Rudolph Valentino's 15 Days of Tawdry, Tabloid Death

'Daily Mail', Drudge and the Murdochs owe a debt to Bernarr Macfadden, whose 'PornoGraphic' paper rose on the fall of the world's most famous matinee idol

Joe Pompeo writes about Hollywood history every other Saturday. His first column revisited Marilyn Monroe’s fatal overdose, dark echoes of which resonate in the Matthew Perry media frenzy. He can be reached at joepompeo@substack.com, and you can sign up for his personal Substack if you like what you read here.

On Aug. 22, 1926, Rudolph Valentino — the biggest movie star of the silent era — lay on a hospital bed in Manhattan, the life rapidly fading from his body. His pulse raced. His temperature soared. Doctors kept vigil at his bedside. He would not survive another day.

Valentino’s abrupt and unanticipated death, at 31 and at the height of his powers, wasn’t just a pivotal moment for Hollywood. It was an early tabloid tour de force, spawning an impossibly tawdry template for the media’s coverage of famous people.

Of course almost all media today can feel like tabloid media. Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal goes viral reporting on Elon Musk’s drug use and sex life, and even Murdoch’s own personal foibles, from his rapid-fire late-life romances to the Succession-like family feud played out in a Reno courtroom, are fodder for his own reporters. Donald Trump’s penchant for down-market news-making remains, while media elites obsess over a sexting scandal involving one of their own and a Kennedy turned Trump-supporting failed presidential candidate. Messy celebrity tragedies like Matthew Perry’s, meanwhile, continue to penetrate the national consciousness.

But the birth of American tabloid media — and modern celebrity culture — goes back a full century. Before there was RadarOnline, TMZ, Deux Moi, the Daily Mail or Drudge Report, even before there was the National Enquirer or Confidential magazine, there was the Evening Graphic. Founded 100 years ago this month — the most outrageous but largely forgotten newspaper in U.S. history — its coverage of Valentino’s death set a preternaturally high bar for tabloid shenanigans (including doctored images) while launching the careers of the most infamous Hollywood newshounds. Our tale begins with the Graphic’s eccentric founder, who could be a larger-than-life movie character in his own right.

'Sensationalism Will Be Used'

