When JFK Jr. and David Pecker Made a Magazine, and Went to Mar-a-Lago

Over email, the disgraced publisher recounts the years the scion was Pecker's ticket to the big time — and his calling card to Donald Trump

In the mid-nineties, magazine publishers stood astride the media landscape. Print advertising pages were almost as voluminous as the black town cars idling outside the media titans’ midtown New York City skyscrapers to ferry employees wherever they needed to go. A new idea with the potential to be a hit could translate into eight or even nine figures in annual profit, and publishers were hungry for additional titles to keep everyone in expense-account lunches at Judson Grill for perpetuity.

At that moment, one might be startled to see John Kennedy Jr. standing astride his bike waiting for the light to change on Sixth Avenue, as he pedaled from one midtown publisher to another trying to peddle his idea for a new magazine. JFK Jr., 34, and the only son of the 35th president, had been a celebrity since before he was even born. Now he had a vision for a magazine that would blend left- and right-wing politics with pop culture.

Kennedy’s pitch fell on deaf ears at both Hearst and Conde Nast. Hearst particularly did not want to be in the political space, and Conde’s Vanity Fair was already doing some of what Kennedy was suggesting. Even Jann Wenner, owner of Rolling Stone, believed that politics just wouldn’t sell. Back then, political magazines — such as The New Republic and National Review — were high-minded policy journals for small Beltway audiences and not glossy, mass-market banners.

Then JFK Jr. found his way to 1633 Broadway, just off 51st Street, the headquarters of Hachette Filipacchi. The French-owned publisher of Elle and Metropolitan Home may have seemed like an odd fit for what Kennedy had in mind, but for one thing: CEO David Pecker.

Martha Stewart’s lifestyle magazine, Martha Stewart Living, had just increased its frequency to a monthly magazine. Kennedy was one of the most famous people in the world, from the closest thing America had to a royal family. His name may not have been in the title of his proposed magazine — dubbed George, for the first U.S. president — but everyone would know it was his. For the person who made that dream happen, Pecker, it could elevate his station not only in the New York media scene but in society.

He agreed to put more than $20 million (more than $40 million today) into George and moved Kennedy’s burgeoning team into the company’s midtown offices.

“[Pecker] graduated from Pace and wasn't like any of these white shoe, elitist kind of guys,” says Keith Kelly, the former magazine beat reporter at the New York Post. “He was always kind of an outsider. And I think he embraced John [Kennedy], because he figured out a way to get in with that crowd.”

Almost 30 years later, as Pecker testified in Donald Trump’s hush-money trial in a New York courtroom far from the once glittering epicenter of print media, one could not help but think that Pecker getting into business with Kennedy represented a signal moment in his path to the witness stand at the tawdry trial of the former president.

