Exec Jon Glickman: 'We're Entering a Radical Transition Period'

Now at Miramax, the longtime leader on his optimism and why AI can be a force for positive change: 'There's an opportunity for new voices'

All week, I've been having conversations with some of the smartest people I know in this industry to talk about the state of the business, including Sarah Schechter, R.J. Cutler, Lorenzo di Bonaventura and Colin Callender. These are people who have accomplished big things in their time and continue doing so, and who have, notably, built careers with longevity, and more importantly, have the ability to share their thoughts uncensored today.

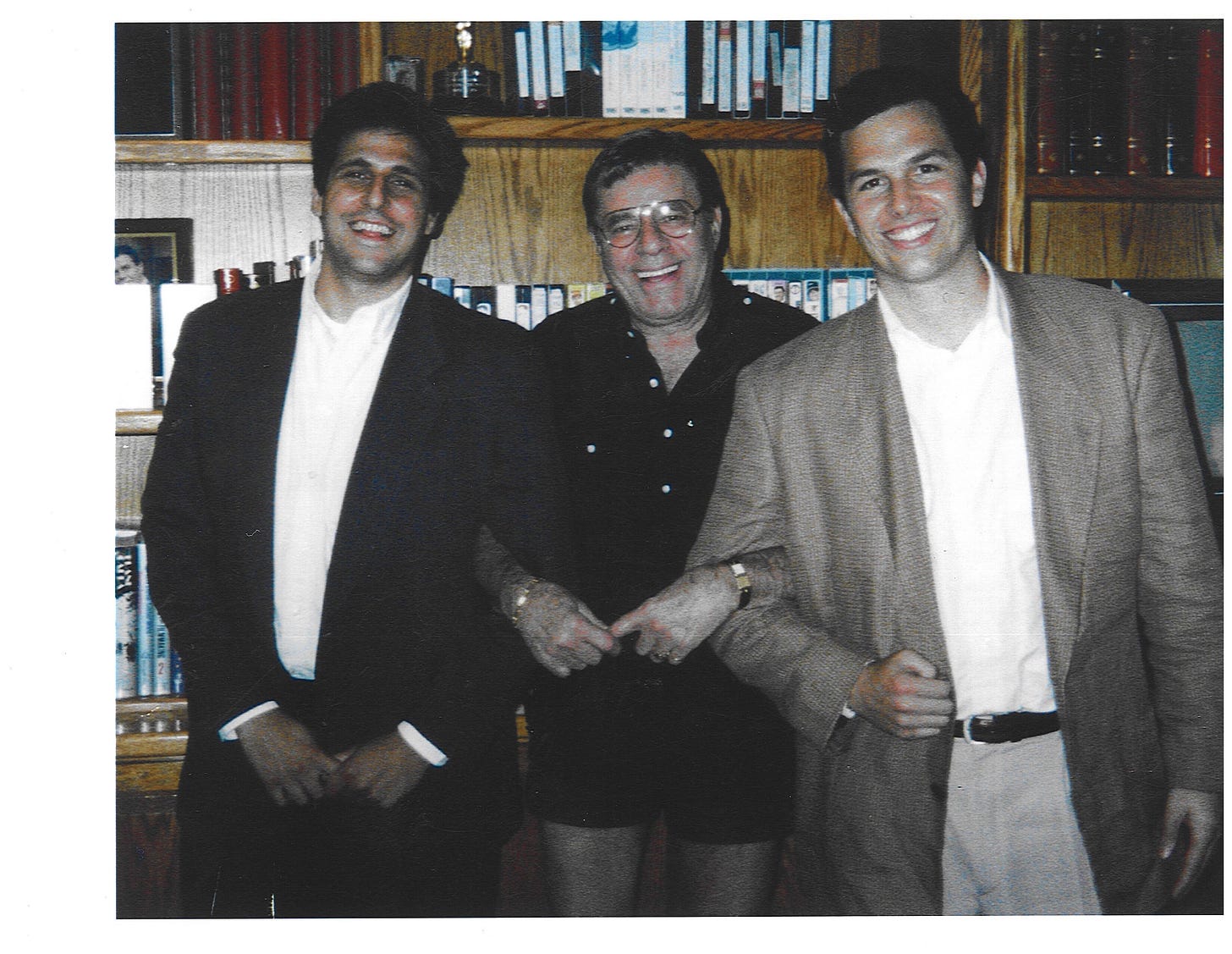

My fifth and final maven is Jon Glickman, the CEO of Miramax and former president of the MGM Motion Picture Group. Born in Detroit and raised in Kansas and Washington, D.C., Glickman has the entertainment industry in his blood. His father, Dan Glickman, was the former Secretary of Agriculture under President Bill Clinton and later succeeded Jack Valenti as head of the Motion Picture Association of America. In the ‘90s, Glickman got his start at Caravan Pictures under Joe Roth (his first project was The Jerky Boys: The Movie). By 2002, he became president of production at Spyglass Entertainment. Among the movies Glickman has produced are Rush Hour and its sequels, Shanghai Noon and Shanghai Knights and 27 Dresses.

