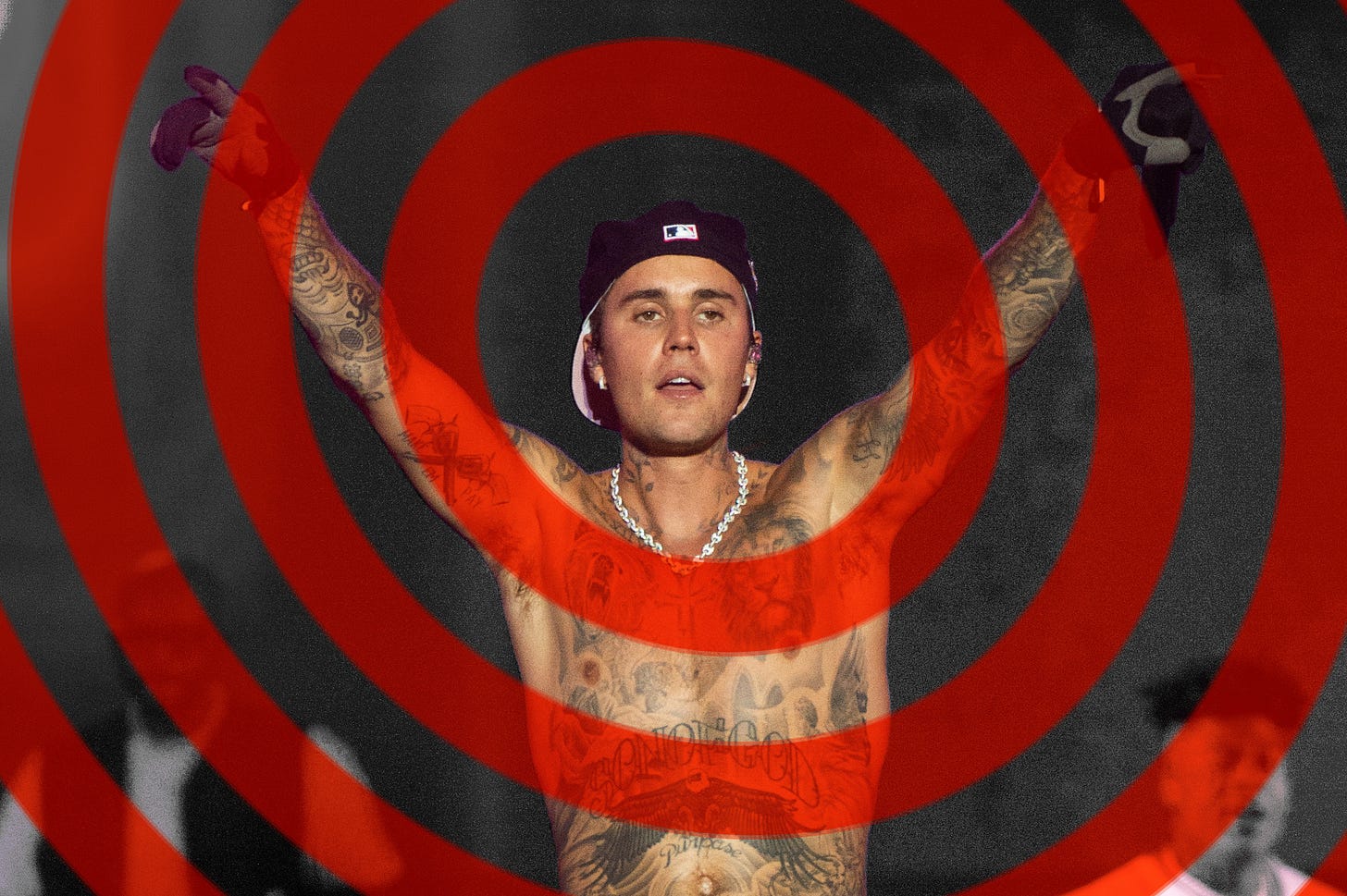

The obsessives who become angry and resentful towards a celebrity are the most dangerous. When Justin Bieber did not respond to fan letters, an inmate who was infatuated enough to have a Bieber tattoo on his leg paid two others to castrate and murder the young star. When the plot was foiled, he later told The Atlantic magazine, “If I was free, here’s what I’d want to do — put Bieber in a cage, rape him repeatedly, and put it on YouTube.”