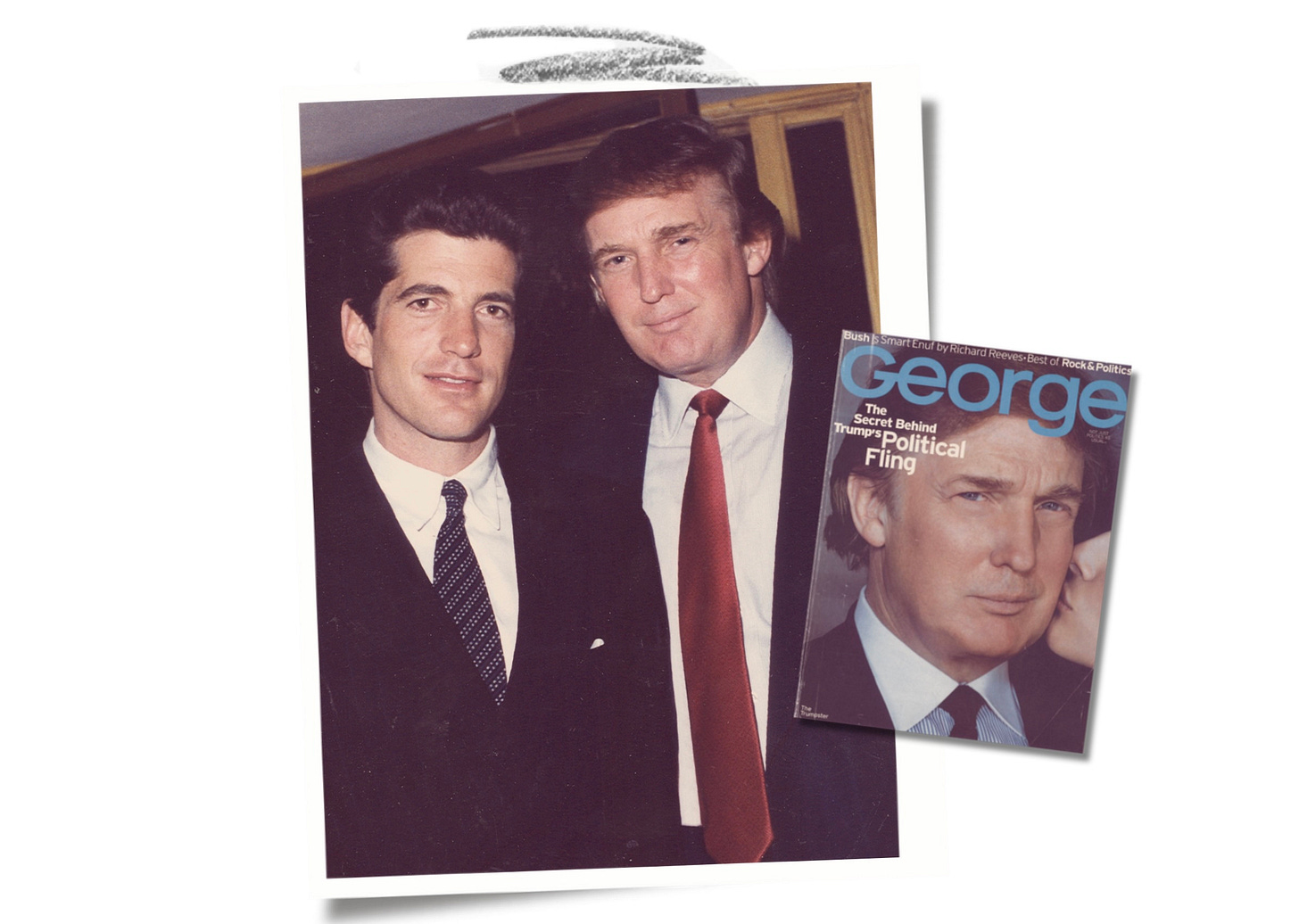

JFK Jr. and George gave Pecker an entrée into elite circles. Soon after, that would include Trump, who would eventually make it on to George’s cover. If George had fulfilled its early promise, perhaps Pecker would have had a different trajectory in the media world, one that may have made him less famous — but also less infamous.

And like so many of David Pecker’s relationships, this one too ended badly.

Yet Pecker, still, wants to correct the record, as he does in emailed statements below.

George and the Media Jungle

Kennedy, creative director Matt Berman and the rest of the editorial staff got to work bringing JFK Jr.’s vision to life. The timing felt ripe in 1995 for a political lifestyle magazine. Rep. Newt Gingrich had just pulled off the Republican Revolution, putting the GOP in charge of the House of Representatives for the first time in 40 years, and President Bill Clinton was triangulating to try to maintain power. Fox News and MSNBC, the 24-hour cable news networks that would grow to become political entertainment lifestyle brands in their own right, were fledgling enterprises.

They conceptualized expensive cover shoots with Cindy Crawford, Barbra Streisand and Robert De Niro, and Kennedy himself would interview a notable figure in each issue, from George Wallace to Warren Beatty to former President Gerald Ford to Charles Barkley. The marriage of politics and pop culture would be joined in such provocative recurring rubrics as one imagining the likes of Madonna and Rush Limbaugh as president.

Meanwhile, Pecker hit the phones to woo his best buddies — Arie Kopelman, then president at Chanel, and Phil Guarascio, the cigar-chomping head of advertising at General Motors — to commit their ad dollars, which they readily did. Pecker also successfully courted the likes of Leonard Lauder, Barney’s Gene Pressman, ad guy Peter Arnell, designer Isaac Mizrahi and the then-president of Maybelline, John Wendt.

In an emailed statement this past week, Pecker described a typical day to me, saying, “I worked from home in the morning and did calls with the French executives in Paris since the timing is 6 hours ahead. I always booked an advertising lunch either at the 21 Club or the 4 Seasons [sic] then I would arrive at the office and stay ‘til 9 p.m.”

Even the possibility of a meeting with Kennedy would get Pecker in the door with the slip-on shoe, silk-handkerchief-in-the-top-pocket ad buyers in Detroit. Women would cancel vacations to be in the same room as Kennedy. Former Hachette staff confirm that Pecker saw Kennedy as a way to elevate himself in society. He would have his assistant call to get Kennedy, whose George offices were on the 41st floor, to come up to join his meetings on the 45th floor.

