Secret History of Alan Alda's M*A*S*H Dog Tags

At auction, it was revealed they were from WWII vets: a Black man from the South and a Jew from Brooklyn. I found their families

“There's an old saying among actors,” Alan Alda explains to me in an October phone call. “They don't feel like the character until they put the character's shoes on.” For Alda's most famous role — Hawkeye Pierce, the irreverent but skilled Korean War surgeon on M*A*S*H he played for 11 seasons — it was combat boots and dog tags that made the character. Indeed they were so meaningful to him that when the show went off the air they were the only two mementos he kept.

Alda wore the same pair of boots from the 1972 pilot to the 1983 finale (the most-watched TV finale in history, with 106 million viewers). They’re regular Army issue with “Hawkeye” written in black Sharpie inside. I assumed the dog tags would say something similar — “Hawkeye Pierce/Capt/Crabapple Cove ME/Next of Kin: Daniel Pierce.” But I was startled to find when the items went up for auction earlier this year that these weren’t props but authentic World War II dog tags belonging to two soldiers, a Black man from the Deep South and a Jewish guy from New York City. Equally surprising to me was that until Alda decided to auction the dog tags for charity (they fetched $125,000 from an anonymous American buyer), the fact that they belonged to real men was unknown to the general public. The tags mentioned two names never seen up close on the show: Morris Levine (which the Army spelled incorrectly as Morriss) and Hersie Davenport.

“First time I saw them was when I was getting ready to film the first shot of the pilot,” Alda, now 87, and host of the podcast Clear+Vivid with Alan Alda, recalled to me from his home in Long Island. “I remember getting absorbed in them right away, looking at the names on them, and I realized they must’ve been the dog tags worn by real soldiers. That really put me in touch with the imaginary circumstances of the show, much more so than if they had given prop tags that had the name of my character on it.”

Often when he was putting the dog tags on in his dressing room, seemingly obtained by the costume designers of M*A*S*H, he would ponder who the men were and where they served, even if they survived the war. The fact that there was only one tag for each, instead of the usual pair, made him wonder if they were alive or dead: “I didn't know anything about them other than their names.”

Alda wishes now he had been more curious. He was surprised to learn that Jamie Farr, who guested as the cross-dressing Corporal Max Klinger in the fourth episode and stayed until the very end, and Mike Farrell, who joined the show in season four as Captain B.J. Hunnicutt, had both told me they wore their own personal dog tags on the show. (Alda had served in the Army, six months on active duty at Fort Benning in New Jersey and another 18 months in the reserves from 1956-58, but never thought about wearing his own dog tags.)

Surprisingly, he never asked any of the other actors about their dog tags or shared his with them. “It's funny, but nowadays that would be a natural thing for me to go around the stage, ‘Let's look at our dog tags together to see if they're real.’ I've gotten so used to exercising my curiosity [on my podcast] interviewing people,” he says. “It didn't occur to me in those days to do that.”

Filled with curiosity, I began a hunt to find more.

FINDING LEVINE AND DAVENPORT

I hold a PhD in American History, an American Jew whose doctorate is about African American history. There is never one draft of history, as the saying goes, but a shared Final Draft if you will, one undergoing constant revision. On the occasion of Veterans Day, it is our duty to remember not only the extraordinary, but also the ordinary and “unremarkable” men and women who, when called, performed their duty and, if lucky, returned to live their lives as best they could.

It’s not possible anymore to figure out exactly how the dog tags ended up on the show. Neither veteran had a Hollywood connection and the costumers and prop masters from the 1972 pilot have passed away. The most logical answer is that both men donated or sold their uniforms to a used clothing store and costumers hunting for vintage clothes found them there.

But it was possible to learn more about the men with some digging.

Army records don't offer much beyond the basics. Census records for 1940 — after 72 years, the government opens the raw census data to researchers — didn't list anyone by those names (including a Velma or a Gladys, the next of kin named on their dog tags) at the addresses on their dog tags.

I was stumped. I asked a friend, a retired Army officer who's now a history professor for help. He not only found Hersie's daughter, Paula Davenport Johnson, who was born during the war, but got me an email address.