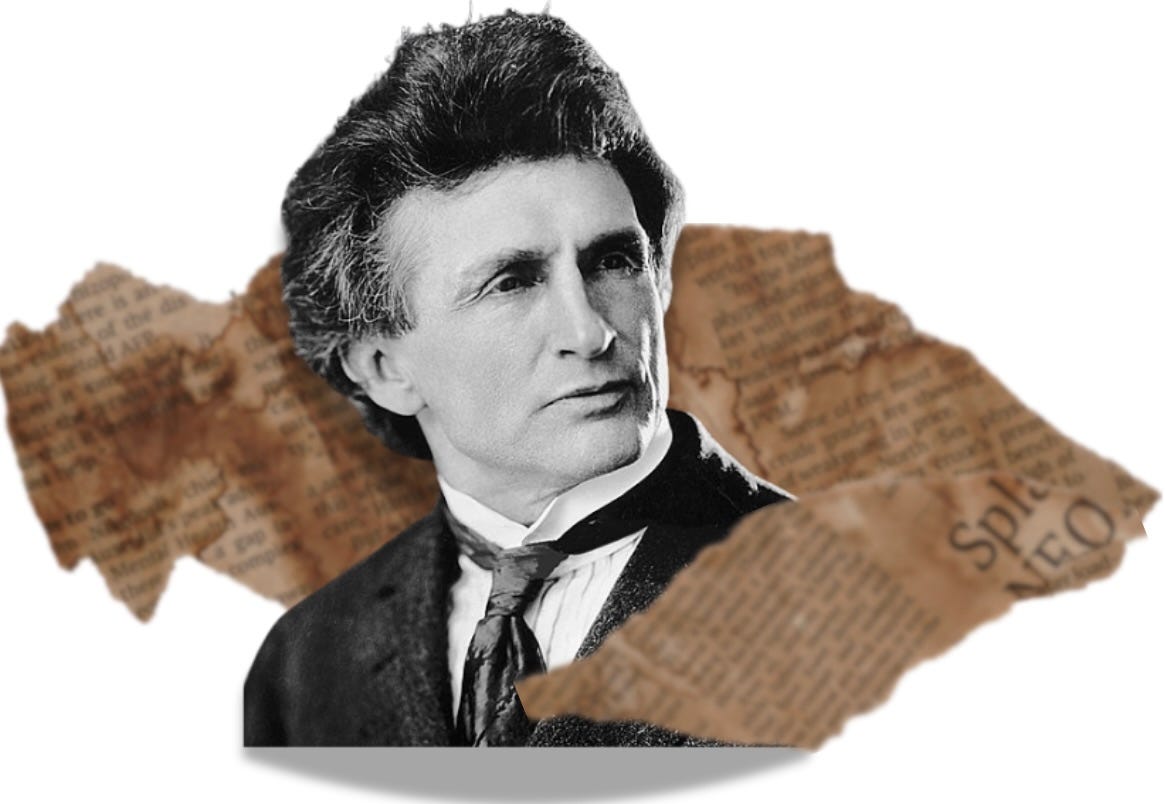

Bernarr Macfadden seemed tailor-made for the emerging tabloid press of the Jazz Age. Attention-hungry fitness fanatic? Check. Pioneering anti-vaxxer and proponent of snake-oil cures? Check. Fringe presidential aspirant who tried to establish a utopian health colony in central New Jersey and was known to walk barefoot into Manhattan from his Nyack estate more than 20 miles away? Check, check and check.

After building a publishing empire that included a slate of pulpy “confession” mags (True Story, True Experiences, True Romances, True Detective Mysteries, etc.), as well as his flagship Physical Culture, Macfadden set his sights on the tabloid craze that had taken hold in Manhattan (tabloid meaning both the more convenient size, without a fold, and sensational mirroring of images and words). The headline-heavy, photo-centric British newspaper medium had been imported to America by Joseph Medill Patterson — scion of the publishing dynasty behind the Chicago Tribune — who founded the New York Daily News in 1919 and turned it into a smashing success.

Five years later, Patterson was joined at the tabloid rodeo by William Randolph Hearst, who launched the New York Daily Mirror in a bid to overtake the News’s circulation, the highest of any American newspaper at the time. Now, as Patterson and Hearst girded for battle, Macfadden hatched plans to open a third front in America’s first-ever tabloid war.

Macfadden communicated his intentions in a telegraph to competitors on July 17, 1924: “I expect to begin publishing a New York daily newspaper that will be human all the way through. Illustrations will be an important feature of this proposed newspaper, and every possible means will be used to make it attractive and appealing. Sensationalism will be used where it serves good purpose.” (i.e. everywhere.)

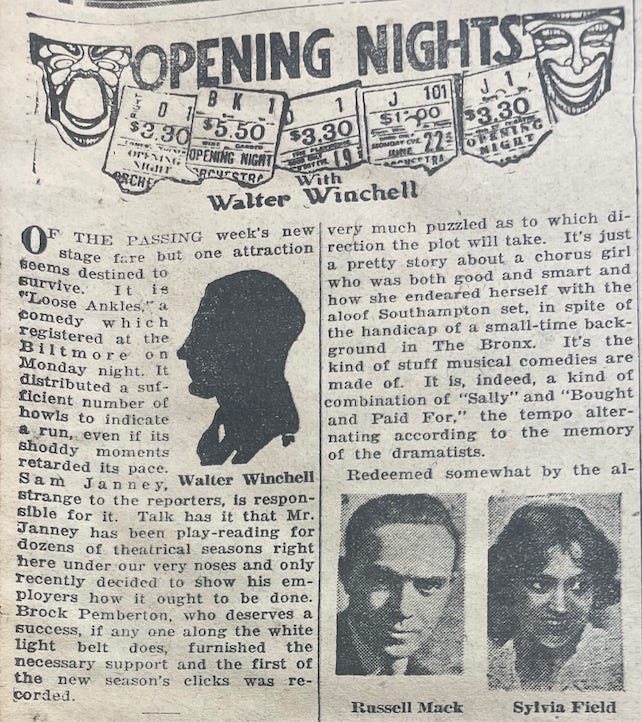

Macfadden bought the former Evening Mail building near City Hall and put together a staff. His first hires included a 27-year-old theater writer named Walter Winchell, who was brought on as the Graphic’s Broadway columnist.

Another recruit was Robert Harrison, who got his start as a copy boy. The Graphic apparently knew how to pick 'em: Winchell and Harrison — who worked alongside future movie director Samuel Fuller (Shock Corridor) and future television host Ed Sullivan — would become titans of celebrity journalism. (More on that to follow.)

The inaugural issue of the Evening Graphic hit newsstands on Sept. 15, 1924, and it wasn’t long before the paper earned a nickname befitting its spicy content: the PornoGraphic. Macfadden’s strategy, it appeared, was to out-tabloid his tabloid rivals. If the News was sensational and the Mirror lurid, then the Graphic was positively over-the-top. Macfadden, to borrow a line from a 1925 Columbia Journalism School thesis, had given New York “one of the most unusual news-publications it has ever seen.”

