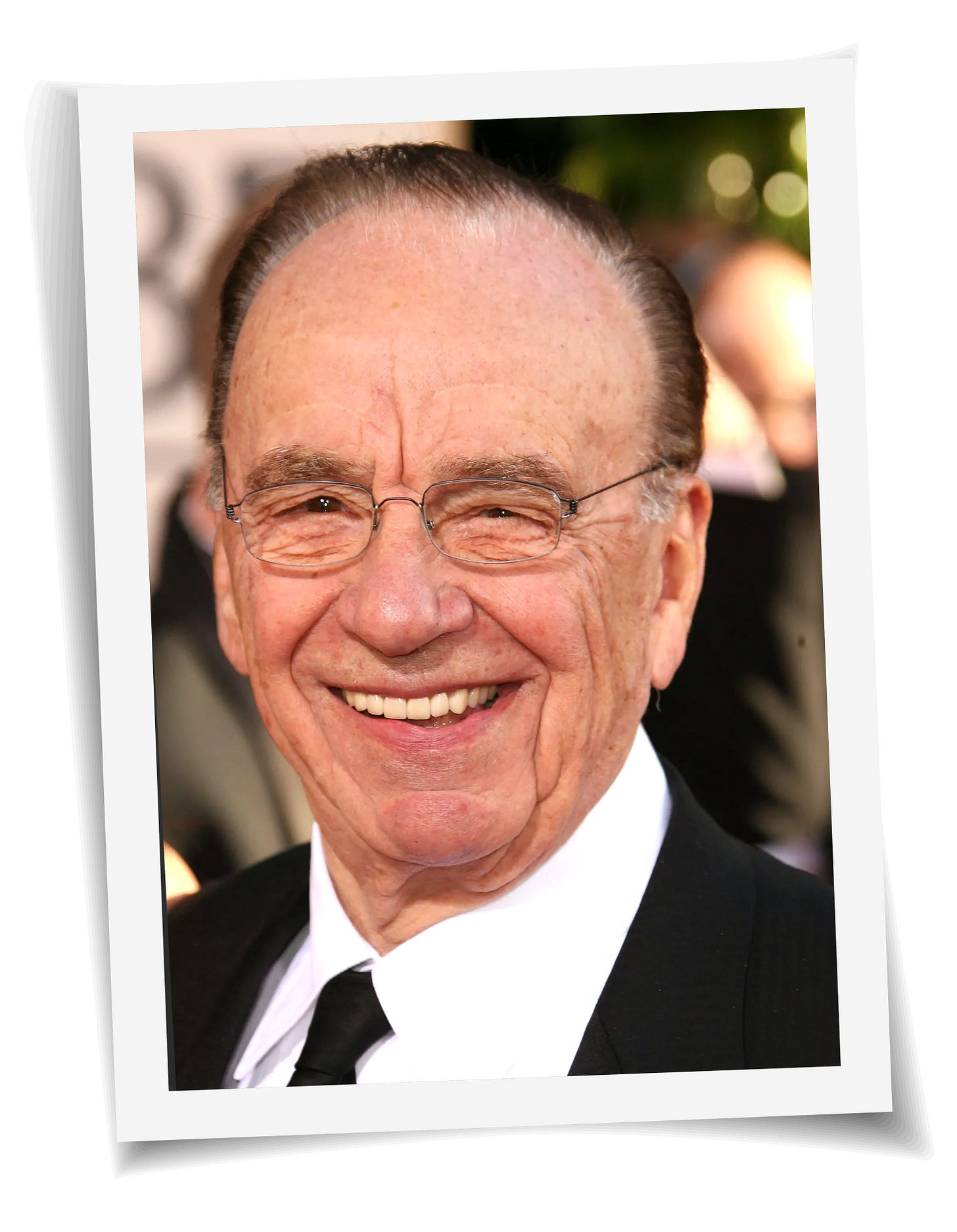

Michael Wolff Excerpt: Rupert Murdoch's Family Drama, Brilliance and Brutality

The mogul's 'obituary' opens the buzzy upcoming book, 'The End: The Fall of Fox News and the Murdoch Dynasty'

“Michael Wolff’s books were my foundation and port of entry for working on Succession.” So said actor Jeremy Strong (Kendall Roy).