In 2011, Glickman took over the film division at MGM, where he helped relaunch the Rocky franchise with Creed and shepherded the James Bond hits Skyfall, No Time to Die and SPECTRE. After leaving MGM in early 2020, Glickman set up Panoramic Media, where he executive produced the Netflix hit Wednesday. In 2024, he was named CEO of Miramax, where he remains today.

So, not a bad resume for someone to talk about the state of Hollywood. In our conversation, Glickman explains why AI might lead to some positive outcomes for the industry, how “the stranglehold that the streamers had… owning rights and not giving downstream economics to producers has been a disservice,” how “IP-focused global extravaganzas” have turned executives into brand managers, why we should look at 2019 as a surprisingly creative year, and why improving incentives for producers will improve the industry overall:

“If you’re making a film or a television show that you’re going to participate in the success of for the rest of your life, you will do whatever you can to make sure that the long time value of that product, your film, TV show that you’re working on, is going to be successful.”

Many more smart thoughts, and definitely not just doom and gloom below. Enjoy!

Richard Rushfield: So how do you think it’s going for Hollywood?

Jon Glickman: I’ve done this for almost three decades now, and I think we’re in a seismic change that the business has been going through. So I don’t think the question is, ‘Is it good or bad?’ I think it’s that we’re now going through a period of transition, similar to talkies, color television, home entertainment. It’s something that I certainly haven’t experienced in my entire career. We had 25 to 30 years of calm, and with streaming, and now, with AI, we’re entering a radical transition period. However, historically, Hollywood has adapted and navigated through these transitions, and power has become more democratized, allowing the industry to become even stronger when these issues are resolved. So, I have confidence that will be the case once we work through the next few years of figuring it out.

What are some possible good outcomes you see?

Well, it’s interesting. Obviously, with AI, there are a lot of issues to navigate. We’re a library company at Miramax, and first and foremost, we have to protect our IP. It’s very unclear how these AI companies are mining that IP, and you have seen the lawsuits as a result. I think that we certainly learned from your business (journalism) that you’d better fight this at the beginning, rather than hope that you’re going to be able to survive, because look what happened to journalism.

How does this end up as a positive force?

There’s an opportunity here for new voices by using the tools of AI to establish themselves as filmmakers and storytellers in a system that, over the last few years, has been difficult to crack. The gatekeepers have grown older and more static in their ability to allow new voices to speak up. I liken it to what happened in the music business with garage bands, where you didn’t have to go into a recording studio to make a demo anymore. You could do it in your bedroom. People who wouldn’t necessarily have gotten chances, like Billie Eilish and her brother, and a lot of the hip-hop artists, became famous on SoundCloud. But it will happen that you start seeing stuff and think, ‘Wait a second, that looks incredible!’ And that kid wouldn’t have had the tools with which to say, ‘Here’s a new character that I created,’ or ‘Here's a new story that I created.’ And now they can do it alone.

How do you see the industry responding to that?

Well, my biggest hope is that we’re going to unify the business by this process, and that people are now going to be able to come in and show their talents outside of the system, and then hopefully work their way into the system. That’s a very positive outcome compared to where we’re at right now. Certainly, there are positive elements in the streaming world. Consumer choice is always a good thing. But we’re getting to a place where there has been so much content, it’s hard for anything to sort of have a cultural impact.

So you don’t feel like we're seeing an unravelling of the industry?

It might seem dire at this instant. But the birth of VHS was called ‘the Boston Strangler’ by Jack Valenti, the head of the MPAA. Lew Wasserman sued to stop people from being able to record stuff in their houses, and it ultimately became a huge revenue center. Many up-and-coming filmmakers were able to enter the business because of home entertainment. So, I think we’ll get through it, and we just need smart people to navigate us through it, to cooperate between the studios, labor and consumers. We all need to work together.

In your career, you’ve worked in the studio orbit, but not directly for the major studios. Do you think that taught you an agility that serves you well at this moment?

I’ve been lucky enough that when I started in the business, there was such a demand for feature film content. I started as a film producer, even though I moved into the television world. It just was a different time, because the studios were looking to increase their libraries, in terms of IP, and there were so many revenue streams downstream. That’s where the home video revolution really took off. And again, this was something that was considered to be the end of the film business on some level. But what it ultimately did was allow you to make movies and then figure out, ‘Okay, we’ll sell them after they’re in theaters for a certain window. We’ll go and sell them directly on VHS or sell them directly on DVD. Then you’ll have pay TV windows, and then you’ll have free TV windows, and then you have all those international sales.’ And it was very difficult not to make money on movies at that time, because there were so many revenue streams. I was lucky that I got a lot of experience at that moment in the business where there was a huge opportunity downstream, and it just felt like there was less pressure on the initial theatrical window.

