'Organized Chaos': Remaking 'SNL' Brick by Brick

Jason Reitman, Jon Batiste and the 'Saturday Night' team on the immersive set, anarchy and music as 'the villain in the film'

Happy Monday to everyone, especially those of you I will see in six short days at the Montclair Film Festival! Tickets are still available for my onstage chat with a very special guest who knows his way around the season: Tom Bernard, the co-president and cofounder of Sony Pictures Classics. Plus I’ll be joined by two of my favorite awards-obsessed reporters, Chris Murphy of Vanity Fair and Chris Rosen of Gold Derby.

Our panel is called “Hollywood Awards Season: Who Wins and Why It Matters,” and the goal is to get into all the stuff that awards reporters sometimes take for granted — who’s getting tribute awards at regional festivals, who’s at the Governors Awards, who’s on the cover of which trade — and explain it for the audience. With that in mind, if you have any burning questions you’d like us to get into, we take requests! E-mail me at katey@theankler.com even if you won’t be in the audience in Montclair: You can hear our conversation on next week’s episode of the podcast.

Today, I’ve got the highlights from my expansive, incredibly entertaining conversation with the key players on Saturday Night — director Jason Reitman and five of his key collaborators on the film: production designer Jess Gonchor, composer Jon Batiste, costume designer Danny Glicker, cinematographer Eric Steelberg and sound mixer Steve Morrow.

Related:

The production was certainly not as chaotic as what we see behind the scenes of Studio 8H for the making of the first episode of Saturday Night Live in 1975, but it might have been just as inventive, from building a fully immersive set to building the score live every day after filming. And the affection you build from an experience like that is real. Before logging off the call early, Batiste dropped a note for the rest of the team in the Zoom chat: “I love you all so much. Onwards!”

A 'Diabolical Tease'

“When you work at SNL, you spend half your time in a stairway, in an elevator or walking down a hallway.”

That’s what Reitman knew from personal experience, having worked as a guest writer on Saturday Night Live back in 2008. And it’s what he aimed to recreate meticulously for his film Saturday Night.

Reitman kept the map of the studio in the back of his mind as he wrote the script with Gil Kenan, following Lorne Michaels (played by Gabriel LaBelle) through the very busy 90 minutes before Saturday Night Live premiered. But even before the studio could be built on that soundstage, Reitman had to take every step himself.

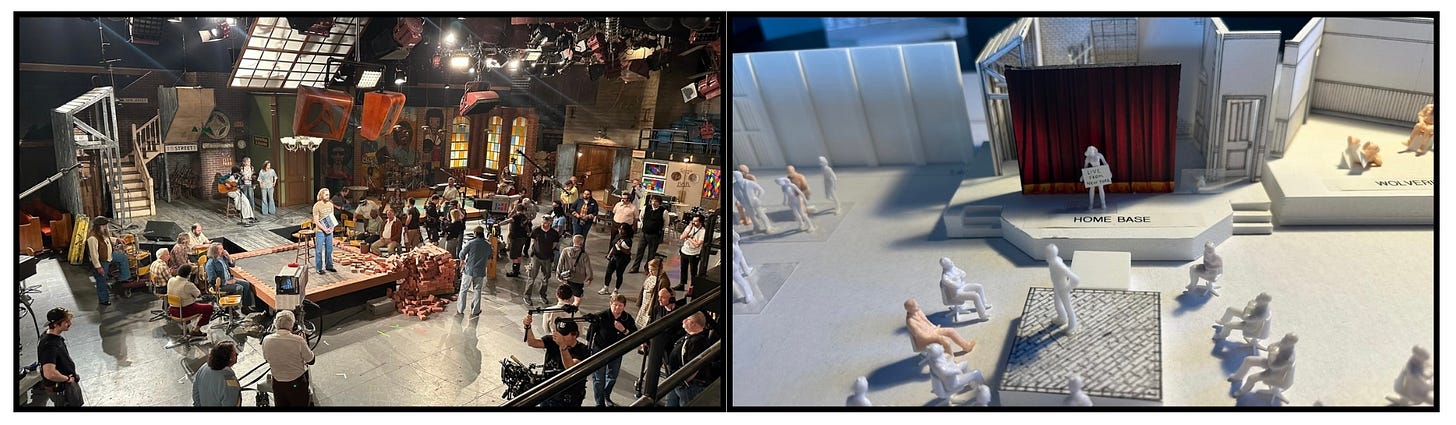

“It was something that I’d never done before,” says Gonchor, the production designer, whose credits include every Coen Brothers movie since No Country for Old Men. “We had taped out the whole set before we built it on a 30,000 square foot stage (taking over an Atlanta soundstage to build every corner of the iconic Studio 8H), and Jason took the script and went through that first scene. He read the lines and acted it out. That set the template for the whole thing.”

When I got on Zoom with Reitman and his crew, I wanted to focus on the film’s major opening scene, a bravura long take that captures nearly everything that makes Saturday Night such a joy to watch. After briefly opening on the sidewalk outside 30 Rockefeller Center, where a hapless NBC page (Finn Wolfhard) is struggling to give away tickets to the show’s first live taping, the camera floats through the studio hallways, introducing dozens of characters and the fundamental chaos of backstage life. John Belushi is there refusing to wear what would become his iconic bee costume; Chevy Chase arrives on the arm of his model girlfriend; Dan Aykroyd flirts shamelessly with both Gilda Radner and Laraine Newman.