The Graphic, as Time magazine would observe decades later, “reported what nobody else would dream of printing” and “invented what it could not report.” (This formula would be replicated by subsequent uber-tabloids in the decades to come). It distinguished itself with relentless coverage of mega-yarns like the Peaches and “Daddy” Browning scandal, involving the divorce of a middle-aged New York City real estate developer and his teenage bride. It also became a magnet for libel litigation, such as the cluster of lawsuits it faced over a 1925 “exposé” suggesting that Atlantic City’s Miss America pageant had been rigged.

“The whole thing is a disgrace to American journalism,” declared Earl Carroll, a pageant judge and Broadway impresario — whom the Graphic would later skewer for a late-night scandal at his midtown theater, involving a naked teenage chorus girl and a bathtub full of wine.

The Graphic’s most memorable innovation was the composograph (see above), a proto supermarket-checkout-line art form in which the faces of story subjects were superimposed on body doubles enacting, say, the murder-suicide of socialites Sydney and Frances Brewster. Or Alice Jones Rhinelander removing her top during the courtroom proceedings for her marriage annulment. Or a bedridden Charlie Chaplin being comforted by his faithful furry friend. (It boggles the mind to think what Macfadden’s editors would have done with Photoshop or AI deep fakes.)

Chaplin wasn’t the only actor to get the Graphic treatment. Nearly two years after the Graphic first set sail, a different showbiz luminary was about to become wall-to-wall news — and the Graphic would cover the story like no other.

‘RUDOLPH VALENTINO DYING!’

