Marilyn Monroe’s Overdose and the Echo in Matthew Perry

The lurid media circus around the first public drug-induced end

Ed note: Welcome to the debut of Ankler Rewind, dedicated to exploring the vast history of an industry, from true crime to forgotten cultural moments. We’re delighted to introduce Joe Pompeo as our regular columnist (though other voices may contribute). You may know Joe from his stellar work on the media beat the last 15 years, most recently at Vanity Fair, or from his acclaimed book, Blood and Ink: The Scandalous Jazz Age Double Murder That Hooked America on True Crime. You can also follow his own Substack, A Little History. Ankler Rewind appears every other Saturday and, for now, is available to all subscribers.

Hello! And thanks for joining me for my first time at the Ankler rodeo. (Not counting the time I profiled this publication.) Old Hollywood lore fascinates me. I’m a sucker for film noir and Hollywood Babylon and the Black Dahlia. I own books about Confidential magazine and Walter Winchell. What’s not to love?

My hope is that Ankler Rewind feeds your hunger for Hollywood nostalgia through a contemporary lens. My goal is to occasionally shed light on today’s Hollywood culture through the past (though some tales will be just plain spicy and fun). I’d love your feedback as well as any ideas for stories you think are ripe for retelling. You can reach me at joepompeo@substack.com.

While our attention is stretched thinner these days, and our sources of celebrity news and gossip evolved (and devolved), our fascination with stars remains intact. Take the Matthew Perry tragedy. Recently I read a sharp piece about the case by Dan Adler, in which he flicked at “the noirish spirit of the underworld that came into view in court papers and tabloids,” including the “ketamine queen,” allegedly one of Perry’s top drug suppliers. The increasingly grim headlines surrounding Perry’s death heartbreakingly echo what was arguably the most infamous celebrity overdose in Hollywood history: Marilyn Monroe.