Terrorizing My Husband to Get to Me

From another continent, my stalker was still pursuing me. She sued me for trying to run her off the road and kill her. I was puzzled at first, but then remembered the incident: I had spotted her car in the parking lot as I was exiting my dry cleaner, so I left as quickly as possible. As I drove up the hill to my home, I was terrified to see her racing up behind me at 90 miles an hour, trying to catch me. Then she veered past me and drove on. I was thoroughly spooked, and if anyone felt afraid that they were being run off the road, it wasn’t her. Luckily, the judge saw how crazy the accusation was and dismissed it, but not before it cost us thousands of dollars in legal fees.

Within two years, my stalker had reentered the United States (through Canada) and launched what was probably most damaging attack of all: an online campaign against my husband, accusing him of pedophilia.

Ian is a successful triathlon coach, and although companies and clients knew the accusations were false, monstrous allegations like that can tarnish the best of reputations. Even cyberstalking experts are relatively powerless to counter them. “Don’t ever make the assumption that a person with mental illness is of any impaired intelligence,” warns Dr. Scott. “I've known severely mentally ill people who are wildly, wildly intelligent.”

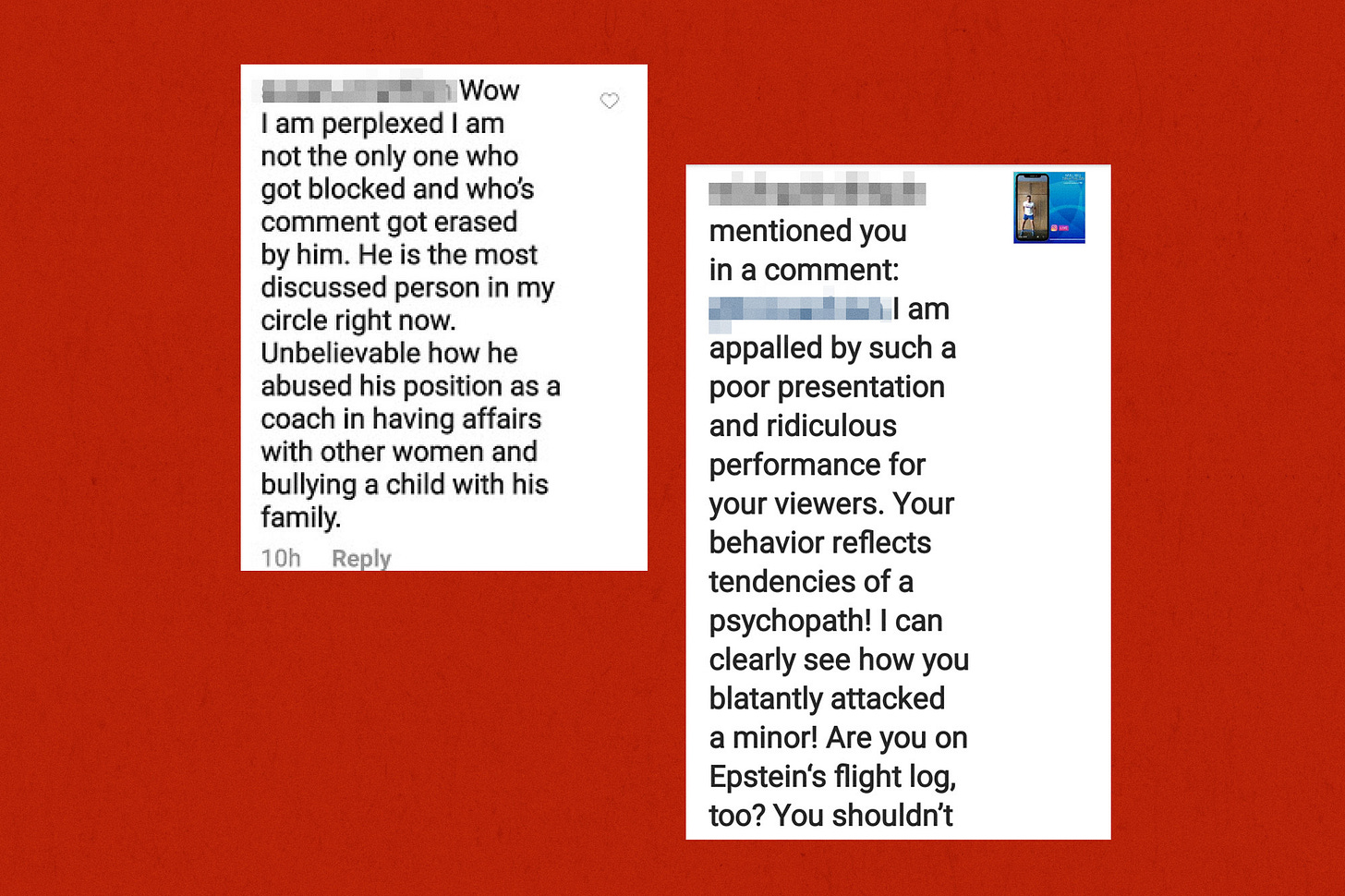

The stalker posted a barrage of accusations to triathlon-related organizations all over the country. As head coach of the L.A. Tri Club, Ian was hired to host a series of Instagram Live sessions for new triathletes headed to their first race. She crashed them by flooding the comment sections from various fake accounts:

“You are a true embarrassment to triathlon. Aren’t you embarrassed for putting your hands on a young athlete?”

“Your behavior reflects tendencies of a psychopath. I can clearly see how you blatantly attacked a minor. Are you on Epstein’s flight log too?”

“My best friend Malin in Sweden just informed me of this man who molested a 10-year-old boy.”

There were so many disruptions, in fact, that Ian had to end the Instagram series after just two sessions.

Another time she swiped a headshot from the social media account of an Australian triathlete and used it to make a fake Instagram account to comment in support of the false accusations. “Yes,” she wrote as the Australian athlete, “we have even heard down under about what Ian has done.”

At the same time she was doing all this, she was sending me messages urging me to leave my husband because she and I belonged together.

“Alexandra you don’t need to waste your time. You better start educate yourself about narcissism and trauma bonding.”

And: “#FreeAlexandra from her abusive husband.”