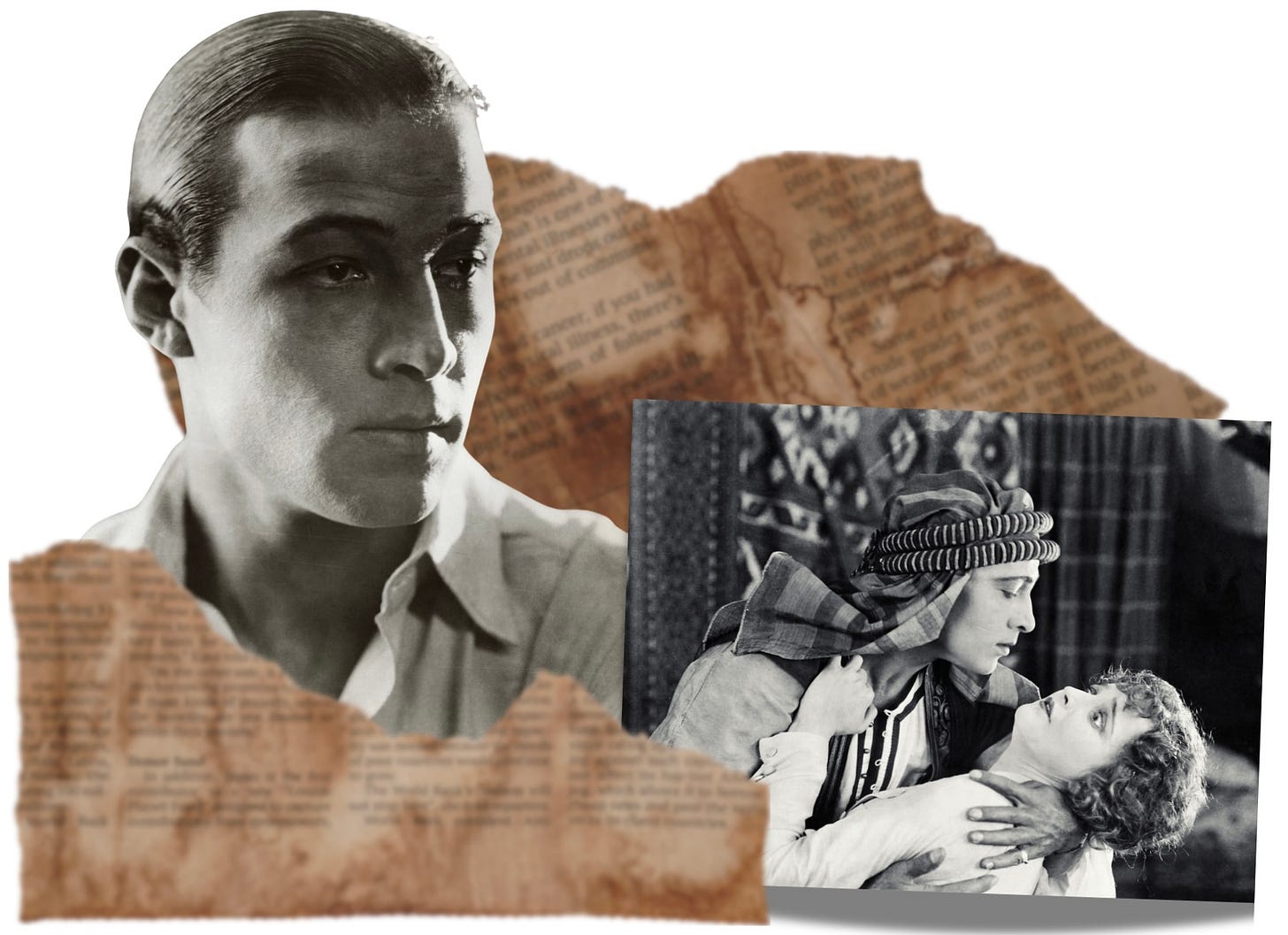

Rodolfo Pietro Filiberto Raffaello Guglielmi di Valentina d'Antonguella, better known as Rudolph Valentino, was born in Southern Italy in 1895. After a trouble-making adolescence, he moved to New York in 1913, where his good looks helped him land a job as a paid dance partner at Maxim’s Restaurant-Cabaret. In 1917, Valentino moved to Los Angeles, determined to make a name for himself in the burgeoning movie business. A series of bit parts led to his breakthrough role in 1921’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, followed by The Sheik that same year, both silent movies.

Valentino was a natural specimen for the celebrity-hungry tabloid press, which blossomed amid the ballyhoo of the Roaring Twenties. When Hearst’s Mirror debuted a few months before Macfadden’s Graphic, its front page titillated readers with a (real!) shirtless Valentino photo, promoting an “exclusive” about “the exercise and the care he takes to preserve his masculine beauty.”

Valentino was just as popular in the Graphic’s newsroom, considering such headlines as:

RUDY REVEALS SECRETS OF HIS CHARM OVER MILLIONS OF FEMININE HEARTS

VALENTINO TO AVOID WIFE

VALENTINO SAYS HE IS BORED WITH THE ATTENTIONS OF WOMEN

Valentino was more than just a sex symbol — he was the biggest movie star of the age, a cultural icon in the making. That he was at the top of his game made what happened next all the more shocking.

It was Aug. 1926, just weeks after the premiere of Son of the Sheik, a sequel (yes, even then) to the 1921 classic that helped propel Valentino to stardom. During a visit to New York, Valentino had been experiencing abdominal pain. On Sunday, Aug. 15, the morning after a shindig at the Upper East Side residence of Barclay Warburton (a Manhattan playboy and, as it happened, founding publisher of the Daily Mirror), Valentino was “seized with a violent convulsion.” When a doctor arrived at Warburton’s Park Avenue pad, he found Valentino in a condition so serious it warranted his immediate transport to Polyclinic Hospital on West 50th St., where the frightfully ill Latin Lover found himself on an operating table within the hour.

Valentino’s first wife, the actress Jean Acker, rushed to the hospital from her apartment uptown. She was joined by representatives of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, who had been alerted to their star’s dire condition. They waited anxiously until Valentino awoke from his anesthesia around 6:30 in the evening.

“Valentino was admitted suffering from acute appendicitis, as well as from an ulcerated condition of the stomach,” one of the surgeons said. “Both stomach and appendix were operated on. The latter was removed. While it is impossible to make a positive statement as to the probable result, it may be said that in 75 percent of such cases there is recovery.”

Those odds were enough to put the tabloids on Valentino death watch, a particularly auspicious circumstance for the Graphic. Its circulation trailed the News and the Mirror by a significant margin. Now, by applying its eccentric brand of tabloidism to a dramatic story involving one of the most famous people in the world, it had a chance to close the gap.

“RUDOLPH VALENTINO DYING!” the Graphic’s front page declared the morning after the operation. “Will the cinema hero on his deathbed marry Pola Negri” — the Polish actress-singer who had become the latest object of Valentino’s affections — “or effect a reconciliation with his first wife, Jean Acker, who rushed to his bedside last night?” Such burning questions! And all for just two cents (34 cents in today’s dollars).

Over the next couple of days, despite rumors from “the heart of Broadway” that he’d departed the earthly plane, Valentino at first seemed to rally. “Flappers Cheer At News After Report of Death,” the Graphic informed readers in its lead story on Aug. 18, although the sidebar was juicier:

You are alone with Rudy in the cab. It is after 4 o’clock in the morning. A driving rain beats against the taxi’s windows. The sleepy driver does not hear your cry for aid. The sheik has lost consciousness. What would YOU do? Marion Benda, beautiful showgirl in “Ziegfield’s Revue,” found herself in this situation early Sunday morning. Until last night she kept her secret, while all Broadway speculated on the details of that evening that had preceded Valentino’s collapse.