Reitman’s goal was to build a set that would make both actors and audience “feel like they were dropped into a real place.” But he also had to get a camera through it. After that walk-through of the taped-off version of the set, he and Steelberg — Reitman’s DP of choice since 2007’s Juno — walked through the set with an iPhone and stand-in actors, figuring out how the camera could bob and weave through the crowded corridors. Steelberg calls the camera a “dance partner” with the actors.

“So much of the movie was about movement,” adds Reitman. “I think on other films, we've talked about cinematography, you could sit there looking at a frame for a long time thinking about, is this the right frame? That was never the conversation on this. It was, are we turning at the right time? Are we staying on that moment long enough? Are we getting to the right thing?”

The movement comes from the camera and from the frantic pace of so many of the actors, but it’s also there in the costumes — as Reitman points out, even the togas worn by some cast members in a destined-to-be-cut sketch were chosen for the way they moved. Glicker, the costume designer and another longtime Reitman collaborator, was charged with recreating some iconic costumes from the early SNL era, but found a way to make even those famous looks (or lack thereof) a source of mounting tension.

“For me, it was really about not delivering the iconic costumes too early,” Glicker says. “If I deliver the goods in the opening shot, there's nothing to build on. So I really wanted to sort of create this sort of really diabolical tease with the audience to just give them hints of what they came for, which is of course, the iconic show.”

Tick, Tick, Boom

Everything in Saturday Night works as if it has an ominously ticking clock behind it — as the real Lorne Michaels has said, “We don’t go on because we’re ready, we go on because it’s 11:30.” Saturday Night is fun to watch not only because we know all this stress will eventually give birth to a classic TV show, but because the tick-tock of the deadline is captured by Batiste’s joyful, percussive score.

“It's what I like to call an anti-score,” says Batiste, who also plays Billy Preston, the show’s first musical guest, in the film. “It goes against the normal paradigm of what you do with the score. It’s a mix between score and sound design, and also the music actually being the villain in the film.”

Any time a character in Saturday Night is in motion the score is right there with them, a syncopated reminder that there are 100 problems to solve before showtime. In that opening walk through the studio halls the score follows LaBelle’s Lorne beat for beat, overlapping with the dialogue from the dozens of people he encounters along the way.

Sound mixer Steve Morrow had the job of outfitting as many as 30 people with microphones for shots like this one, allowing them to drift in and out of camera and sometimes having background dialogue bubble up to the surface. “Don't worry about the overlaps, don't worry about what's going on around you,” Morrow remembers telling the actors. “Just play it like you're playing it. Let the actors be actors and let the script speak for itself.”

It can be hard to tell where Batiste’s score ends and the everyday clamor of a TV studio begins — which is exactly how everyone wanted it.

“There is an extreme level of difficulty to creating organized chaos,” says Reitman. “It is very tricky to build a set in which you can look in every direction from all angles where the lighting is all built in. It’s very tricky to create shots that go for five minutes where the lighting always works. It’s very difficult to have 80 background actors and 80 lead actors where there’s no hierarchy in the costumes. You never know who is suddenly going to be the main character of a shot.”

Reitman doesn’t include Batiste’s work in that rundown because “I don't even know how to explain what Jon Batiste did. All the other people on this call, at least I have a modicum of understanding of how they do their jobs. With Jon, I feel like God just channels through him and then the results happen.”

Building the Movie’s 'Heartbeat'

But Reitman and the rest of the crew actually got to watch Batiste at work in a way no other composer, that I know of at least, has ever scored a film. On set editor Nathan Orloff used an Apple Vision Pro to create a rough cut of each day’s work — over the summer Lamorne Morris, who plays Garrett Morris in the film, described the process to me with a bit of awe. When each day wrapped, Batiste and his band would change out of their costumes and gather around Orloff’s laptop, where the next part of their job would begin.

“You'd just watch the cut roll over Jon,” Reitman remembers. “You'd see him take it in, and then he would just turn to a musician and start giving them notes and turn to a percussionist and he would mouth out a beat. That live nature of what he wrote becomes the heartbeat of the film.”

Batiste credits Reitman with allowing him to “do my thing,” following the emotions sparked by those rough cuts to create “a musical allegory for the clock.” He continues: “Jason seemed really fearless in doing this thing that we didn’t know if it would work or not, because there was no finished cut of the movie. So it just felt like, wow, we’re going on a voyage.”

Brick by Brick

“There’s such a rhythm to everything that everybody on this call brought to the production.” That’s Jess Gonchor, the production designer, whose work might not seem to connect naturally to Batiste’s score. “We all had to create a rhythm with the costumes and the cameras and the lighting, and just create our own sense of pace to everything that we did.”

Morrow adds that they were all “in mourning” about the set having to be torn down, the place that Reitman described as a place for the cast to “genuinely bounce off of each other like wild molecules.”

One small part of it lives on, though. In the final moments before SNL is about to air, the show’s fictional crew finally comes together to build the real brick stage at the center of the set — one of many expensive flourishes that Lorne Michaels insists is essential to the show. The brick-building montage, backed by Batiste’s Preston playing “Nothing from Nothing,” is a handy metaphor for the ingredients of SNL finally coming together.

Gonchor knows the power of those bricks, too: He took one home with him from the set.