Now, with news arriving that 92-year-old Rupert Murdoch is stepping down as Chairman of 21st Century Fox and News Corp. just days before publication of Michael Wolff's revelatory new book, The Fall: The End of Fox News and the Murdoch Dynasty, no one but Wolff better tells the story of Murdoch and his place in the media firmament (infamously, Wolff had unprecedented access to Murdoch and his family, even his mother, for the 2008 biography The Man Who Owns the News: Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch before the billionaire cut him off).

In the book’s first chapter, Wolff, author also of the #1 New York Times bestseller Fire & Fury, imagines an eventual obituary of Murdoch. It's an insightful overview of the news magnate’s life and career — pulling no punches — and an entry point into the sprawling impact of one singular man.

Keith Rupert Murdoch

1931–202_

In newsrooms around the world — and Rupert Murdoch controlled more of them than anyone else ever has — the common practice is to write advance obituaries for the great and good and the notably mendacious and vile. The obit is put in the “can,” all but finished save for a last-minute update and the final details. While this one would likely not be among those under lock and key and special passwords at Murdoch’s own newspapers, here is a summation of one of the most consequential lives, for better or worse, of our time — with its end presaging one more of the kind of dramatic business and political developments that he caused throughout his long career.

Keith Rupert Murdoch, who revolutionized the media industry in his seventy-year career, has died at the age of __ , a spokesperson for his family confirmed.

It was a life of stark contradictions, an example of will and denial, purpose over nature, for this heir to generations of Calvinist clergymen.

The sharpest negation of self might be that the mogul’s paramount legacy was a business, Fox News, he had little to do with and often contempt for, and a president, Donald J. Trump, who he regarded as a “fucking idiot,” who his news network had been instrumental in electing.

He was an Australian princeling, a child of one of the most vaunted and privileged families in his country, who became a publisher of working-class, down-market newspapers. He was a personal prude, an upright Presbyterian, who blew up the British publishing world with his pictures of bare-breasted girls on Page 3 of The Sun newspaper, transforming it into Britain’s largest-selling paper. He was a dedicated newspaperman, perhaps the last on earth, in love with his newsrooms and his presses, whose real fortune would be made from television that he didn’t watch and movies that he didn’t see, in a Hollywood that he disdained (and that disdained him). He was the consummate tabloid newspaper publisher — the rougher, tougher, crueler, more sneering his papers were, the better — who believed there was no reason he could not also run the world’s most respected newspapers, acquiring the London Times in 1981, and the Wall Street Journal in 2007. He was among the men who defined the model of modern business ruthlessness and unsentimental bottom-line sensibility, but his biggest dream was to pass his company to his children, no matter how unprepared or unworthy or fractious they might be.

He was born in 1931 into a near-Victorian world. His parents, Sir Keith Murdoch and Dame Elisabeth Murdoch, both children of upper-class nineteenth-century Scottish immigrants, were of an elite circle more attached to high British culture than egalitarian Australia. His father, by temperament cold and withholding, and Rupert, resentful and rebellious, remained at continuous odds. Keith Murdoch sent a series of emissaries to his son at Oxford, where he was in school after the end of the second World War, to reprimand him for his spending, idleness, and flirtation with left-wing ideas. Nor was his relationship with his mother, who lived to 103, all that much more congenial. He faulted her for poorly handling the estate when his father died in 1952 and hobbling his inheritance.

Perhaps it was the disdain he harbored toward his own father’s business acumen that explained the ferocity and single-mindedness that would make him among the most transformative global business minds of the era. Keith Murdoch was the chairman of the Herald and Weekly Times, one of Australia’s largest media concerns, but not its owner and was ultimately kicked out of the company he built by men with greater ownership stakes. Lesson learned: control is everything. (The son would later buy the company that had fired his father.) Another lesson he learned growing up in Australia’s small circle of power that often gathered at his parents’ table: power is an insider’s game. To gain it, he learned from his own days as an interloper publisher, beginning with the single paper his father left him in Adelaide, an outsider must replace the insiders.

His goal was clear: global power. His method, without much capital, hardly any organization, nor significant connections beyond Australia, he had to invent. Newspapers he understood were a sure route to influence and power — many newspapers meant more influence and power. Here began his historic arc of often predatory acquisitions. He expanded his business from Australia to the U.K. by astutely playing, if not tricking, the family that owned the down-on-its-heels British tabloid the News of the World, followed shortly by using similar backdoor tactics to acquire the beleaguered Sun. With a down-market plunge to new levels of tabloid scandal and outrage, he turned both papers into industry phenomena. He was promptly nicknamed by the British satirical publication Private Eye, with arch disparagement, “the Dirty Digger,” for his Australian roots, his Page 3 girls, and the scandals his papers unearthed. The name stuck for quite some decades. After his move into London, there followed his acquisition in the U.S. of a paper in San Antonio, Texas (for no clear reason, other than that he could afford it), then the New York Post, the bottom-rung paper in New York, and simply because they were available, New York magazine and the Village Voice, and then the down-market papers in Boston and Chicago.