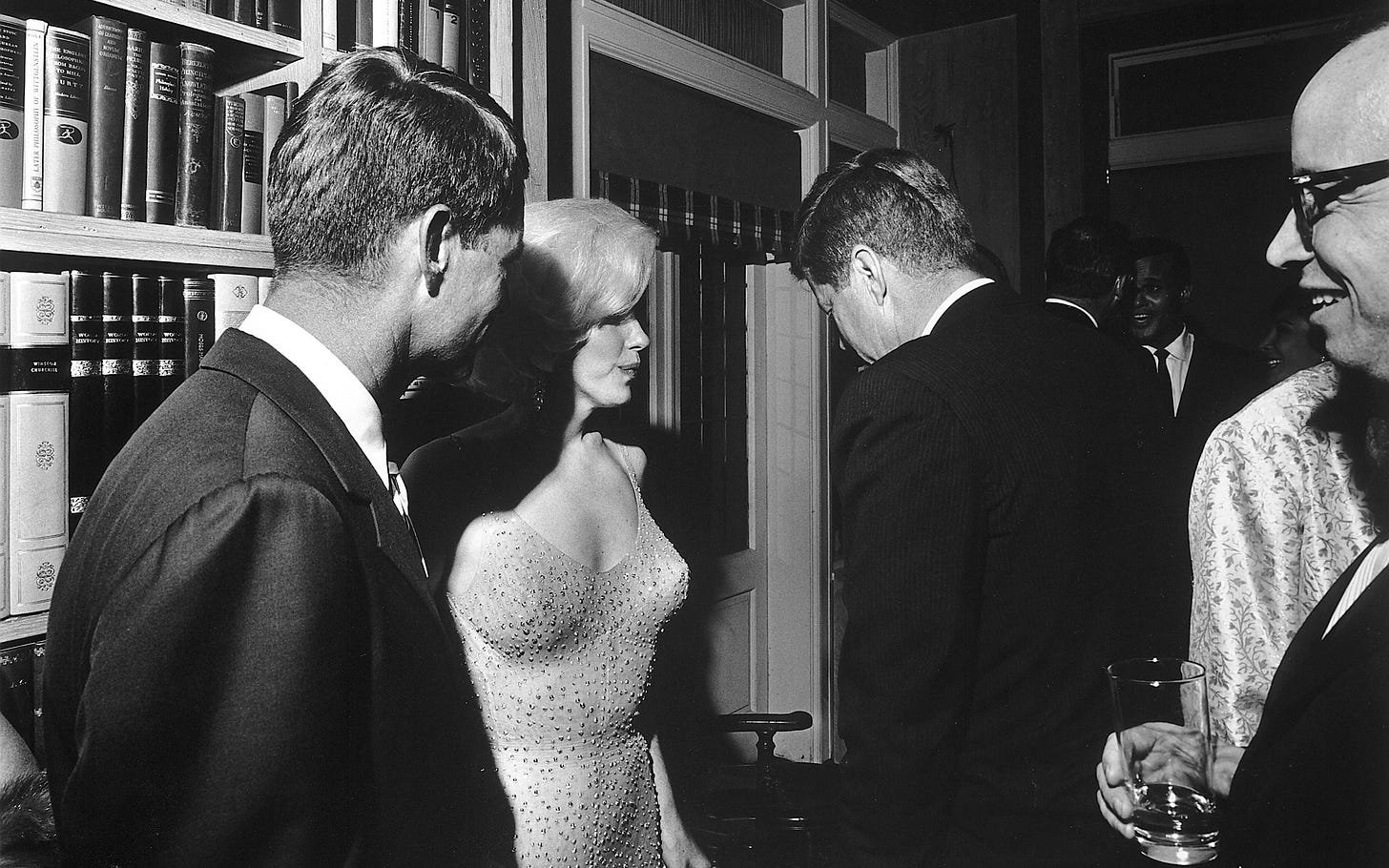

There’s a palpable connection between their narratives, a shared darkness that lurks beneath Hollywood’s glittery exterior. In Perry’s case, it’s L.A.’s network of shady doctors, dealers and high-end rehabs, always just a text message away for troubled stars. With Marilyn, well, you don’t need me to tell you about her alleged mob connections or FBI surveillance or risky romantic entanglements with the Kennedys. (It’s notable, if not surprising, that some of the first-responding journalists at the scene of her death later built successful careers as Hollywood spinners — a flack and a writer.) Both had talked openly about the emptiness of fame, with Monroe, who grew up a foster child, saying in an interview published two days before her death (more of that below), “Fame to me certainly is only a temporary and a partial happiness.”

During those frantic first few days after her fatal overdose — at the age of 36 from acute barbiturate poisoning — America absorbed Marilyn’s sudden death through a torrent of sensational press coverage: the tragedy, the timeline, the toxicology, the mourning, the judgment, the endless search for answers. It’s a template that resonates today: Perry wasn’t the same kind of cultural icon, and his drug problems were already well-known, yet his death managed to stop the presses. Here we are almost 12 months later and it’s still in the air.