Day after day Valentino graced the Graphic’s cover. In lieu of actual news, there was no shortage of micro developments: “VALENTINO RALLIES AGAIN”; “VALENTINO ‘DOPED’ FOR PAIN”; “Flapper Throngs Cheer as ‘Sheik’ Sends His Thanks.” Or gratuitous filler: “‘Sheik’s’ Perfect Physique Praised by Chicago Medic.” Or rank speculation: “RUDY’S ‘BATTLE FOR LIFE’ ATTACKED AS PUBLICITY.”

Behind the scenes, Valentino had, in fact, taken a turn for the worse. Joseph M. Schenk, the producer and United Artists president who played an influential role in Valentino’s career, visited the deteriorating patient, who remained mercifully ignorant of his looming fate.

“I didn’t know I was so near death that Sunday,” Valentino told his mentor. “I am beginning to realize only now how serious my condition was.”

15 Days of Madness

Early the next morning, Monday, Aug. 23, Valentino slipped in and out of consciousness. By noon he lay in a coma. Father Edward F. Leonard — known as the “actors’ priest” for the breadth of his celebrity flock — came to administer last rites.

Schenk entered the room and stifled a sob as he watched Father Leonard place a cross — said to contain a relic of the original cross — on Valentino’s lips.

As he bent over his dying friend, “Well, Rudy, old boy, how are you?” he said.

Rudy’s eyes darted from those of the priest to Schenk.

His mind was clear. The eyes were bright. The corners of his mouth lifted, parted, as if to speak—to answer the low, cheery greeting.

The words were unspoken. The light died from the eyes and the lids drooped and fluttered. Father Leonard whispered a prayer

The face paled.

The smile faded.

Death!