He sought always to turn his business power into political power. He was responsible for a succession of Australian prime ministers. In Britain, he was a pivotal supporter of Margaret Thatcher; the Sun’s switch to supporting Labour was among the significant factors in the election of Tony Blair. Within months of his takeover of the New York Post, he made it the paper’s mission to elect Ed Koch the mayor of New York in 1978, and succeeded, a precursor to his dream of electing an American president.

But the real transformation for him and for the media world, and ultimately for American politics, came in 1985 with his agreement to buy the movie studio, Twentieth Century Fox. Up until this moment, the media business was firmly compartmentalized: publishing, television, movies, radio, books and the nascent home video and cable business, all finely — vertically — segmented by different corporate owners. But, suddenly, Murdoch was a publisher with a movie studio. Then, vastly overextending himself, Murdoch became not just the only publisher with a movie studio but, in a further deal, his movie studio became the only one that owned television stations. Following Murdoch’s example, Time Inc. shortly merged with Warner Communications; Viacom bought Paramount, adding on CBS a few years later; and Disney snapped up ABC. Hundreds of independent media companies were soon reduced to a handful.

Next, Murdoch decided to try to break through another media wall: he would launch a fourth U.S. television network. Using his television stations, and with Barry Diller, an upstart television and movie executive running the company —and with the hit show Married . . . with Children, a breakthrough sitcom on the biliousness, rather than television’s usual idealization, of American family life —the Fox Network was soon a ratings competitor against ABC, NBC and CBS. Murdoch was now the most important figure in the American media business, and, aggressive in his conservative views, a political power in the land.

His personal center of gravity stayed in the newspaper business. He was at home in a newsroom in a way that he could never settle into on a movie lot, where executives strove to keep him out of meetings with directors and stars whose costs and conceits he had little patience for. As he created the modern, cross-platform, media megalith, he remained, for the ever-cooler media kids, the scowling old guy, his singlet visible under his white shirt, only truly happy studying a front page.

He wanted CNN. But his move was rebuffed — he was still looked down on as “the Dirty Digger” — and CNN was sold to Time Warner, the five-year-old conglomerate that was now the biggest power in media. His response was simple: he’d start his own around-the-clock cable news station.

In the late 1980s, like much of the business community Murdoch, too, was in a state of financial delirium. Making acquisitions in Australia, Britain and the U.S., he was in an almost constant state of flight and jet lag. By the end of the decade, he had added to his publishing-movie- and-television empire, two book publishers, Harper in the U.S., and Collins in the U.K., creating one of the world’s largest publishing houses, assembled a major magazine publishing group, acquired a controlling interest in Britain’s vast and money-losing satellite television company, BSkyB, and for no clear purposes, an airline in Australia.

But then the financial crisis in the media business of the early 1990s all but bankrupted him. At any point in a six-month period of negotiating with his creditors, he was days or hours away from losing his business. It is certainly among his greatest achievements — one of stamina, and humility — that he did not.