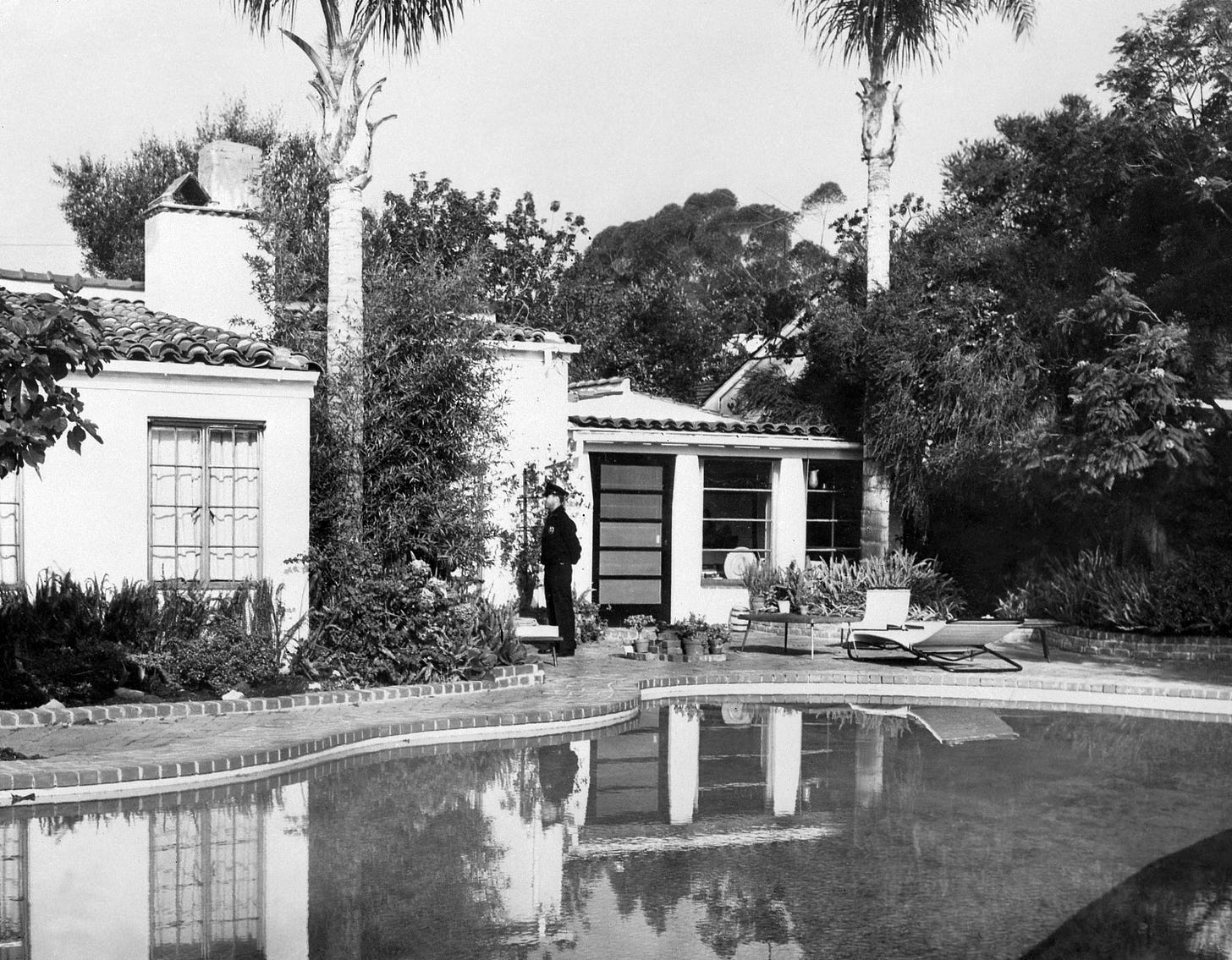

More than 60 years since Monroe’s death, the intrigue surrounding it continues to capture our imagination. To understand how such fascinations endure, it helps to understand how they began. In this case, it was on the morning of Sunday, Aug. 5, 1962, as the sun rose over a Spanish-style four-bedroom in Brentwood that was about to become the world’s most newsworthy hacienda . . .

'I Was Never Used to Being Happy'

By the time Joe Hyams rolled up to the property in his black Mercedes — a hot ride once owned by Humphrey Bogart — his scoop was already a goner. Early that morning, around 5 a.m., an editor at the small news agency City News Service had gotten the tip of a lifetime, from a source in the Los Angeles coroner’s office. While Hyams and other reporters raced to Marilyn’s swanky pad, the editor, Joe Ramirez, raced over to his office to get the story out on the wire.