So were there more opportunities to try different things?

In getting to make movies inside that system, there was a lot more ease to it, and you could take shots. In the old days, studios would make 18-plus movies, and because the downstream revenue was so consistent, you could take risks on movies. I was lucky that I got a lot of experience, and I made a lot of movies in that world.

What happened to a business that felt so young, and now seems very calcified?

I think there are several reasons why it has gotten older. Some of it is lifespan. I think people are living longer, so people are hanging on to jobs. I saw this incredible documentary about Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss, and they were forced into retirement. These are two of the most prominent music executives of all time, who were forced into retirement at the age of 60. That would never happen today.

They would be the youngest execs in the business.

Exactly, the upstarts. So I think that’s a big factor in it. But something happened around the time of Marvel and the live-action remakes of films at Disney. These IP-focused global extravaganzas made the film executive job and the producer job, on some level, much more of a brand manager than a producer of individual titles that could succeed on their own.

When did you notice the change?

I remember I had a conversation with a friend at Disney, and they just had a big romantic comedy hit that made $35 million or whatever. He came back and he said, ‘That’s meaningless for this company now, a movie like that just doesn’t move the dial.’ Whereas that was the lifeblood of the business that I grew up in. But that openness before allowed more inexperience and more people to break in. The first movie that I produced was a movie based on two prank phone callers who never acted a day in their lives, and I was allowed to go produce the movie. I had never produced a movie in my life. But because it was a limited risk, and because you knew you were protected downstream, I got the opportunity. I had a mentor in Joe Roth, who said, ‘Go off and do it.’ I was able to learn because of the quantity of movies, and that the stakes weren’t life or death.

What did you learn on producing that first movie?

I was so inexperienced. I directed a student film at USC that starred an actor named PJ Clapp, now better known as Johnny Knoxville, and was edited by one of my frequent creative collaborators, Miles Millar, with whom I later did Shanghai Noon. He is now the co-creator of Wednesday, the TV show. We have a 30-year-plus relationship, but that was my entire experience of making a movie. So I was sort of thrown into a trial by fire. I had bosses — Joe Roth and Roger Birnbaum – who believed in learning by doing. I was obsessed with movies as a kid because I was raised on VHS as part of Generation X. We were able to watch Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid or Fast Times at Ridgemont High over and over again at our choosing. That instinctively gave me a feel for movies. I had one year of experience at USC grad school that I dropped out of to work for Joe Roth. I probably made a monstrous amount of mistakes on that movie, but it gave me the real-world experience to do it.

How did you move forward from there?

The second movie I produced was the script I found. Because again, there were so many movies being made at that time, and there was a real spec market. People looking for original IP, and you’d read three scripts a night. I was low enough on the totem pole at Joe Roth’s company to read an original script called Coma Guy, about a girl who falls in love with a guy who falls into a coma. And I liked it, and I told my boss I wanted to do it. And Joe was like, ‘Great, let’s go do it.’ I’m not even sure he read it, and we bought it. And when we were casting that movie, which turned into While You Were Sleeping, we were able to put in an actress who wasn’t a superstar yet, Sandy Bullock, because at that time, people wanted freshness and people wanted originality in the theater. If the movie didn’t work, nobody was going to get killed. That was a different sensibility than what we have today. However, it created numerous opportunities for me to learn on the job and trust my instincts as a young person. To say that this person, who is incredibly fun in Speed, should be the star of this movie, not an established star.

What is the sensibility we have today?

It’s more of a top-down system where the heads of the studio are saying, ‘Okay, we need to make this type of movie or exploit this brand, and who is the executive that is going to manage that brand for us?’ And that’s almost how you get rewarded. ‘I’m going to be the executive on the James Bond movie. I’m going to be the executive on the new Avengers movie, or the new Fast and the Furious.’ The biggest difference now is that there’s not really a system for people to fight for something. It happens, but it’s not what the system is reliant on, which is what it was in the old days.

Is this just a doom loop where new ideas and new talent are locked out?

It reminds me of our political system on some level. We’ve allowed this thing to age and harden. But streaming and the potential positives of AI can crack that wide open, and we can now bring in new voices.

What’s the Mark Twain line? History doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes. An executive showed me the story that was written in the New York Times about how studios were stuck in remakes and sequels, and developing TV shows. That article was written in 1966 by Peter Bart. It was a year before Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, all of those movies, the Easy Rider revolution. But these conversations we’re having now are feeling similar to the conversations that were happening right before the entire system blew out.

Are new voices entering the system? Is that something that studios are going to do, or are they going to find their way up on the outside and storm the gates eventually?

Almost always, it happens outside the system, and then the studios bring them in.