Plague It As It Lays

What We COVID For Love

Anyone having one of those weeks?

First of all, apologies for this sporadic COVID publishing schedule. Still finding our sea legs in the work/quarantining/home school balance. Fortunately, we've still got oceans of time to figure that out!

But with nothing much on our minds apart from contemplating bleakness, despair, and ultimately, the abyss, it's hard not to think about, when the rubble clears, what's going to be left of this place? Or more to the point, what gets brought back?

You can't shut down an industry—the film industry, that is—for the better part of a year and think the show's going to go on like nothing ever happened once the whistle blows. Especially when it was an industry already facing an existential, if not crisis, then a nervous breakdown at the very least.

Complicating the question is that film is not a standalone industry; it's an arm (and not generally the healthiest arm) of a handful of media conglomerates. For those conglomerates, the theatrical sideshow is increasingly beside the point to their great concern, ie, The Great Streaming War, in support of which they have been mortgaging their companies' entire futures. Twas a time when a division could go about its work as a nice little healthy, or hopefully not that unhealthy, business. But now when everyone is playing for all the marbles in the Great Entertainment Semi-Finals, no division can be a bystander.

The appointment of Jason Kilar last week to oversee WarnerMedia, including the studio, should show how the tide has turned. All of the legacy studios are now overseen by execs from the TV world, with the exception of Disney where Bob II's background is from theme parks and operations, following Bob I, whose background was in TV.

(Kilar is only ostensibly a TV guy. Really he oversaw the early days of the industry's first effort to resist Netflix and YouTube and has more or less been in the wilderness for the last seven years, which might as well be one thousand now. Before Hulu, he was an Amazon executive. He's the kind of data quant increasingly running corporate America.)

Viewed from outer space, the implications of this moment should be clear, and the transition easy. Movies have been struggling in all sorts of ways—artistically and commercially—and are now . . . gone. TV, meanwhile, has never been better—creatively or audience-wise (unless you're a legacy broadcast network). So move the pieces from Column A to Column B, right? Which is what a lot of people seem to be suggesting is the sensible approach for Hollywood in this calamity.

Problem is that as much as we would love to say–It's all content! Give the viewers what they want, when they want it and stop being so goddamn fussy!–theatrical and streaming remain different businesses with different needs.

The emergency VOD releases will bring in a trickle of cash flow at a time when the companies are happy to get what they can, feeding a captive worldwide audience at this moment. But there is nothing in the history of streaming offerings to suggest that these regularly, if ever, bring any kind of revenue to rival what even a middling theatrical release can do.

Netflix has been doing its 500 film experiment with, essentially movies of the week, and those seem to do for them what MOW's have done for TV networks since the 1970's—a little uptick in viewers, a little buzz, if you're lucky an award or two, a little service to your core audiences; but generally ephemeral results. I'm sure someone at The Service has a printout showing that the returns on Spenser Confidential are way up in John Wick territory. In fact, a week ago The Service doled out to the media that the Wahlberg reboot of the detective garnered 1.25 billion viewer minutes, a new yet still incomprehensible statistic that means nothing.

I'll believe that when I see the fine print. What I still haven't seen a streaming movie do, however, is strike a motherlode of IP that can fuel not only box office, but games, toys, and rides for decades to come.

Movies will come back in some form. Somehow or another, at some point somewhere down the line. Just like restaurants and parks and manicurists will come back. Movies are part of the firmament fulfilling a basic need: a place to go.

That is a need that will be at a premium when the corner is turned. As terrifying as it is to think of inching back into a crowded place at this moment, once people feel confident that they can move around without being struck down, once—eventually, someday—when testing becomes regular. (AMC and Disney have both suggested temperature screenings in the future, a future I find both reassuring and horrific.) As much as we've all loved getting a chance to catch up on every show anyone ever told us that we should watch, once we feel safe leaving the house, people aren't going to want to see their living rooms again for years. I can picture a massive couch burning to celebrate finally getting the hell back into the streets. If you think people are going to remember this as a golden time when they could do nothing but watch TV for five months and say—sign me up for a lifetime of that!–you've got a different read on the mood than I do.