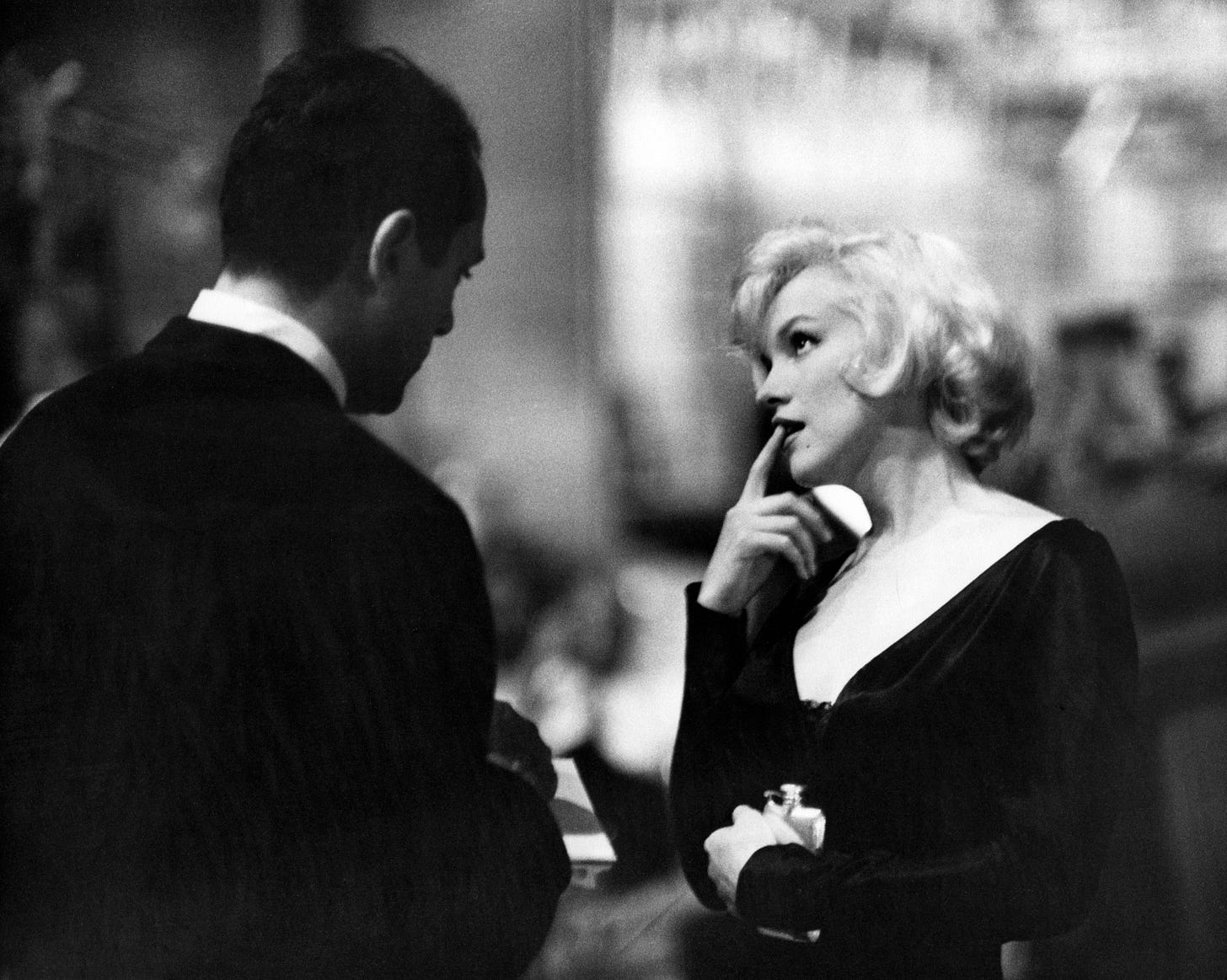

Hyams arrived at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive with his photographer pal Bill Woodfield, who’d been roused out of bed by Hyams at the crack of dawn. The two were no strangers to the actress who lay dead on a mattress inside her single-story home, the only one she’d ever bought for herself. Hyams, a New York Herald Tribune correspondent who would go on to become a legendary publicist for Warner Bros., had interviewed Marilyn on more than one occasion, including on the set of her final musical performance, 1960’s Let’s Make Love.

Woodfield, who would later find success as a screenwriter and producer (scoring Emmy and WGA award nominations for his work on Mission: Impossible), was one of several photographers who’d recently captured naked images of Marilyn in a swimming pool on the set of Something’s Got to Give, a screwball comedy that would never make it to screens.

In a matter of days, Hyams and Woodfield would find themselves chasing a wild lead: that Bobby Kennedy had been rushed by helicopter to LAX hours before Marilyn’s death. For now, though, they were focused on the who, what, when and where. They’d get to the why soon enough.

The pair were joined by other journalists, including James Bacon, an Associated Press columnist who’d remained friends with Marilyn after a fleeting dalliance. He strode past a cluster of pajama-clad gawking neighbors and approached one of the officers standing guard. Lying through his teeth, Bacon said he was from the coroner’s office, and the cop gullibly waved him into the house.

Marilyn had closed on the place just six months earlier for a reported $75,000 (about $782,000 today). Earlier this year, a public outcry saved the house from destruction, cementing its designation as a cultural landmark after a public battle that highlighted the romance and reverence her legend still commands.