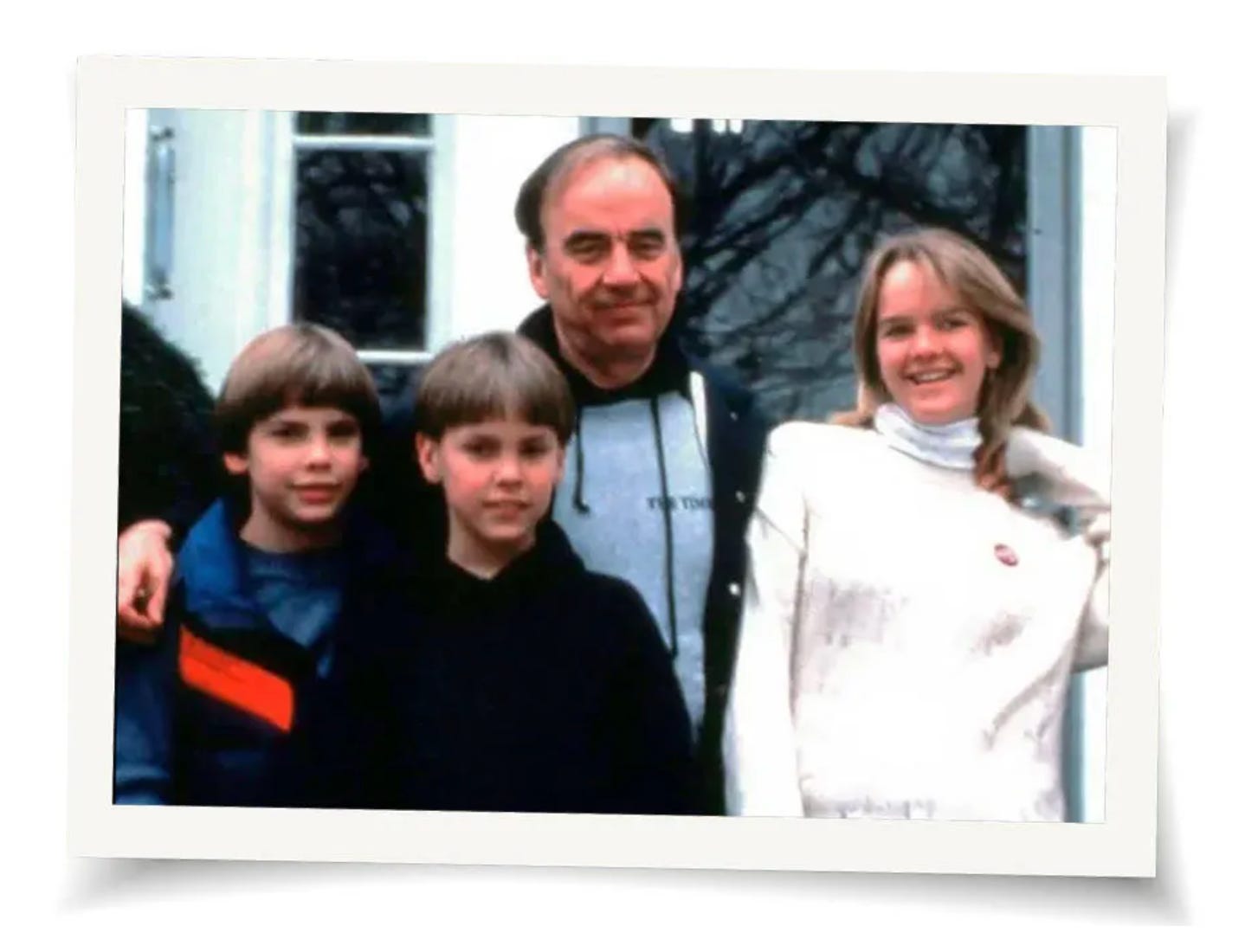

He regrouped in California. These were unhappy, wilderness years. He was ill-suited to a daily dose of the entertainment business. He had promised his wife — his second wife, Anna, the mother of three of his children, who he had married in 1967 — that, if his company survived his financial undoing, he would turn it over to others to run and, as he approached sixty-five, start to wind down for their retirement together. But he chafed under this pledge, as his wife sourly tried to hold him to it. Evenings found him buttonholing his executives as he sought company for lonely dinners in the Fox commissary. He wanted to get back to news and away from entertainment. He wanted a 24/7 cable news network. He wanted CNN. But his move was rebuffed — he was still looked down on as “the Dirty Digger” — and CNN was sold to Time Warner, the five-year-old conglomerate that was now the biggest power in media. His response was simple: he’d start his own around-the-clock cable news station.

Roger Ailes, a television executive, and former Republican political operative, unhappily employed at NBC, to whom Murdoch offered the job of starting a cable news station from the ground up, was firm in his conviction that he could create an upstart news channel and do it within the bounds of the money Murdoch was willing to spend.

Fox News launched in 1996. Staying within budget, and then beating early projections, meant Ailes encountered little oversight from his boss.

Murdoch had more pressing concerns: he was in love. At the age of sixty-five, this most cold and impersonal of men, married for three decades, with four adult children, met a junior staffer — an intern on a work break from business school — at his company’s outpost in Hong Kong. Wendi Deng, daughter of a provincial couple in post–Cultural Revolution China, was twenty-nine when she met Murdoch.