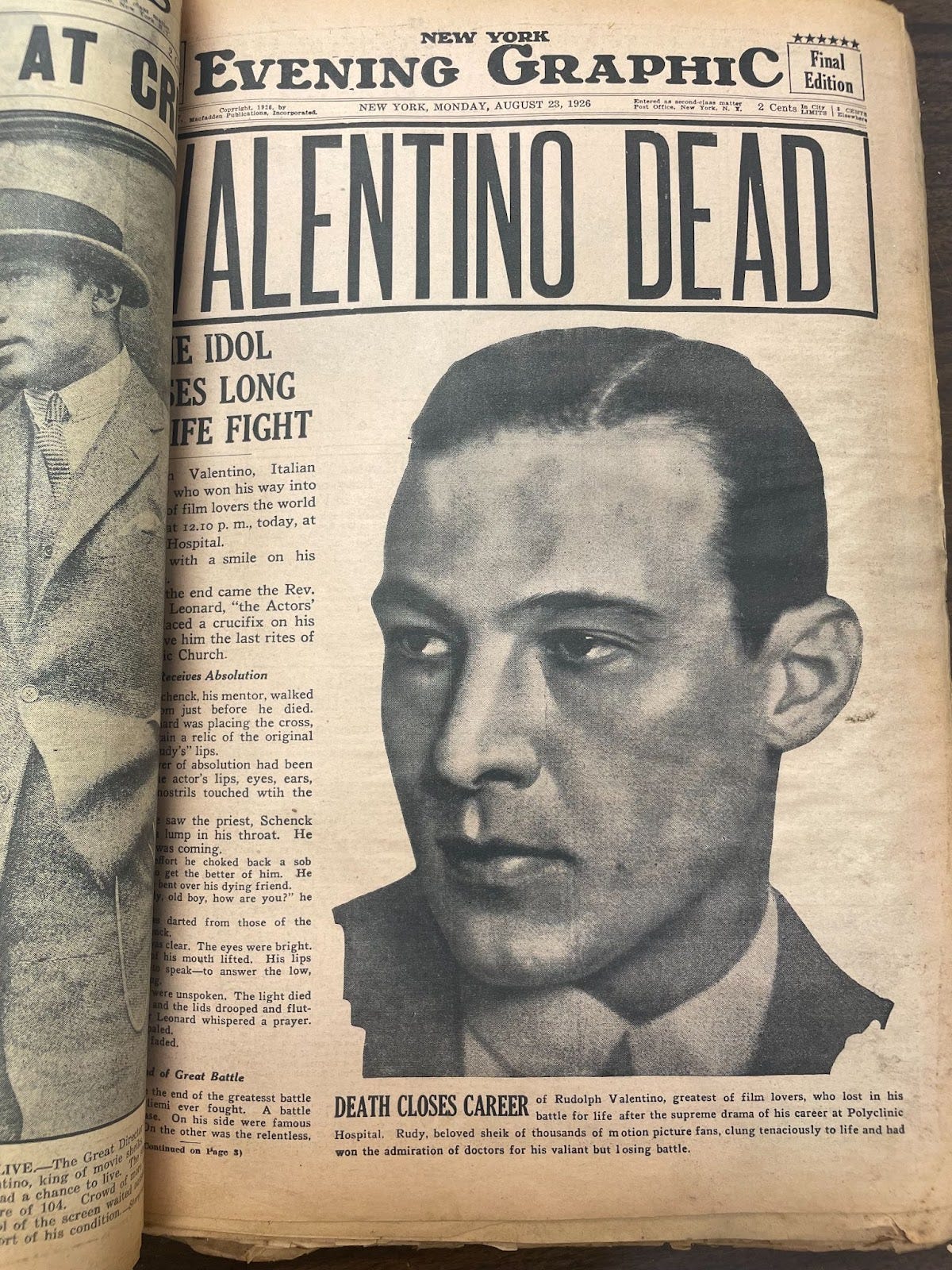

This account (presumably embellished) would appear a few hours later on the cover of the Evening Graphic, alongside a full-length headshot of Valentino in healthier and happier days.

For the Graphic, it was a rare coup over its A.M. tabloid rivals, which wouldn’t be able to deliver the blockbuster news to readers until the following morning.