“I didn’t stay long, just long enough to see her lying there on the bed,” Bacon later recalled. “I noticed that her fingernails were unkempt.”

The assembled newshounds could tell that the police were treating this as an unnatural death. They watched detectives cover Marilyn’s bedroom with what Hyams described as “large, canvas, evidence-preserving cloth.” Around 7:30 a.m., an actual member of the coroner’s office emerged from the house. Moments later, cameras snapped away as EMTs wheeled out Marilyn’s body and loaded it into a battered 1950 Ford station wagon bound for the Westwood Village Mortuary.

It wasn’t long before photographers weaseled their way into the morgue. One of them was the renowned lensman Leigh Wiener, on assignment for Life magazine. After bribing an attendant with a bottle of whiskey, he shot five lurid rolls of film, including a chilling photo of Marilyn’s left foot poking out of a refrigeration unit, an I.D. tag dangling from her toes.

Life, as it happened, had published an interview with Marilyn just two days earlier in its Aug. 3 edition. Her quotes, in retrospect, were foreboding:

“I was never used to being happy, so that wasn’t something I ever took for granted.”

“Fame to me certainly is only a temporary and a partial happiness.”

“I think that when you are famous every weakness is exaggerated. This industry should behave like a mother whose child has just run out in front of a car.”

In the most haunting soundbite of the bunch, Marilyn had remarked of her career: “It might be kind of a relief to be finished. It’s sort of like, I don’t know what kind of a yard dash you’re running, but then you’re at the finish line and you sort of sigh — you’ve made it! But you never have — you have to start all over again.”

Perry similarly reflected in his memoir, Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, published one year before his death, “You have to get famous to know that it’s not the answer. And nobody who is not famous will ever truly believe that . . . I think you actually have to have all of your dreams come true to realize they are the wrong dreams.”

'There Was No Dignity in Her Death'

Hyams left Marilyn’s house and sat down to write his latest Hollywood dispatch for the Herald Tribune. The following morning, it would be syndicated in newspapers all over the country. “Marilyn Monroe, the troubled queen of filmdom,” he typed, “was found dead of an overdose of sleeping pills at her home here early Saturday morning. She was 36, childless, [and] obviously wretched about her fading career.”

Hyams described the discovery of Marilyn’s body as his sources had described it to him: At 2:55 a.m., Marilyn’s housekeeper, Eunice Murray, had awoken suddenly “with the ominous feeling that something was not right.” Murray knocked gently on Marilyn’s door. No answer. Alarmed, she darted out the front of the house and around to the side. Peering through the drapes of a large locked window that opened onto Marilyn’s bedroom, Murray’s heart raced as she laid eyes on her employer, face down on a king size bed beneath a champagne-colored blanket.

“She looked like a still life portrait of a little girl,” Hyams wrote, “who had fallen asleep while talking on the telephone — the receiver was still in her hand.”

Murray ran back into the living room and phoned Marilyn’s psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, who arrived within minutes from his nearby home. At 3:10 a.m., Greenson banged on the bedroom door, ramming into it with his shoulder. “MARILYN!” Still no answer. The door wouldn’t budge. Greenson grabbed a tool from the fireplace, rushed over to the side window, smashed one of the panes, undid the lock, and climbed through. Inside, he found his patient’s lifeless, naked body next to a nightstand strewn with pill containers, and an empty bottle of Nembutal on the floor.

“My last glimpse of Marilyn Monroe,” Hyams lamented, “was as they wheeled her into the mortuary side entrance, into a storeroom, littered with coats, drafting tables and dust brushes. The door was then locked. The girl who struggled all her life trying to find dignity as a human being was being left alone in the dark in a shed.” As with the discovery decades later of Perry’s body simmering in a hot tub, “There was no dignity in her death.”

Marilyn’s overdose ricocheted around the globe on radio, television and the front pages of major newspapers. The Los Angeles Times ran one of those screaming eight-column headlines reserved for monumental news events. Condolences for Marilyn rolled off the tongues of shaken stars, from Dean Martin to Gene Kelly to Jayne Mansfield. Peter Lawford, the Rat Pack fixture — and husband of Patricia Kennedy — who would become a key figure in the coming probes into Marilyn’s Kennedy ties, said, “Pat and myself loved her dearly. She was a marvelous, warm human being.”