The association also helped Pecker get the best tables at Le Bernardin, the Four Seasons, and other media haunts like Rao’s, the city’s most exclusive spaghetti joint. Pecker liked to send partners Rao’s products as gifts and, as Keith Kelly recalls, may have even sealed the deal to launch George from the restaurant.

Whatever happened with the magazine, the handsome Kennedy scion would help launch the tall, loud talking, publishing executive with the “heh, heh, heh,” Beavis-and-Butthead laugh into a new social circle — one he desperately wanted to join.

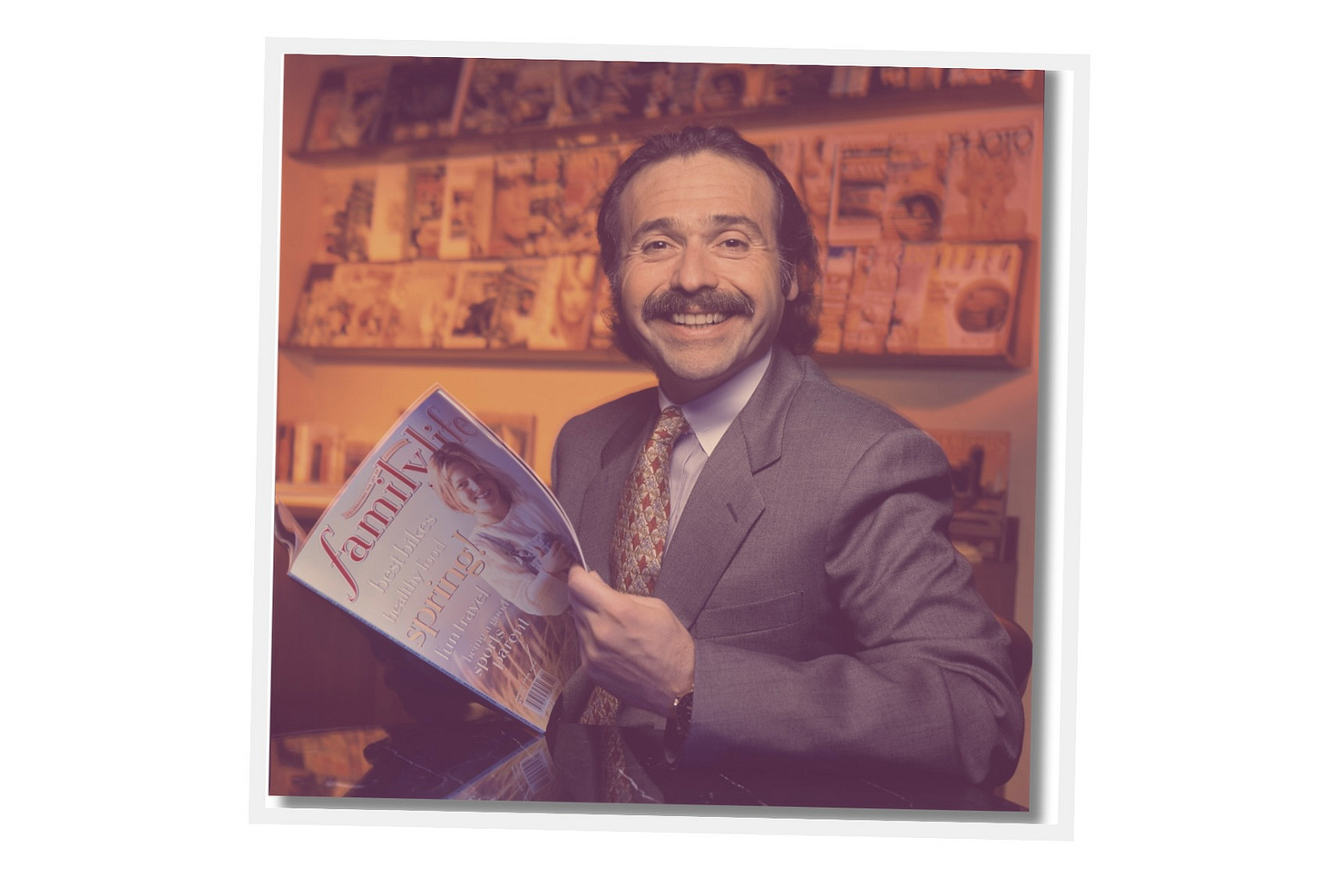

The Climber

Pecker, born in 1951, is the son of a bricklayer from the Bronx. People who know him describe him as down to earth, easy to talk to and a shrewd businessman. He readily took Kennedy’s pitch not only because of who he was but he would speak to almost anyone who had an idea. But Pecker could also be intimidating and quick to cut people down with his quick wry sense of humor, a former executive recalls.