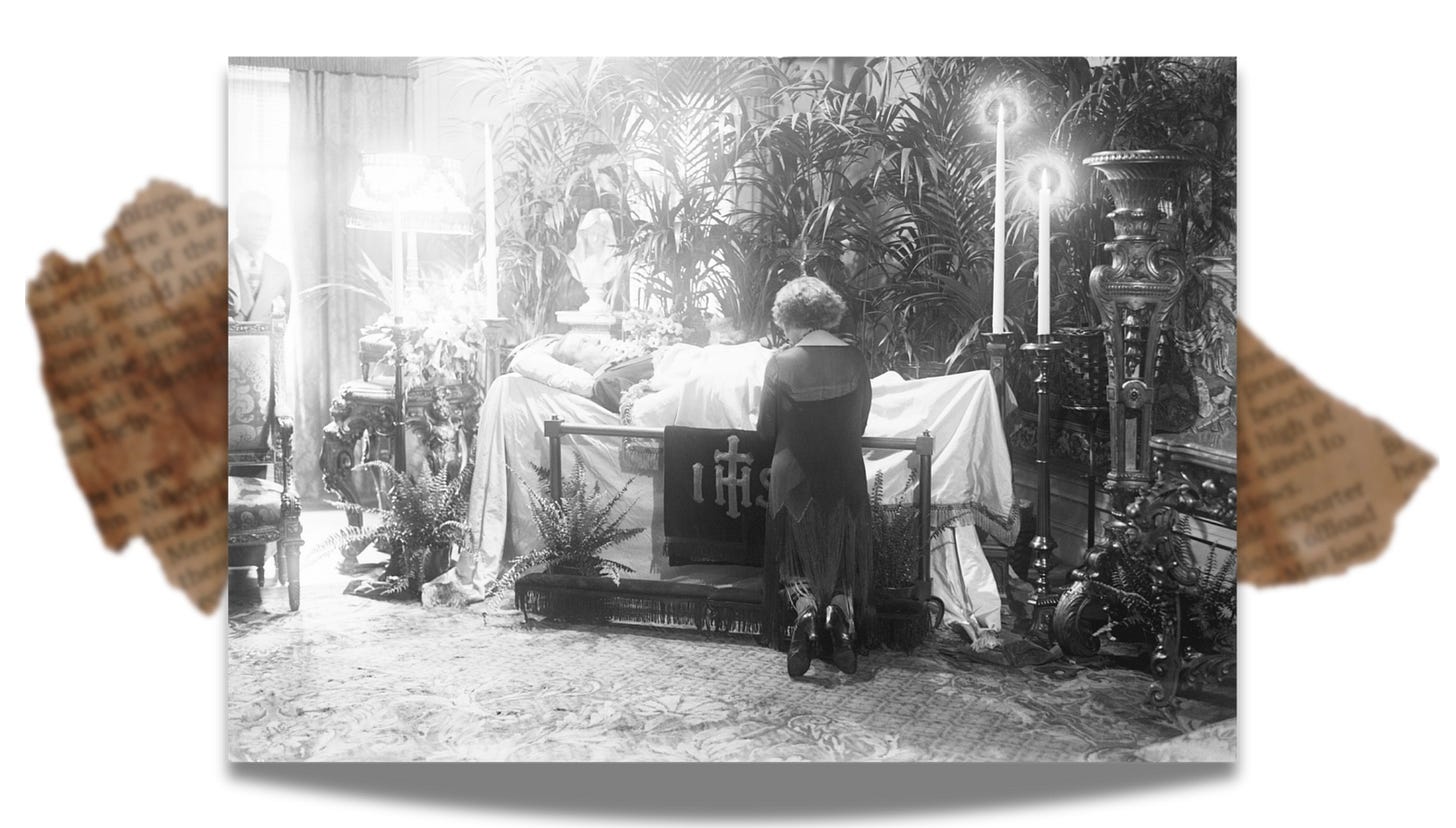

Macfadden’s worker bees snapped into action. One of them was a journalist named Frank Mallen, newly installed on the picture desk after a stint covering politics. As “pandemonium struck the Graphic office with the velocity of a hurricane,” Mallen picked up his phone and called “undertaker to the stars” Frank Campbell. (Campbell’s legendary funeral business, still active today, was the subject of a New York Times feature earlier this month. Its list of star-studded send-offs over the years includes Fatty Arbuckle, Greta Garbo, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, John Lennon, Heath Ledger, and many more.)

“Valentino just died,” Mallen said. “Are you getting the body?”

“Why of course we are getting the body,” Campbell told Mallen, who knew that Campbell’s publicity-savvy handling of the services would “make Valentino’s pictures more popular and profitable than ever.”

Minutes later, a pair of Graphic photographers were speeding uptown in a taxi en route to the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel. They took pictures from various angles of the famed “Gold Room” where Valentino’s body would soon be on display. One photographed the other lying on the catafalque where the casket was to be laid, part one of being able to utilize a human form to then create the composograph.

“Within an hour,” according to Mallen, “we had Valentino lying in state on our front page.” So masterful was the composograph that competing newspapers initially thought it was an authentic photo. Reporters only learned the truth when they descended on the funeral parlor and saw for themselves that Valentino’s body had not yet arrived. Back at the Graphic, the circulation manager came bursting out of his office. “It’s wonderful!” he exclaimed. “It’s the best break we ever got. The papers are going like hotcakes. We’ll be running the presses all night!”

The Graphic’s jump on the Valentino story set the tone for its smorgasbord of coverage in the days to follow, as Americans mourned en masse. Demand for the Graphic exceeded the capacity of its printing press. Rival cameramen trailed the tabloid’s photographers in fear of getting scooped. Every angle was exploited, from the despondent mobs thronging the funeral parlor — there was an actual riot on Aug. 24 — to the conspiratorial whispers of poisoning or suicide, to the autobiography that the Graphic happened to be serializing “exclusively for Macfadden Publications, Inc.”

“If we lose the questing child spirit,” Valentino had mused in one installment, presumably with the aid of a ghostwriter (no pun intended), “the child belief that just around each corner something new, enthralling and delightful is awaiting us, we lose more than half of the joy of living.”

The frenzy resulted in some of the Graphic’s most memorable composographs, including those inspired by a medium who claimed to have made contact with Valentino on the other side. One such illustration, as then-editor Emile Gauvreau later recalled, showed the deceased “entering the spirit world and meeting a number of celebrities who had passed on before him.” It increased the Graphic’s circulation by 100,000.

The climax of the saga — not only for the Graphic but the entire press corps — came on Aug. 30. An estimated 100,000 mourners lined the streets between Campbell’s funeral home on the Upper East Side and St. Malachy’s Church on West 49th St. Police mounted on horseback corralled the mobs. Despairing women fainted on the sidewalks. In the midst of the bedlam a team of “bootjackers” employed by the Graphic fanned out to hawk tens of thousands of copies of a special morning edition.

“Graphics were selling as fast as the super newsboys could take or make change,” recalled Mallen. “Hordes waited in queues to buy the papers, even mourners in cars waved for them.”

The entire episode, as Mallen further reflected, “had made a tremendous contribution to the Valentino memory — and inventory of his pictures.” Campbell was satisfied that his management of the funeral “had elicited the greatest adulation ever accorded a deceased member of the moving picture profession.”

Days later, at Campbell’s invitation, Mallen arrived at Grand Central Station and boarded a Los Angeles-bound train carrying Valentino’s silver-bronze casket. (“THOUSANDS VIEW TRAIN CORTEGE TO MOURN RUDY.”) A second funeral had been scheduled for Sept. 14 at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Beverly Hills. Given the sheer spectacle and hysteria that Mallen had witnessed in New York, he expected an ever greater uproar upon Valentino’s arrival in the world’s film capital.

“It didn’t turn out that way,” Mallen recalled. “The platform was filled with people but not one seemed to care about Valentino . . . Campbell was perplexed. Here, where he had anticipated a worship that would reach transcending heights and that certainly would take over all the headlines of newspapers everywhere, no one cared . . . The memorable wake for a movie personality who had captured the hearts and imagination of the rest of the nation had come to a dismal end as the sponsors found him a completely forgotten man in his own bailiwick.” (Maybe New York had simply wrung every last drop of sensation from the story.)