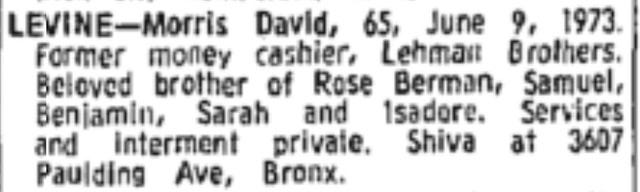

Morris Levine proved trickier. A Jewish guy in New York City with the name Morris Levine from that era is practically John Smith. I scrolled through The New York Times obituary page for the week after his passing (the auction house was aware the men had died and when) looking for an obituary. There wasn't one but I found a paid death notice.

Excitement was followed by disappointment. The only survivors listed were his siblings. No wife and no kids. Would anyone remember him? Stumped again, I turned to a journalist-investigator we've used in the past at The Ankler. Genealogical research isn't his usual cup of tea but he warmed to the challenge and soon located Levine’s niece Penny Apter living outside New York City.

Both women, Paula and Penny, were surprised someone was asking about their long-passed relatives and were blown away to learn about their connection to M*A*S*H. They had no idea. Each shared the story of the men behind the names that inspired Alan Alda in the creation of one of the most famous characters in TV history.

Hersie: Dancing and Easter Egg Hunts

At its core, M*A*S*H was a show about ordinary men and women, draftees for the most part, reluctantly called into service, so it's fitting that Hersie Davenport and Morris Levine’s lives weren’t all that different from Hawkeye, Radar, Klinger or the other characters.

Hersie Davenport was born in Mississippi on April 14, 1908, making him just a few months past his 33rd birthday when he enlisted in July 1942. It sounds old but the average age of soldier in WWII was 26. His Army records record him as Black — one of 900,000 African-Americans who served during the war — but Paula says that's not exactly accurate. Hersie’s father was an Irish immigrant and Hersie’s mother was Choctaw. Indeed, Hersie — no one knows where the name came from and everyone just called him Paul — was light-skinned enough that people often assumed he was Latino. Still, Hersie always identified as Black and Paula didn't learn about her Irish grandfather until high school.

Velma, already pregnant with Paula, traveled to Chicago with her husband for his induction into the military. She returned to her hometown of Texarkana to give birth and then moved to Oakland for family and work, getting a job at the Kaiser shipyards — think Rosie the Riveter.

Meanwhile Private 1st Class Davenport was assigned to be an engineer. He didn't see frontline combat like you see in the movies, but he was sent to Germany, where he was stationed until his discharge 10 days before Christmas 1945.

Paula doesn't know much about her dad's time in the Army. He didn’t talk about it. “It was in the past,” says Paula. She has the sense that he was frustrated by the segregation and racism in the Army. He thought he could do more and was never given the chance. About the only thing she can recall him saying about his Army days was his promise to never, ever eat Spam again — in the interracial Oakland neighborhood they lived in, Paula learned to love the Spam wasabi her Asian American neighbors made, but Hersie wouldn't touch the stuff.

After discharge, he got a job working the shipyards as well. Both Hersie and Velma, who continued working after the war, had good union jobs. He eventually earned a promotion where he oversaw others and that led to an offer of a managerial job at a tannery. Later in life he worked in a series of odd jobs, mainly doing light security work.

He loved to entertain. The Davenports had a nice house on a corner lot with a big yard and a chicken coop out in the back that was a gathering place for family and friends. Many of the workers at the tannery were from Mexico and when they returned from visiting family, they'd bring back huge sacks of pinto beans — a favorite of his — and he’d have a party where the kids would divide up the beans into smaller bags which he'd give out as gifts.

He loved to dance and to play his favorite records. Velma wasn't much of a dancer but Paula took ballet so he’d drag her out on the dance floor any chance he could and they’d cut a rug. He saw that his daughters graduated high school and went to college — education was important — and made sure they knew how to drive a stick. Paula went on to race Porsches and learn how to drive an 18-wheeler.

Some things from his Mississippi childhood stuck. He hated catching the girls barefoot in the backyard. He’d say when he grew up his family didn't always have the money for shoes and sometimes he'd go barefoot. But he could afford plenty of shoes for his family so not going barefoot was one of his firm rules.