As Kelly says, “If you were a half a step above him on the social scale, he’d kiss your ass. If you were half a step below him, he didn’t want to know your name.”

After doing bookkeeping for local businessmen and studying accounting at Pace University, Pecker was hired at CBS to run the company’s magazine department and then moved up the chain on the finance side. (In the 1980s, the company owned such titles as Woman’s Day, Family Weekly, Car & Driver and Road & Track.)

Hachette Filipacchi absorbed CBS Publications via a $712 million acquisition of Diamandis Communications in 1988 but later declined to sign Peter Diamandis to a new contract. Senior management threatened to exit, and they were surprised when Pecker stealthily maneuvered to seize control.

Pedal to the Meddle

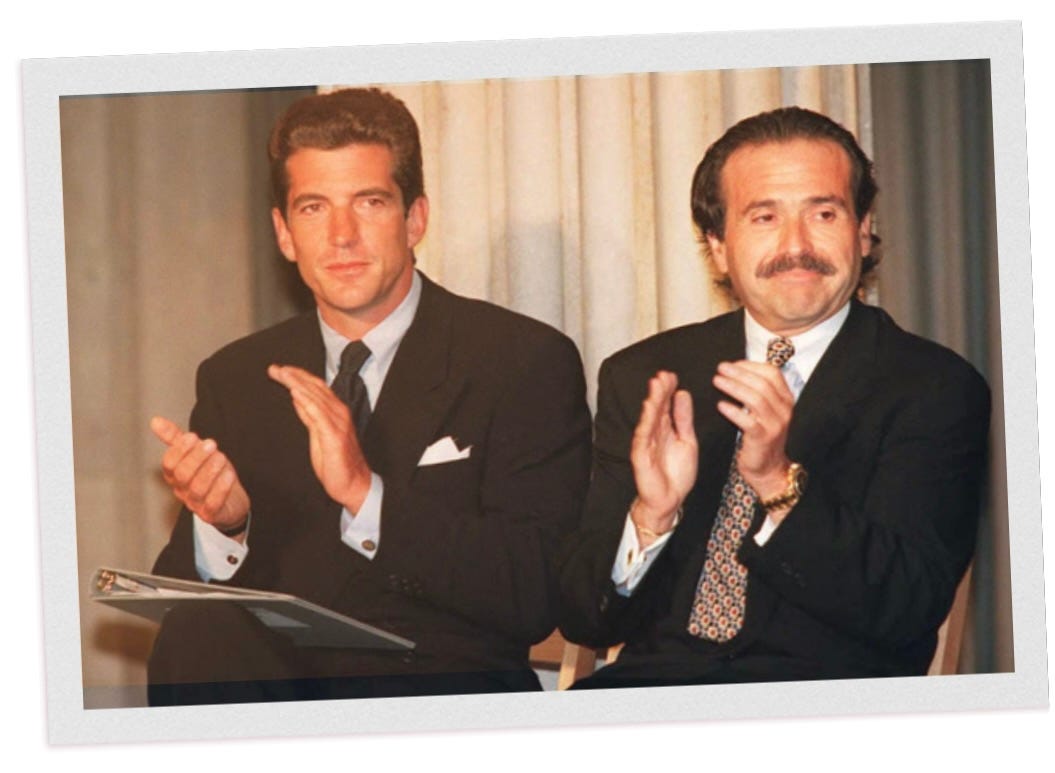

On September 7, 1995, Kennedy, his business partner Michael J. Berman (no relation to the George creative director) and Pecker were at New York’s Federal Hall to unveil the first cover: Crawford dressed as George Washington. Pecker, who had told New York magazine earlier that summer that the magazine was “a living, breathing orgasm,” was on cloud nine that day.

It was not a secret that Pecker pushed to be involved beyond his job description. “David wanted to make a mark, he didn’t just want to be a CEO, operations guy,” says one former colleague. “One of David’s strengths was that he did not — he initially thought he could influence the editorial — but when he realized he couldn’t, he backed off.”