There was, of course, a more cynical interpretation. As The Nation suggested in a sneering but high-minded editorial, “If not for the body laid out in the funeral home, one might have thought that the final illness and death of Rudolph Valentino was one great publicity stunt . . . In the long run such journalism must be its own reward. A censorship which could destroy Bernarr Macfadden would be more likely to destroy many a brave pioneer of social idealism.”

Killed by Lawsuits

Valentino was interred at the Hollywood Forever cemetery on Santa Monica Boulevard. His death had created an all-too-familiar template: “Movie stars with rabid fan clubs and an active media breathlessly reporting every aspect of their lives.”

That’s from an article that the New York Public Library published on its blog in 2020. “Prior to Valentino’s untimely demise,” the article continues, “celebrity deaths were not the source of media frenzy and excitement they are today. In some ways, the drama of his funeral was a precursor to the public obsession with movie stars.”

New York’s pioneering tabloids, not least of all the Graphic, supercharged that obsession with their emphasis on big personalities. As the journalism historian Andie Tucher once told me, “Modern celebrity culture was essentially born in this era.”

In the end, the Graphic didn’t outlive Valentino by very long. Despite its circulation-busting coverage of his death, it never managed to catch up to the Mirror and the News. In 1932, the Graphic became the first casualty of the tabloid wars when Macfadden, saddled with millions of dollars in libel expenses, was forced to shut it down.

Macfadden, for his part, did eventually run for president. And for U.S. Senate. And for mayor of New York. But the publisher’s far-fetched political career was not to be. He died in 1955 at the age of 85, after refusing medical treatment for a case of jaundice that he’d aggravated by undertaking a three-day fast. You can find traces of him not only in modern tabloid pirates like Murdoch, Harvey Levin and David Pecker, but in the brand of vulgar, publicity-seeking quackery that Macfadden pioneered. (Haitians eating pets, anyone? Or water turning kids gay?)

Though largely lost to time, the Graphic’s influence on celebrity media is undeniable. Walter Winchell, after jump-starting his career as the Graphic’s man on Broadway, defected in 1929 to the Hearst empire, where he rose to national prominence as a syndicated columnist who would become, arguably, the most famous celebrity gossipmonger of the 20th century.

In the early 1950s, Winchell gave valuable publicity to a new magazine called Confidential, founded by his former Graphic colleague Robert Harrison. Influenced by his formative experiences at the Graphic, Harrison saw an opportunity in the public’s growing appetite for “learning of the inside about other people with whom they were familiar because they may have seen their pictures in the paper, or in the newsreels. There was excitement and interest in the lives of people in the headlines and getting behind the story.”

Confidential’s heyday as a pioneering Hollywood scandal sheet lasted only a few years. It’s part of a throughline that began with the Graphic’s zany Valentino crusade and continues today with the clickbait of TMZ, the Daily Mail — and any number of other mass-market publications or Instagram accounts that prey on our fascination with the famous.

As Macfadden astutely recognized when he launched the Graphic a century ago, “You have to know how to cater to the public to whom you appeal. You have to know what they want to read.” Even if seeing wasn’t believing.

A note on sources:

Archival issues of the Evening Graphic, the Daily News, and the Daily Mirror were indispensable, as were the following books: Sauce for the Gander, by Frank Mallen (1954); The New York Graphic: the Worlds Zaniest Newspaper, by Lester Cohen (1964); My Last Million Readers, by Emile Gauvreau (1941); Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity, by Neal Gabler (1994); and Shocking True Story: The Rise and Fall of Confidential, “America's Most Scandalous Scandal Magazine,” by Henry E. Scott. I drew on key material from the archives of Joseph Medill Patterson (Lake Forest College), the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, Editor & Publisher, Time, The New Yorker and The Nation. Other sources include The Purple Decades: A Reader, by Tom Wolfe; the New York Public Library blog; Vanity Fair; The New York Times; Getty Images; British Pathé/Reuters newsreel; and the Press of Atlantic City.

To give you a sense of how rare it is to find original copies of the Evening Graphic, consider that when I was researching my book about the Hall-Mills murders and the birth of America’s tabloid press, the New York Public Library informed me that its microfilm of the Graphic did not include the key years 1924 to 1928. After the publication of my book in 2022, a woman came forward with an enormous archive from the Hall-Mills case. The priceless trove of primary-source material — now housed at the New Brunswick Public Library in central New Jersey — includes a bound volume of the Graphic from the summer of 1926, when news of the Hall-Mills murders and the death of Valentino simultaneously filled the tabloid each day. This article includes information from and photos of those priceless pages. The images of the composographs, now in the public domain, were originally republished in Mallen’s Sauce for the Gander.