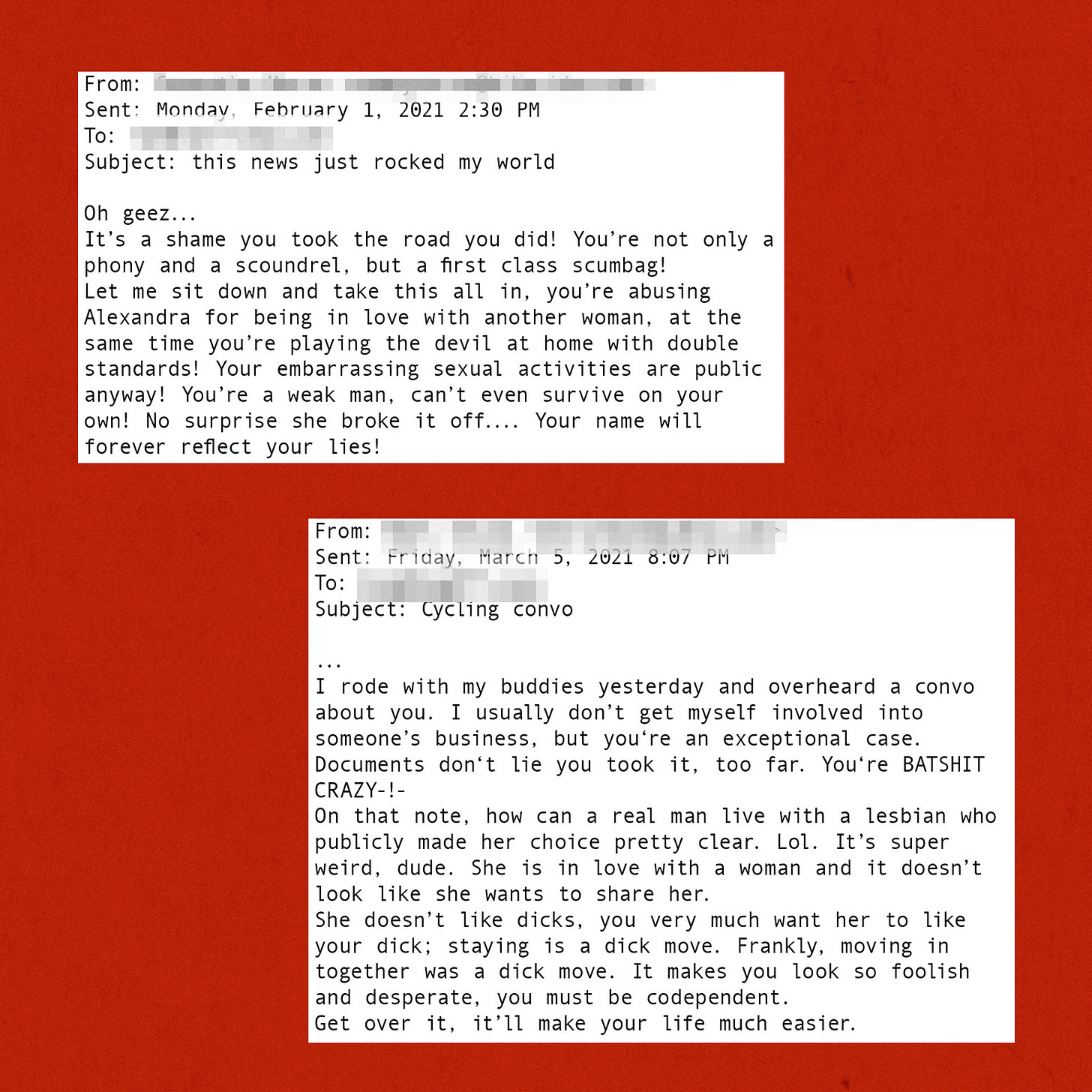

And to Ian directly: “You‘re BATSHIT CRAZY! On that note, how can a real man live with a lesbian who publicly made her choice pretty clear. Lol. It’s super weird, dude. She is in love with a woman and it doesn’t look like she wants to share her. She doesn’t like dicks, you very much want her to like your dick; staying is a dick move. Frankly, moving in together was a dick move. It makes you look so foolish and desperate, you must be codependent.”

And: “IAN you are such a douche no morals and values, spiteful and vindictive. I have a hard time wrapping my mind around what you have done to your spouse and a family. Must be really exhausting being you, especially when you're always trying to make people believe you are something you are not. You think you are the fucking king! I call it an irrational sense of entitlement.”

Soon afterwards, when our sharp-eyed mail carrier notified us that she was sitting in a van outside our home, Ian went out to photograph the license plate. She drove her vehicle straight at him. He bounced off the hood, landing hard on the pavement, scraped and bruised, as she drove away.

Lewd Messages, Porn, Restraining Orders

In a study by stalking researcher Dr. Reid Meloy, female newscasters and female leads on TV series tend to attract the most stalkers. Two beautiful actresses playing strong, single characters with a touch of quirkiness on a long-running show had 10 and 20 pursuers each. Female newscasters are particularly vulnerable as they look directly into the camera, build a daily rapport with their audience, are not playing a fictional character and often share personal details in onscreen banter with co-anchors.