A particularly lyrical encomium found its way to readers on the other side of the Atlantic, where The Guardian observed:

Marilyn Monroe was found dead in bed this morning in her home in Hollywood . . . She dies with a row of medicines and an empty bottle of barbiturates at her elbow. These stony sentences, which read like the epitaph of a Raymond Chandler victim, will confirm for too many millions of movie fans the usual melodrama of a humble girl, cursed by physical beauty, to be dazed and doomed by the fame that was too much for her.

'A Myth of What a Poor Girl Could Attain'

Over the next few days, the media sunk its teeth deeper into the story. “Marilyn Monroe’s second husband, Joe DiMaggio,” the New York Daily News reported, “today stepped into the confusion created by the star’s death and a few hours later funeral arrangements were announced.”

A despondent DiMaggio, at the suggestion of Marilyn’s half-sister, had agreed to take charge of the arrangements. She was to be buried Wednesday in a small cemetery beside the Westwood morgue, “only a few minutes walk from the first home she ever owned — where she died Sunday,” as Hyams noted, “and only a few miles from the 11 foster homes in which she grew up as a child in poverty.”

A toxicology report concluded that Marilyn had consumed nearly twice as much barbiturate as was needed to stop the beating of her heart. But there were juicier headlines to be had.

Eunice Murray, the housekeeper, dished to reporters that Marilyn had struggled with depression and insomnia, and that she’d spoken with Greenson, her psychiatrist, for about an hour earlier in the day. Some newspaper reports zeroed in on a “mysterious phone call” that Marilyn had received, according to Murray, after retiring to her bedroom on Saturday night.

“I don’t remember what time the call came in, and I don’t know who it was from, but knowing Marilyn as I do, I think that if this call waked [sic] her up she might have taken more sleeping pills,” Murray said. “She seemed disturbed after the phone call. When she went to her bedroom, she really was depressed because she couldn’t go to sleep.”

Who was the mystery caller? Speculation surfaced that it might’ve been José Bolaños — a leftist Mexican filmmaker described as “Marilyn’s frequent escort in her last months of life” — after it was learned that detectives sought to question him. (Bolaños may also have been at least partly to blame for Marilyn being on the FBI’s communist radar.) A newspaper in Mexico City published an article suggesting Marilyn had taken her life due to an unrequited love for the 35-year-old. Marilyn’s representatives emphatically disputed the claim, but it made for salacious gossip.

Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Times ran a front-page story about someone who definitely had phoned the Brentwood abode on that fateful night.

Joe DiMaggio, Jr. had reached out to his one-time stepmother, with whom he remained friendly, around 8:30 in the evening. (Girl troubles.) This meant that the 21-year-old Marine was the last known person to speak with Marilyn before she died. On Tuesday night, he arrived by bus in Santa Monica, where he joined his father at the Miramar Hotel and “declined to discuss Miss Monroe other than to say he was deeply shocked.”

The following afternoon, Wednesday, Aug. 8, at the Westwood Village Mortuary Chapel, DiMaggio leaned over his ex-wife’s bronze casket, kissed her lips, and whispered, “I love you, I love you.”

The erstwhile Yankees star had insisted on an intimate ceremony; no press and a modest guest list consisting of two to three dozen family members, close friends and confidantes. Marilyn’s celebrity associates, the Frank Sinatras of the world, were conspicuously uninvited. If it hadn’t been for some of them, DiMaggio was said to have snapped, “she wouldn’t be where she is.” Patricia Kennedy Lawford had flown in all the way from Hyannis Port, only to learn that she would be refused entry.

The scene outside the chapel was less subdued. Fans and journalists were kept at bay by city police, security officers and even Pinkerton guards. Among the reporters clustered in the blistering sun was Walter Winchell, the legendary gossip columnist and inveterate celebrity scourge who’d carried DiMaggio’s water during the divorce. The doors to the chapel opened, and funeral attendees began filing across the lawn. Winchell, perhaps hoping to land an exclusive ride-along to Marilyn’s crypt, cried out, “Joe! Joe! It’s Walter Winchell.” But DiMaggio just kept on walking.