When he got older he’d have the grandkids and assorted cousins over for Easter. He’d buy dozens and dozens of eggs for them to paint in the backyard. Then they'd all put on their pajamas — you know the ones with the sock feet — and have a sleepover in the living room. But sometime in the middle of the night he’d sneak upstairs to finish the night in his own comfy bed. After the holiday, he’d make sure they donated the leftover eggs to a charity that would use them.

He was still working security when he got sick at 62. He didn't say much, but Paula could sense the end was near when he pulled her aside for a private word. He said to her, “Baby girl, I will never have to worry about you or about you taking care of your mother and looking out for your sister.”

Hersie Davenport passed away on April 24, 1970. Velma survived him by 37 years, passing away in 2007.

Morris: One of Three Brothers Who Served

If Hersie Davenport's life represented the arc of the Great Migration of African-Americans out of the South, the end of legal segregation and the rise of a broad Black middle class, then Morris Levine’s life represented the wave of European immigrants who flocked to America in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Morris was born in Brooklyn in 1908, the second oldest of what would be a family of four boys and two girls. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Russia. Early on his father got sick and passed away, so his mother got a job managing an apartment building. The kids all left school early to work to help support the family. It’s not clear exactly what Morris did before he joined the Army in 1942 at age 35.

That next of kin listed on his dog tags? That was his wife — they got married a short time before the war — but while he was overseas she sent him a Dear John letter telling him she was divorcing him and that was that.

Corporal Levine was sent to the Pacific — also in a support role. (As Alda noted about both men’s roles, “It takes an army to get an army to war.”) The highlight of his time was meeting Brooklyn Dodger Pee Wee Reese and some other players — the Dodgers were Morris’ team — who had been drafted and getting a picture with them. All three of the older Levine brothers — Morris, Benjamin and Isidore (nicknamed “Wiz”) — served in the war. All three made it back alive. Morris was discharged on November 15, 1945, three months to the day after the surrender of the Japanese.

After the war, he got a back office job at Lehman Brothers. It was a time when you could get a good job like that without a college education and make a nice middle-class living. He was the sort of guy who knew everyone from the CEO to the office boys. Chick, that was the nickname everyone used, helped manage the Lehman’s company baseball team. He took care of his family, helping little brother Benjamin get a job at Lehman and living with his widowed mother until she passed away. He never married again after his divorce.

His niece, who knew him into her early twenties, remembers him as fun, gregarious and easygoing. He was family oriented and loved sports, especially, as noted, rooting for the Dodgers. And in the Six Degrees of Separation category: Morris’ sister and Alda’s sister-in-law actually crossed paths at P.S. 97 in the Bronx where one was a teacher and the other a parent.

After leaving Lehman, he moved to Miami Beach. Not that long after, he developed cancer. Morris “Chick” Levine was just 65 when he passed away in June 1973, a few months after M*A*S*H wrapped up its inaugural season that March.

This story has tugged at me since I first learned about it. It's more than that M*A*S*H is a show I loved as a kid and that I still watch in reruns often, or that Hersie’s journey out of the segregated South is the kind of story I told as a historian or that the Levine’s story reminded me of my own family’s — my Jewish grandfather also emigrated from Russia as a teen and soon joined the Army, serving as a sailor in WWI. We live in such divisive times where facile displays of flags or Support Our Troops signs are weaponized in some contest to proclaim one side more patriotic than the other. I found hope in this story.

At its best M*A*S*H was a show that celebrated the draftees. Much has always been made of the rebelliousness of the lead characters, the show's anti-war messaging and its arrival during the Vietnam War to overdraw the idea that it was a protest show. I've always thought alongside all that, M*A*S*H was deeply patriotic in the way it celebrated the everyman G.I. Joes.

Duty. Country. Family. Carving out a little piece of the American Dream for yourself. Those were the lives Morris and Hersie lived. That’s patriotism to me. Hawkeye Pierce in the end was a fitting tribute to them.

This is one of the loveliest things I have ever read

I served in my war and I write about my father's war, World War II. This is a really nice piece, reminding us who the real "heroes" are - the people who put their heads down and move forward, one foot in front of the other. Thanks for this.