Detective Doomanis notes that internet influencers, who depend on followers and likes, are also especially at risk because of the frequency and intimacy with which they post and the ease of contacting them through their social media.

And this isn’t just an American phenomenon. In a survey of German media personalities, 79 percent reported being stalked at some point in their career.

People who stalk public figures are different from the obsessed ex-husband or disgruntled employee bent on revenge. Politicians inspire angry, bitter reactions while entertainers, news anchors and athletes often attract people with delusions of a close relationship with the celebrity. Doomanis recalls one case where a tennis player opened a door for a young woman, and that is all it took for her to believe they had a special connection; no amount of reasoning could convince her otherwise. She followed him for years.

This is why celebrity stalking can get complicated: a restraining order often delights the perpetrator because it is proof of a reaction from the celebrity. I have had an effect. I am being noticed. The celebrity who has been warned never to interact with their harasser — because this fuels their pursuit — must interact with them when seeking protection through the courts. When I made my initial filing, my stalker responded with three retaliatory restraining orders (based on fictitious incidents, one of which was that Ian came at her with a knife) that put us time and again in the same courtroom.

This was not just frustrating, time-consuming and expensive. It was downright creepy. I knew what the stalker would be wearing each time because it was exactly what I had worn at the previous hearing.

And the restraining orders never stopped her — she broke the first one 29 times.