The eulogy was delivered by Lee Strasberg, Marilyn’s friend and acting coach. “In her own lifetime, she created a myth of what a poor girl from a deprived background could attain,” he said. “But I have no words to describe the myth and the legend. I did not know this Marilyn Monroe. We, gathered here today, knew only Marilyn — a warm human being, impulsive and shy, sensitive and in fear of rejection, yet avid for life and reaching out for fulfillment . . . In our memories of her she remains alive.”

Hyams, back at his desk after the funeral, transcribed those sentences for the following morning’s Herald Tribune. As he typed out this latest entry in the saga that had consumed his past four days — and would consume more to come — he thought about the clamor of Marilyn’s life in contrast with the softness of her sendoff.

“Marilyn Monroe, the unwanted, friendless child who became the most famous glamor symbol of her time, was entombed yesterday with the quietest, most modest funeral ever given Hollywood royalty,” Hyams wrote. “It was almost as though Marilyn Monroe had never been a movie star. There were no celebrities at her funeral, only the kind of folk one expects at [a] funeral to say goodbye to more ordinary people . . . Marilyn Monroe had come full cycle: From a simple and tragic childhood to a simple and tragic ending of her life.”

Hyams filed his story and got back to reporting. The mystery had only just begun.

Tragedy, Truth and Justice

In the aftermath of Marilyn’s death and in the years to come, reporting from Hyams, Woodfield and, most assiduously, Anthony Summers (author of the 1985 biography Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe), would poke holes in the official timeline of Marilyn’s death, eventually forming the basis of a 2022 Netflix documentary. Norman Mailer would amplify the claim that Marilyn was murdered over her alleged affair with Bobby Kennedy. Titillating theories and conspiracy-mongering would spread like weeds, raising more questions than answers.

“Why was there no glass of water by her bed at the crime scene if she swallowed a lethal number of pills?” one unabashed believer wondered aloud in CrimeReads last year. “Why did it take an hour or more before the LAPD was called after she was found dead? . . . And why did the beachfront neighbors of Robert Kennedy’s brother-in-law report that sand got in their pools because a helicopter landed and helped Kennedy escape his lover’s crime scene?”

We’ll never know the whole truth, and those still seeking justice for Marilyn will surely never attain it.

Perry’s justice, on the other hand, has been playing out in the press just as feverishly as his demise: “San Diego doctor agrees to plead guilty in death of Matthew Perry, surrender license”; “Trial Date Set for Pair Charged in Matthew Perry’s Death”; “The Case Against Matthew Perry’s Accused Killers.”

These two kindred sagas remind us that, now as then, fame can be cruel.

A note on sources:

In reconstructing these scenes I drew on an array of historical articles from The Los Angeles Times, The New York Herald Tribune News Service, the New York Daily News, The Los Angeles Evening Citizen-News, United Press International, the Associated Press, and the Long Beach Press Telegram. Portions of Anthony Summers’ Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe, were indispensable, and the Netflix documentary based on Summers’ reporting informed my understanding of the questions surrounding her death. Vanity Fair, Life, The New York Times, The Hollywood Reporter, Variety, Deadline, the Daily Mail, The Guardian, El Pais, and Getty Images also came in handy.

An interesting side note regarding the Walter Winchell anecdote: There are a few obscure references online to Winchell being the only reporter allowed to attend Marilyn’s funeral, supposedly because of a friendship with Joe DiMaggio. The legendary AP Hollywood correspondent Bob Thomas recalled the opposite in his remembrances of the funeral published in 1971 and 1998. I went with Thomas’ version.

Hi Joe, I love your debut piece on Marilyn. I'm a longtime Ankler reader, listener, and fan. You guys also acknowledged my pr work with disabled talent with an Ankler hat! As a Rat Pack devotee, I absorb everything Marilyn. Your article caught my deep Rat Pack interest. One of my highlights was having Joey Bishop phone chat buddy for five years before his death. He used to enthrall me with stories about his friendship and collegiality with Marilyn and friends. Looking forward to more Hollywood "Rewinding." Vince Staskel

"Hollywood Babylon" is complete bullshit from page one to page last. Particularly the "account" of the Fatty Arbuckle "murder," which has no connection whatsoever with the truth (I wrote an award-winning documentary on the true facts in that case). If this is the kind of stuff you're going to recycle, I'm regretting my subscription five minutes after I made it.