As one person who knew both JFK Jr. and Pecker, tells me, “He allowed John to do his vision, I’ll give him credit for that.”

This may not have applied across the Hachette portfolio. Around this time, Pecker became known among journalists for pushing friends for cover treatment. For example, he was friendly with The Nanny actress — and current SAG president — Fran Drescher, and when the sitcom star landed on the cover of Hachette’s Elle in 1995, staff suspected that Pecker was behind it.

After Hachette and Ron Perelman’s New World teamed to buy the film magazine Premiere in June 1995, Pecker reportedly pushed it to feature her on its cover as well, much to the chagrin of editors at the time, even though she was a TV star whose most recent film work was the 1994 flop Car 54, Where Are You?.

Pecker explains to me in a statement, “Fran Drescher had the most popular TV show The Nanny. I recommended Fran to both editors. She was also a fashion expert.”

He also developed a reputation for killing uncomfortable stories. A year after acquiring Premiere, the magazine’s business column, called California Suite, was slated to run an investigative story about Sylvester Stallone’s investment in the celebrity restaurant Planet Hollywood. Perelman, though, had a joint venture with the restaurant group, and the piece was infamously killed. The pretext was reader surveys saying they were more interested in film than investigations, according to a 2017 New Yorker profile of Pecker.

Editor-in-chief Chris Connelly and deputy editor Nancy Griffin quit, writing to their bosses, “Because we feel that the editorial integrity and credibility of Premiere is the magazine’s most precious asset, we will not kill Corie Brown’s California Suite column for July as we have been ordered to do by ownership. We therefore resign our positions . . . effective immediately.”

Although this practice later became known as “catch and kill,” back then, as one former magazine executive tells me, everyone was buying up pieces that wouldn’t run. Harvey Weinstein, the former movie kingpin now in jail, was a big proponent of acquiring and paying for material for possible script to screen adaptation to keep people quiet.

Pecker denied any influence from Perelman at the time.

Samir Husni, a former professor at the University of Mississippi’s journalism school, was a consultant to Hachette at the time. He worked closely with the late executive-VP and editorial director, Jean-Louis Ginibre, who kept a close eye on Pecker’s interference. “The French were watching 24-7. There was a liaison, Ginibre. They were 100 percent in control of the editorial,” says Husni. “Pecker always referred to me as The Professor. He invited me to speak at Hachette and introduced me to John Kennedy. I was in awe, and [Kennedy’s] telling his staff, ‘You have to listen to [Husni].’ It was an awkward moment.”

Trump Bump

During Pecker’s reign at Hachette, he got closer to Trump, the two crossing paths in Florida where they both had homes. Trump would call up publicists to get himself invited to New York magazine parties, a former magazine executive tells me. “Donald Trump wanted to be around anybody who was more famous than he was,” one former executive says. Drescher, in a TV appearance in 2020, recalled Trump appearing on The Nanny, with him insisting on altering the script to refer to himself as a billionaire, not a millionaire. They settled on “zillionaire.”

Trump was entranced by Kennedy and invited the George team to host a private advertiser event at his Mar-A-Lago estate. Trump sat at a table with Kennedy and Carolyn Bessette. (His wife at the time, Marla Maples, sat somewhere else.) They all listened to New York Governor George Pataki, a Republican, deliver a paid speech.

The first issues of George generated so much buzz that it immediately looked like it could take on much bigger rivals like Vanity Fair and Vogue, as it was so flush with ad pages that it looked like a phone book. Burberry, Chanel and Estée Lauder ads sat on prized right-hand pages opposite interviews with President Clinton’s press secretary, Mike McCurry, and conversations with actress Elizabeth Hurley, an Estée Lauder model. The debut issue sold 97 percent of the 550,000 copies distributed to newsstands.

Perhaps the celebrity magazine formula could be repeated with Trump front and center? By 1997, Pecker and Trump would launch the quarterly Trump Style magazine — and a vanity publishing business was born. Sources say that Pecker was not only a source of industry gossip for his soon-to-be publishing partner, but that Pecker kept the New York Post fed to keep himself out of it (if rarely successfully).

The Tabloid Decade Takes Hold

After the initial excitement died down, Kennedy’s George struggled for several reasons. Some staff believed that Pecker was using Kennedy to drum up ad dollars that ended up at other titles in the company portfolio. As celebrity culture was exploding in popularity, another source of tension at a time emanated from Pecker’s efforts to draw George into an edgier, breaking news realm — and those entreaties falling on the scion’s deaf ears. In 1998, Clinton, Monica Lewinsky, Ken Starr and Linda Tripp filled nightly news broadcasts and headlined newspapers.