Murdoch’s natural and careful outward countenance was formal and puritanical. He took great pains to publicly end his marriage with his wife Anna before revealing any hint that his affair with Wendi had begun. The announcement of the split startled the Murdoch world. But not even his closest circle suspected that he might have a girlfriend. Two months after the split, he called his daughter Prudence [from Murdoch’s marriage to first wife, Patricia Booker] in Australia and said he had met “a nice Chinese lady.” Making a whooping sound of astonishment, she ran upstairs in her family’s home in Sydney, shouting to her husband, “You won’t believe it!”

The Murdochs were residents of California, a community property state. A division of his assets might easily have sundered his company, or at least his control over it. But Anna hobbled him in a different way. Instead of the billions she might have extracted, she agreed to a settlement of $100 million, conditioned on freezing his assets in a trust for his four children, with each receiving one vote, and precluding any “issue” that might follow from any new relationship from participating in the trust. Such was the structure that would dog him until his death — and after.

The early years of his marriage to Wendi, with, in quick succession, the birth of two daughters, Grace and Chloe, were something of a constant negotiation between his new life and old. With his daughter Elisabeth furious about his divorce, not speaking to him, he bound his sons to him with outsize authority in his company. His older son, Lachlan, was installed in the office next to him in New York. His younger son, James, became the company’s de facto transformation agent, overseeing News Corp’s manic pace of digital investments.

Murdoch was negotiating between old family and new, but also negotiating between his executives and his children.

Fox News had quite unexpectedly, and on the cheap, with its big blondes, and emphasis on talk radio–type broadcasters, become the number one and most profitable cable news station in America. By 2005, Fox was a brand name greater than Murdoch’s own. Ailes had achieved a success in the company great enough and specific enough to make him one of the few executives in Murdoch’s long history that would cost Murdoch too much to replace. A schemer and plotter, Ailes focused much of his ever-boiling resentments on Murdoch’s children and the power Murdoch was extending to them. Elisabeth (Vassar), Lachlan (Princeton), and James (Harvard), he correctly saw as East Coast Ivy yuppies. Lachlan and James were gay, he whispered — this became nearly gospel within Fox News — and Elisabeth, a drug addict who hosted sex parties. He had proof, he maintained. In 2005, in a showdown with Lachlan over the son’s push for more authority, Ailes rushed to Murdoch and issued an ultimatum: him or me. Murdoch chose Ailes. Lachlan, in a huff, packed up and moved his family back to Australia.

This left James as the heir. He had been sent to run the struggling U.K. satellite television company BSkyB — now known as Sky — and then was elevated to running all Murdoch operations in Europe.

In 2007, in what now appears to be the last moment of belief in a credible future for newspapers, Murdoch realized a near lifelong dream of acquiring one of the world’s two most authoritative papers: the Wall Street Journal (the New York Times remained out of his grasp). Here was, in Murdoch’s mind, the capstone of his career. But in many ways the most tempestuous part of it had just begun. Within months the global financial crisis descended, dooming the newspaper business. The election of Barack Obama, supported by all the Murdoch children, and, indeed, a reluctant Rupert, had suddenly turned Fox News from what could yet be regarded as a gadfly, tabloid, right-leaning voice, into something more evidently virulent, truthless and racist — ever more popular and profitable for it — earning the enmity of his cosmopolitan and elitist children.

Then, just as Murdoch was closing in on his goal of acquiring the 61 percent of Sky that was owned by public shareholders, which would firmly establish both his company’s global reach and its status as the world’s largest media enterprise, scandal struck.

Reporters at two of Murdoch’s London papers, the News of the World and the Sun had been systematically hacking into the voice mail of celebrities, sports stars, and royals, with at least the tacit awareness of James Murdoch, and, quite likely, his involvement in a subsequent cover-up. Compelled to acknowledge this as the lowest public moment of his career, a befuddled-seeming Murdoch, with James beside him, was forced to testify in a televised hearing before a Parliamentary Select Committee. Barely escaping prosecution, James was secreted out of the U.K. and back to the U.S. Murdoch was forced to close the News of the World. The Sky deal was scuttled by regulators who formally deemed Murdoch “not a fit person” to own a major British company. And shareholders would soon push Murdoch to sequester his beloved but tainted newspapers into their own entity, divorced from Twenty- First Century Fox. Murdoch still controlled both companies, but the larger statement was clear: nobody wanted the newspapers that Murdoch cherished.

And then, finally, Murdoch’s marriage to Wendi Deng, long unwinding, came undone with company sources leaking news of his wife’s affair with former U.K. prime minister Tony Blair.