Madonna had to be subpoenaed to appear in court to testify against her stalker, who had scaled the wall of her home and threatened to slice her throat “from ear to ear” if he couldn’t have her. The prosecutor was Rhonda Saunders, who had insisted on bringing the case to court over the star’s objections. "I feel incredibly disturbed that the man who threatened my life is sitting across the room from me,” Madonna testified, “and we have somehow made his fantasies come true. I'm sitting in front of him and that's what he wants."

Saunders has no regrets. She asked Madonna to testify so she could explain how terrified she was to be so close to her stalker. “We have to have the victim in the courtroom,” Saunders explains. “If they aren’t, the stalker is going to feel empowered — Oh she must really love me because she refused to testify against me — and that just feeds into their obsession. We can’t make our case and they are going to be right back on that celebrity’s doorstep — or worse. I know it’s unpleasant, but this is something that needs to be done.”

Dr. Scott Musgrove, the forensic psychologist who worked closely with Detective Doomanis for over seven years, agrees. “People will say, ‘Oh, it’s just a piece of paper.’ And they’re right — that piece of paper will not keep a violent person out of your home. But it is the foundation for the actions that you are most likely going to have to take over a long period of time. Many security companies, many agents, will say Do not file a restraining order because then it will become public record. I am telling you right now, file the fucking paperwork. If you don’t file the paperwork and something happens that puts them in front of a judge, the judge will say, ‘But no one filed a restraining order.’”

Dr. Musgrave is passionate about his job, but he is also funny and friendly — when you have a Zoom call with him, the pronouns “he, him, y’all” appear next to his name onscreen. He still has the bright energy of the professional Disneyland dancer he was in his 20s. Musgrave spent two decades in casting and production before dramatically switching careers to practice as a criminal psychologist, counseling inmates at California’s Corcoran State Prison and working with sexually violent predators. At TMU, he consulted with police and detectives to “help mitigate threats before they become threats.”

To determine whether someone is a budding stalker or merely an overzealous fan, it is vital to determine a criminal and mental health history early. Many celebrity stalkers do not have steady or full employment and have fixated on other public figures in the past. Most of them warn their victims before they escalate, so it is important to read all letters and social media comments. Letters and gifts from the pursuer should be clocked for a changing attitude: from love to resentment to hate to revenge is a common trajectory. Intensity and repetitiveness also differentiate the besotted fan from the stalker.

It can be difficult to make a charge that fulfills all three requirements of the California law (repeated, unwanted contact; a credible threat; a victim in fear for their safety). Gwyneth Paltrow’s stalker was sent to a mental institution for eight years after harassing her by, among other things, showing up at her parents’ house, insisting they get married or else, and sending many lewd messages and sex toys. “There were shopping carts of all the pornography,” recalls Saunders, who prosecuted the first case. After the stalker’s release, he resumed sending gifts and letters, which led to a second trial. Paltrow testified how terrified she was "because the communications completely defy logic.”

That, however, is not enough for a stalking conviction — the messages were unwanted and the victim had fear for her safety, but the jury did not believe he intended to hurt her this time. The man was acquitted.

There is reluctance to give publicity to someone hungering to be near fame (my stalker contacted TMZ and other outlets every time we were in court, much to my horror). In fact, only 60 percent of the TMU’s caseload is celebrity stalking, because many of the A-listers who have had trouble at one time or another hire private security teams to do threat management assessment and protect their client without involving the police.

A well-meaning entourage might even try to protect the celebrity by not informing them of the problem. Detective Doomanis says this is a mistake, as it leaves them more vulnerable to unintended interactions with the stalker. Saunders agrees, but also for a legal reason: if the victim does not know about the stalker, they cannot be in fear for their safety, and therefore there can be no stalking charge.

In 1999, Steven Spielberg’s entourage did not tell him a man had trespassed onto the family property several times while the director was in Ireland shooting Saving Private Ryan. When the stalker was finally arrested — with three pairs of handcuffs, boxcutters, duct tape and a diary detailing the sexual violence he wanted to perpetrate on Spielberg — Saunders insisted the director be told about the predator because, “I can’t file charges unless I hear him say, ‘I am afraid.’”