But even if movies as a destination and pillar of the culture survive, it's less clear what the industry that makes them looks like when the trumpets sound. Shutting down the entire operation for months, both production and distribution, is not helping anyone's balance sheets, many of which were none too solid to start with. Remember the days when Sony was demanding that Tom increase the film division's profits to 10%? And that seemed impossible then?

Any model you've got for some kind of business in entertainment demands a fairly high degree of insanity and a fairly high appetite for loss, which in this industry is always coupled with its partner, public humiliation. No sane company that cared about its money would go into a business where you are forced to constantly make massive bets on completely unknown products which either connect or don't based on intangibles that even after the disaster, people can't quite describe.

Which is why it's a good thing that entertainment such a glamorous and desirable place to be so we don't have to depend on finding sane tycoons or companies. Given that public connection is based on so many intangibles, a lot of balance-sheet craziness can be shoved under that heading.

But even so, such a huge swath of this business operates in ways that give self-serving and insular a bad name. The MeToo revelations are the most obvious example of something that in a "normal" world would've ended long ago but lived on under the guise of artistic privilege.

What we're seeing now are the things that made basic sense scrambling to stay alive, and the things that were a stretch on a good day starting to fall by the wayside. Some kind of Hollywood will rise again, but when it does, the blind eyes and bottomless pockets that defined people's approach to our business are going to be gone. We'll rebuild with a more hardened, cynical outlook—and a tighter budget.

In a lot of ways, maybe the Hollywood of the future looks a lot more like the Hollywood of yesterday: a simpler business of making entertainment, minus about 100 layers of insanity and self-dealing. If you want a harbinger of the future, CBS announcing the return of the Sunday Night Movie sums it all up.

What comes back and what doesn't? These past weeks are seeing so many things that were unworkable to start with melt away.

Julie Andrews Sings Try To Remember

Some of the places where the ground is shifting beneath our feet, as of this writing:

• MEGA-AGENCIES.

Ari nearly did it. A couple of lucky breaks last year, had it not been for the IPO bust and then, live entertainment being wiped off the face of the earth, he might've pulled it off.

But it was always a stretch. The idea that a talent agency would be the hub of a larger media company is an interesting notion, but the conflicts inherent in that could never quite be waved away.

Nor could one just dismiss the reason that since time immemorial agencies have failed to transform themselves into bigger businesses: Whatever you put around a talent agency, at its core it is a business of relationships, where the talent walks out the door every night, as it's said.

The evolution of agencies since the 80's, from relatively modest firms serving the industry's talent to these behemoths looming down over mere talent, has long seemed to be about embracing all the trappings and accouterments of the global elite for themselves. I've shown this series of images before, but they speak louder than words about the growth of agency headquarters from the modest William Morris quarters on El Camino

to Mike Ovitz's IM Pei fortress

to today's CAA hulking glass Leviathan

or to Ari and Patrick's golf-course equipped imperial suite, to name another example.

It was all well and good when the money was sloshing around the business faster than anyone could count it, but the music has stopped and everyone is looking to grab a chair, with the goliaths having a mountain of overhead to cover every month.

Defections and rumors of defections are in the wind, with WME in the most precarious spot. Post-failed IPO, will everyone there accept the pay reductions and move forward? How much of the leadership team survives?

Or does this ultimately give them an excuse to get back to prelapsarian basics, sell off the divisions and get back to being just an agency, as they did pretty well before they started this whole ride?

• THE END OF THE 90's

There are going to be movies, so there's going to be studios. But how many, owned by whom, and for what purpose remain open questions.

If some or all of the studios come out of this in or near insolvency or fire-sale condition, Apple and Amazon are the obvious white knights/grave robbers as the long-forecasted consolidation is quickly thrust upon us.

If you want to game it out, say, for the sake of argument we come out of this with four studios: AT&T, Comcast, Apple/Disney, and Amazon, with everyone else—including Netflix—folded into one of the above, take your pick.

First question: How long do Apple and Amazon tolerate the high overhead/low margin/data-poor theatrical business? (Rough draft answer: until their first really bad summer.) You can argue all you want that it's a good business to be in, but it's also such a tiny trickle of profits in their larger balance sheet as to be meaningless. If the window, in particular, is competing with their all-digital, data-rich, dear-to-their-heart streaming future, then who needs that?