Nevertheless, the eighty-three-year-old Murdoch, battered by events of his own making, set out with absolute determination not to change direction.

Having sidelined the two executives, Peter Chernin and Chase Carey, most responsible for turning his company into a well-managed, modern enterprise favored by Wall Street, he then issued an ultimatum to his son Lachlan after his nearly ten years of idleness in Australia: if he had any hope of a leadership role in the company, it was now or never, or else James, however recently disgraced, would be appointed CEO. In 2014, Lachlan and his family returned from Australia and he and his brother became co-CEOs in a primal bake-off.

But, if Chernin and Carey had been taken out of the game, Ailes had not. Ailes’s toxicity and enmity toward his new nominal bosses was one of the few things the brothers — James largely in New York, Lachlan in L.A., hardly talking to each other — could agree on: it was either them or him.

In July 2016, Murdoch was on an extended honeymoon with his new wife, the 1970s top model, longtime former partner of Mick Jagger, and rock-and-roll society fixture Jerry Hall. At that moment, a sexual harassment suit was launched against Ailes by a former anchor, Gretchen Carlson. Ailes believed it was instigated by the brothers, exactly timed for their father’s absence. They acted immediately and in concert, mobilizing the company and its lawyers against Ailes and largely leaving their father in the dark. Two weeks later, the first major take-down in the yet unnamed #MeToo movement was a fait accompli, and Ailes, after twenty years as the Fox heart and soul, was ignominiously cast out.

This precipitated a ferocious battle between Lachlan and James for control of Fox News. Fox’s unresolved future, combined with the wholly unexpected election of Donald Trump and recent notice that the final effort to buy Sky would not receive the necessary approval in the U.K., left the company in perhaps the greatest existential state it had ever known.

Ailes’s toxicity and enmity toward his new nominal bosses was one of the few things the brothers — James largely in New York, Lachlan in L.A., hardly talking to each other — could agree on: it was either them or him.

In 2017, in a deal shepherded by James, and hotly resisted by Lachlan, Twenty-First Century Fox accepted a $71 billion offer from Disney for the lion’s share of its assets, leaving behind only properties Disney could not take for regulatory reasons and Fox News, which it did not want. Each of the six Murdoch children received a $2 billion disbursement. James walked away from further responsibility for the company’s remaining assets — most notably Fox News. Lachlan’s consolation prize was the reins of the diminished enterprise.

Fox had become, since Trump’s election, even more successful. It had not only survived the loss of Ailes — who died in his Palm Beach exile in the spring of 2017— but the loss of its ratings leader Bill O’Reilly in a further sexual harassment scandal and of Megyn Kelly, the anchor who the Murdochs had hoped might lead the network to a not-so-right-wing future. Instead, Trump was now its star. Sean Hannity, the longtime prime-time ratings laggard revived his career with an unquestioning devotion to Trump — making himself, to boot, one of Trump’s leading inner circle advisers. Tucker Carlson, given an anchor slot because the Murdochs believed he was a more moderate Republican, overnight became a firebrand of the new Trump order and cable television’s ratings winner.

Despite the Murdochs’ tentative efforts to moderate their news network’s worst excesses, Fox morphed into something close to an arm of the Trump administration. The irony cut deep: Murdoch had long used his media power to make and break politicians, now he was helpless to control the supplication by the most powerful news outlet he had ever owned to the belligerent president. The money was just too great.

This left father and son, Rupert and Lachlan, in their own estimation, as nearly martyrs, bearing the pain of Fox in order to preserve its value. Lachlan found himself all but ostracized in liberal Los Angeles. Rupert found his happy life with his new wife, Jerry Hall, increasingly strained amid her entertainment, art, and fashion social set, and their open antipathy, and often anger, toward Fox and Trump — and him. In 2022, the marriage, his fourth, ended.

Murdoch was more and more encouraged by his daughter Elisabeth to think about his historic legacy and to consider the ways to free himself from Fox, especially as it once again, following the north star of its massive profits, might be the instrument of reelecting Donald Trump. Fox’s fate was yet unresolved at the time of his death.

Excerpted from The Fall: The End of Fox News and the Murdoch Dynasty, by Michael Wolff (Henry Holt and Co.; September 26, 2023).

Michael Wolff will be interviewed by Janice Min on Oct. 16 at Zibby’s Bookshop in Santa Monica as part of our new In Conversation event series. Please RSVP to events@theankler.com. Priority access will be given to paid subscribers.