When Spielberg was informed, he was understandably scared for himself and his family. He testified that he had nightmares worrying that the stalker might show up on the Saving Private Ryan set with a gun and, because the director was filming huge battle scenes, everyone would just assume the man was an extra.

Spielberg’s stalker was sentenced to 25 years to life, and when he came up for parole in 2023 Saunders made sure she was at the hearing to argue that he should remain in jail. He now has to wait five more years for another opportunity in front of the parole board, and Saunders vows she’ll be there again in 2028. “Stalkers don’t get rehabilitated,” she says flatly.

Dr. Scott believes “the majority of celebrity stalkers emerge from a base of what we call delusion.” Delusional disorder is holding beliefs that are false despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It is a psychotic disorder, but it is harder to treat than other psychoses because, while there are medications that can mitigate symptoms of auditory or visual hallucinations, none work very well on delusions.

Someone with delusional disorder makes the facts fit their narrative. Dr. Scott gives a real-life example. A young and successful actress was shooting a film overseas. “They've hired all local extras, and they need a security guard,” Dr. Scott recounts. “So they get a fitness influencer, and this actress playing his boss has no lines with him, but they shoot all day one scene of her walking through the office, dropping her briefcase, looking at him and giving him a nod. That was the match put to the mental illness this young man had been struggling with for years. He's in a coffee shop, and he believes the actress is sending him messages through the music that's being played through the speakers. It's like a code, he thinks to himself, She's taken these lyrics and she's sending me a message that we're supposed to be together forever, or that I should come see her in Hollywood. So it's a misinterpretation of the data around him.”

After inundating the actress with Instagram messages and gifts, this young man did come to Hollywood. She had moved out of her home for mold remediation, and he moved in. When groundskeepers flagged the weird dude living in the house, he was apprehended.

Dr. Scott interviewed him after his arrest. The stalker insisted that the actress wanted him there because she had left health supplements and food in the kitchen, and a gym was set up in the yard. To him, these were clear signs she cared for him. No amount of reason could penetrate his reality. “There is a wild mental gymnastics that occurs at the level of delusional thinking,” says Dr. Scott.

This stalker had erotomania, or de Clérambault's syndrome, which is a subtype of delusional disorder. Erotomania is the belief that someone — often a public figure — is in love with you when they are not, and what often follows is an obsession to be nearer to the object of infatuation. It might begin with tracking their movements, fantasizing about meetings, studying their social media. And then it might escalate to personal encounters and even violence in an effort to fulfill a ferocious certainty of a happily ever after ending. Margaret Ray, who believed she was David Letterman’s wife, trespassed onto his property several times, stole his car from his driveway, insisted her young son was his, and was found sleeping on his tennis court.

The most unsettling aspect of erotomania is that often the only thing that can interrupt the delusions is turning their gaze onto someone else, or death. The man charged in 2023 for stalking Drew Barrymore then turned his attention to Emma Watson and was arrested again. After Madonna’s stalker was released from a mental hospital, he began tormenting Halle Berry. Letterman’s stalker Margaret Ray later shifted her obsession to astronaut Story Musgrave and served jail time after trespassing on his property. She committed suicide at age 46 by kneeling in front of a train.

Dr. Scott says that sometimes the interruption of incarceration can reset the brain. “When they go to jail, they are no longer able to feast on their celebrity every day,” he says. “The change in environment, the dose of reality, can make a big difference. If one of the correctional psychiatrists is able to work with the inmate to get them on medication, that can help lower the noise inside the fixation.” He adds, “Sometimes a judge telling them they’ll go to state prison if they offend again might have an effect.” The stalker will still insist, “I know she is in love with me,” but they realize the stakes are too high to continue their behavior.

Rhonda Saunders, however, doesn’t agree. “The only safe stalker is the one who is taken off the street, so the victim can breathe.”

We Hide, Only to be Found Again

In 2022, 11 years after our nightmare began, Ian and I slipped out of Los Angeles in hopes of finally living in peace. We quietly sold our Pacific Palisades home, got special new IDs that protected our identities and rented a house under an LLC. We thought we had escaped.

She found us within six weeks.

We knew because she plastered our new neighborhood with flyers that contained our names and address. Since she had crossed state lines, the FBI got involved. But in the face of an obsessive, the law is often slow and ineffective. It took nine months and another violation of the restraining order before she was finally arrested and sent to jail — after attacking the arresting officer with a pen that also had a secret recording device in it. (I have no idea what her intention was with it.)