Second question: If Amazon and Apple aren't committed to theatrical, are Comcast and the phone company going to be?

Third question: When you've got to take everything from zero again, how much of what was there are you going to want to bring back? Development has to continue if you're going to keep making movies, and indeed, it's still going full steam now from all I hear. One thing we were already edging towards was the end of the Big IP era. Disney and Marvel were already turning to the back pages of their catalog for their next generation of hits. For everyone else, the basket of easy home runs has been plucked bare. Which is going to mean . . . more scripts, more pitches, more development. And probably, more power to stars if the title can no longer carry the weight alone.

Beyond that: Production is production. But how much of the marketing and distribution infrastructure if you're at zero-based budgeting would you need to rebuild? Do you really have to buy $50 million in TV ads for every production? Spend tens of millions flying casts to festivals around the world? Jet tickets for entourages of a thousand? Hush money for enough former employees to man an aircraft carrier?

Even if we could still afford these things, which we can't, pointing a firehose of money at any hanger-on who makes it through the company gates is not exactly the tech-world way, to say the least. So much of Hollywood still functions like the world is safe and unchanging and Bob and Terry are still running things, handing out the keys to the jet to all their very best friends. That potent mix of complacency and entitlement is in for a rude awakening.

• The Golden Arches

The Imagine debacle is going to go down in history as the Bastille Day of celebrity culture. It didn't come out of nowhere.

The moment when social media existed to rubber-heart and every flutter of celeb-dom has long passed. The moment it erupted to rip to shreds an actress for daring to sing an uplifting song with her friends, a rubicon was crossed.

The early social era allowed the stars to position themselves as everyone's Big Cool Friend; not aloof and remote like the glamour icons of yore but over-sharingly human and omnipresent and willing to share glimpses of their private-jet, infinity-pool lifestyles with their fans, because it was aspirational, bringing their fans along for their amazing journey.

Somehow, along the way, our grandees—always eager to have their cake and let them eat it, too—thought that aspirational excitement applied to them. The paradox of Hollywood liberals who flaunted their ever more fantastic trappings of wealth has been insupportable for a while now, even as life became increasingly difficult for the middle and lower ranks of their industry and town.

Well, the wolves are sneering at the door now. David Geffen may not have anything to lose at this point, but for anyone who isn't planning to spend the rest of their life at sea, this little valentine should represent the point when the public stopped being amused. At all.

Meanwhile, I hear tales these days of poobahs sending their housekeepers for private COVID tests administered by Westside concierge doctors.

There's a lot of gasoline on the floor right now, and if folks want to throw matches at it, don't be surprised by how that goes.

But I think people are going to find that token nods in the right direction and the right lapel pin on the red carpet are going to be seen as much more the problem than the solution in the era upon us.

• Trade-Offs

I thought I was beyond the capacity to be surprised by any level of casual corruption in the world of industry coverage, but the emails laid outin this Daily Beast piecebetween Matt Belloni, the serious and menschy outgoing editor of THR, and his corporate overlords are enough to curdle the blood of even a vampiric cynic like me.

That an executive could preside over an instrument of journalism and write the sentence "Not sure you can see the coverage that took away from a great moment for Reese" is another milestone in the death of the free press in this country.

However! One can certainly see how she would make that mistake. The rapturous intertwining of the covered and the coverers over exclusives, panels, cover shoots, announcements, leaks, junkets, set visits, premiere tickets, screening events, and on and on and on, certainly make it seem to the naked eye like they're all partners in one big high-school musical.

This may not be direct COVID fall-out, but it's another example of how in stressful times–and the times are about to get a lot more stressful for the media–basic cracks are revealed. Kudos to Belloni for making this stand on principle. When's the last time you heard of anyone in Hollywood risking their job for something like that, on either side of the coverage divide?

Lord knows who they'll be able to get to take the reins with this out there.

• Pay Offs Again

This is also not directly COVID related, but in the spirit of things, you also can't imagine something like the Ianniello goodbye elbow bump crossing the river Jordan. Even by the very high bar of bonkers Hollywood golden parachutes,$125 million for Joe Ianniello to not workat ViacomCBS is impressive.