Pecker confirms this, explaining in his statement, “I wanted to increase newsstand sales.” (The December 2000/January 2001 issue, after Kennedy’s death, would feature a Tripp exclusive on the cover.)

Sex, scandal and a president, as you can imagine, was a tricky, too-close-to-home subject for Kennedy to grapple with, although the magazine wasn’t wholly averse to winking at it. A 1999 issue guest edited by Ben Stiller featured the There’s Something About Mary star holding a Clinton pencil sharpener with Stiller inserting a pencil into his mouth. (The magazine also broke news about the involvement of Richard Carlson, Tucker Carlson’s father, in helping Lewinsky cash in on her newfound fame.)

Four years down the line, though, George’s budgets were too outsized for the title, which although it had a healthy subscriber base of around 400,000, had yet to make money (not uncommon for a big launch). Kennedy’s friendship with his business partner Berman was fracturing, and Pecker, too, had grown tired of his own lot at Hachette.

Hitching to a New Star

Pecker now had his eye on equity and not just CEO-dom. He stunned the George team with his February 1999 departure to spearhead an Evercore Capital Partners-led group to acquire AMI, the Florida-based publisher of down-market supermarket tabloids the National Enquirer and Star. That year, Keith Kelly estimated the titles were clearing in excess of $100 million per year, but things would soon change in the magazine business and newsstand sales were falling.

With Pecker gone, a new boss took over at Hachette, Jack Kliger. One former Hachette employee said that after four years, Kennedy had tired of the magazine and was preparing to give notice after a weekend away at his cousin Rory Kennedy’s wedding in July 1999. Pecker confirms that Kennedy had told him of his exit plans.

He never came home, dying in a plane crash with Bessette and her sister Lauren.

The staff were devastated but Kliger kept the magazine going a little longer. Just long enough for Trump to get his longed-for George cover treatment, appearing with an unseen woman’s lips kissing his cheeks. The headline: “The Secret Behind Trump’s Political Fling.”

“When I got to Hachette, I was hired with an awful lot of issues, including George and Mirabella,” Kliger told Esquire writer Kate Storey, “and also I was following a CEO named David Pecker who left us with a lot of stuff to clean up.”

Pecker hit back in his statement to The Ankler: “I have no idea what Jack Kliger is talking about. Hachette was very profitable and generated large amounts of free cash flow. I was informed by the Chairman that the U.S. operations were the most profitable company in Hachette’s portfolio.”

George 2024

As Pecker testified at the outset of the Trump trial about his National Enquirer manufacturing the 2016 story about Ted Cruz’s father and Lee Harvey Oswald distributing pro-Fidel Castro fliers shortly before the assassination of JFK Jr.’s father, as well as doing catch-and-kill work for not only the former president but also Ari Emanuel on behalf of his client Mark Wahlberg, as well as brother Rahm Emanuel, Kennedy’s original vision for melding pop culture and politics looks ever more prescient.

George magazine may simply have been ahead of its time. (Was it well-executed? That’s another question.)

Kennedy may have died around the time Trump was playing footsie with a Reform Party run in 2000, but he’s remained intertwined with the 45th president in ways that even the fantastical tabloid Weekly World News (also owned by Pecker’s American Media) never could have imagined. JFK Jr. was a seminal part of the QAnon conspiracy: As its lore has it, Kennedy is secretly alive and working with Trump to save the United States from a sinister faction. Kennedy’s first cousin, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is now running for president against Trump as an independent.

This summer will mark 25 years since JFK Jr.’s death, and his former chief of staff at George, RoseMarie Terenzio, is publishing JFK Jr.: An Intimate Oral Biography to mark the anniversary.

Pecker, who lives in Greenwich, Connecticut, with his wife Karen, exited American Media in 2020. Its ultimate owners, Chatham Asset Management, were never able to sell the National Enquirer despite several attempts. It remains part of A360Media, a company formed from a merger of AMI and Accelerated360, also a Chatham venture.

And in perhaps the oddest twist of all, in 2022, George magazine was reincarnated, owned by Gene Ho, a former campaign photographer for Donald Trump. It is now, in effect, a MAGA-zine: Trump has appeared on five of its 17 covers thus far.

Disclaimer: I am publishing a biography about Rupert Murdoch for Hachette’s Grand Central Publishing.