When she was in Germany, I later learned, my stalker had been diagnosed with breast cancer and uterine tumors, but she had shunned medical care there to sneak back into the U.S. It was a stunning demonstration of how all-consuming an obsession can be.

In the fifth month of her incarceration, the L.A. prosecutor’s office asked if we would agree to her release so she could spend her last days at home. We said yes.

My stalker died at the age of 41 on July 29, 2024. Which is, bizarrely, my birthday.

Because I followed the rule of not engaging with my stalker strictly, I know very few personal details about her. Despite all her time on the internet, there was very little the cyber expert we hired was able to find on her, and the FBI and ICE are tightlipped.

I will never know why she picked me. Maybe she watched me on Baywatch, which was very popular in Germany, and saw herself in the slender, dark haired, tomboyish actress on the show.

I am still working through the guilt of my initial politeness to her, which probably reinforced her delusion that I was interested in her. The stress placed on Ian and the damage done to his career because of her harassment — because of me — still haunts me. Delusional disorder is complicated by the fact that there is often a kernel of incentive that the stalker has to go on, and I literally opened the door to that, and helped her to succeed in her dream of being part of my life for 13 years.

When I share this with Detective Doomanis, he says you can never know what will trigger delusions—merely choosing the same variety of apple at a grocery store could serve as a secret sign to an incipient stalker of a deep connection.

Nevertheless, we have some control, and I am writing this article in hopes that no one has to go through an experience like mine. Here is some advice, gleaned from my own experience and from the experts I’ve spoken to over the years:

- Keep every letter that seems a little off. Document every interaction with someone who is getting weird. I began writing down every touch point with my stalker just days after she first came to my door, which was important in court to build a case against her. And helpful because the stalking lasted 13 years; I ended up with 263 pages of notes chronicling her harassment.

- Listen to your spidey sense. I knew there was something off about the initial encounter with my stalker, but I kept being polite. Stop being a people pleaser and protect yourself.

- Monitor your social media regularly to flag any overtly sexual, aggressive or persistent comments, and to track any changes in intensity and frequency.

- Contact LAPD’s Threat Management Unit or local law enforcement to assess the threat early. Detective Doomanis and Dr. Scott both say that an early encounter with law enforcement is often enough to stop escalation.

- File the fucking restraining order.

- Tell your family, friends and co-workers about the offender, so they can be on the lookout too. My stalker showed up at my mother and my sister’s homes on several occasions, and harassed friends through social media. In one study of 61 threats, 11 were directed at those around the celebrity.

- Follow Detective Doomanis’ advice and be careful about how personal you get on social media. Rhonda Saunders worries specifically about anything that shows off a public figure’s home. “They show windows and doors and the best way to gain access to the victim,” she says. “Your stalker is going to be reading everything you put out there, so don’t make their job easier for them”.

- Use a public data wiping service to get rid of your personal data on the internet (Doomanis says everyone would be surprised about how much information is out there on you.)

- Don’t sign photos or interact with fans using expressions of love or affection, as this can mislead the mentally ill.

- If the stalker approaches, do not interact with them. Ignore, ignore, ignore. I second guessed this often, thinking if only I give her what she says she wants, which is to talk to her, she will leave me alone. But I know now that it would have just encouraged her fantasies.

- Plan a strategy for a bodyguard or friend to intervene if there is an encounter with the stalker in person.

- If your stalker is jailed, join Vine (Vinelink.com), a victim notification network with information like where your stalker is incarcerated and when they are to be released.

My stalker changed me forever. Interacting with fans had been a beautiful part of my life, but now I am wary when someone approaches. Ian and I have withdrawn more into ourselves. We once believed in the tacit communal contract to respect each other’s personal space and tell the truth, but we learned this social fabric is flimsy and permeable. That may be the biggest loss, because with it goes trust, and all those whimsical encounters with other human beings that enrich our days.

Ian and I expected a Law & Order episode, where you call the authorities and everything gets wrapped up smoothly and quickly. So it was shocking to have to deal with my stalker for 13 years. If she had turned her fixation onto someone else, I might have escaped sooner. But with many celebrity stalkers there is no happy ending — the only thing that can bring their obsession to a final conclusion is death.