That's $125 million for the man who was Les Moonves' bean counter, and for a few brief months, the caretaker of CBS.

To put that in perspective again, Christine McCarthy, CFO of Disney and a larger, more complex and vastly more successful company than CBS,was paid just shy of $14 million last year.

So Joe Ianniello was paid 9 years of his Disney counterpart's pay to go away.

I know contract and all that, but one can only presume that Redstone, Bakish, and the board members who approved this all along the way must've had very good reasons for wanting to keep Joe happy. And I would feel like saying something like that was closer to wanton callous speculation if the accounting of the sins of the Moonves era had ever been publicly disclosed as promised.

How are these days going for you? What are you hearing on the streets during these times? What’s going to be left when they open the gates again? Share your tales of woe, heartache and redemption in the comments and let’s keep in touch!

ELSEWHERE IN CORONAWOOD

• Hollywood always provides plenty of examples of grotesque entitlement, but in times of crisis, it can be impressively quick to open its wallet and give its time. Some examples far and wide:

• Many of our top poohbahs have stepped up to support the LA Mayor’s Fund which has raised money to support front line medical workers and give help to those facing extreme hardship during these days. Donate here.

• Matthew McConaughey hosts bingo night for elderly isolating Texans.

• Tyler Perry covers everyone’s bill at Winn-Dixie.

• Silver Lining: Los Angeles air now the cleanest of any major city on earth.

• John Krasinski’s Some Good News is one of the great public services of Hollywood history. If you have children you need to watch the last episode with them. Do it now.

• Here by the way are a couple of excellent compendium of links for home school, and staying sane with your family ideas and resources. The stuff on these lists has saved my life over the past month.

• Terry Teachout’s joyous songs collection.

Let’s be safe out there everyone please! And keep in touch! Drop me a line or say hi in the comments!

If you’re just receiving this edition of The Ankler from a friend, press below to subscribe. You never know who’ll be in The Ankler Hot Seat tomorrow…

The Ankler’s Got People Talking!!

In Variety on THR

In Playboy on the Me Too legacy

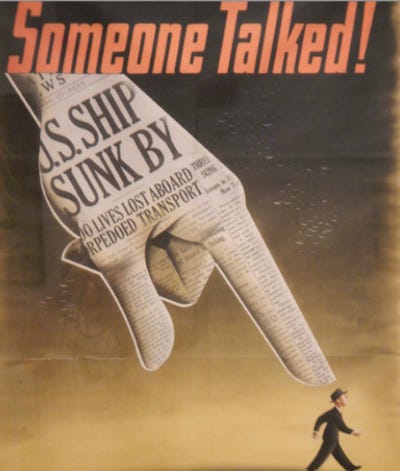

IF YOU SEE SOMETHING, SAY SOMETHING The Ankler looks to you! to help us be the eyes and ears of this great industry! Got a crazy email from your boss? See a major poobah have a meltdown in the commissary (or forget to tip)? Just had the worst story notes meeting of your career? Heard a rumor that the Big Guy is packing his office? Did they change the name of a conference room on your hall? As in all detective work, no tip is too small. Help The Ankler tell the world. . Send your tips to richard@theankler.com or, with end-to-end encryption on whatsapp and Signal. (Msg me for the number). And of course, ping me on gchat at richardrushfield anytime day or night. Confidentiality guaranteed on pain of death.

EDITORIAL POLICY: If you have been the subject of a piece on the Ankler and you would like to respond, the Ankler will be delighted to print your reply in full. Please send your response to richard@theankler.com

If you are interested in advertising on the Ankler: write us at ads@theankler.com for rates and info.

The Ankler is Hollywood’s favorite secret newsletter; an independent voice holding the industry’s feet to the fire. If you’re a subscriber, feel free to share this edition with a friend but just a couple, please. The Ankler depends on its paid subscribers to keep publishing.

If you’ve been passed along this issue, take the hint and get on the train. Find out what everyone’s whispering about! Subscribe now!

And if you enjoyed this issue, feel free to press the little heart down below, which helps alert others to the wonders of The Ankler.