Israel-Gaza Engulfs Eurovision

Europe's weird singing competition struggles with 2024 reality: War, boos, budgets and boycotts

It’s been a rough week for the organizers of Eurovision — and it’s only getting worse.

Everyone knew this year’s Song Contest would be loaded when organizers, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), refused to heed calls to bar Israel from the show amid its war in Gaza. But the chaotic scenes in Malmo, Sweden, as thousands of pro-Palestine protesters took to the streets ahead of today’s May 9th semi-final wasn’t exactly sparkling PR for an event trying to unify the continent through music.

“Young people are leading the way, showing the world how we should react to this,” Swedish activist Greta Thunberg told reporters at the protest, which saw red and green smoke from flares billowing across the crowd.

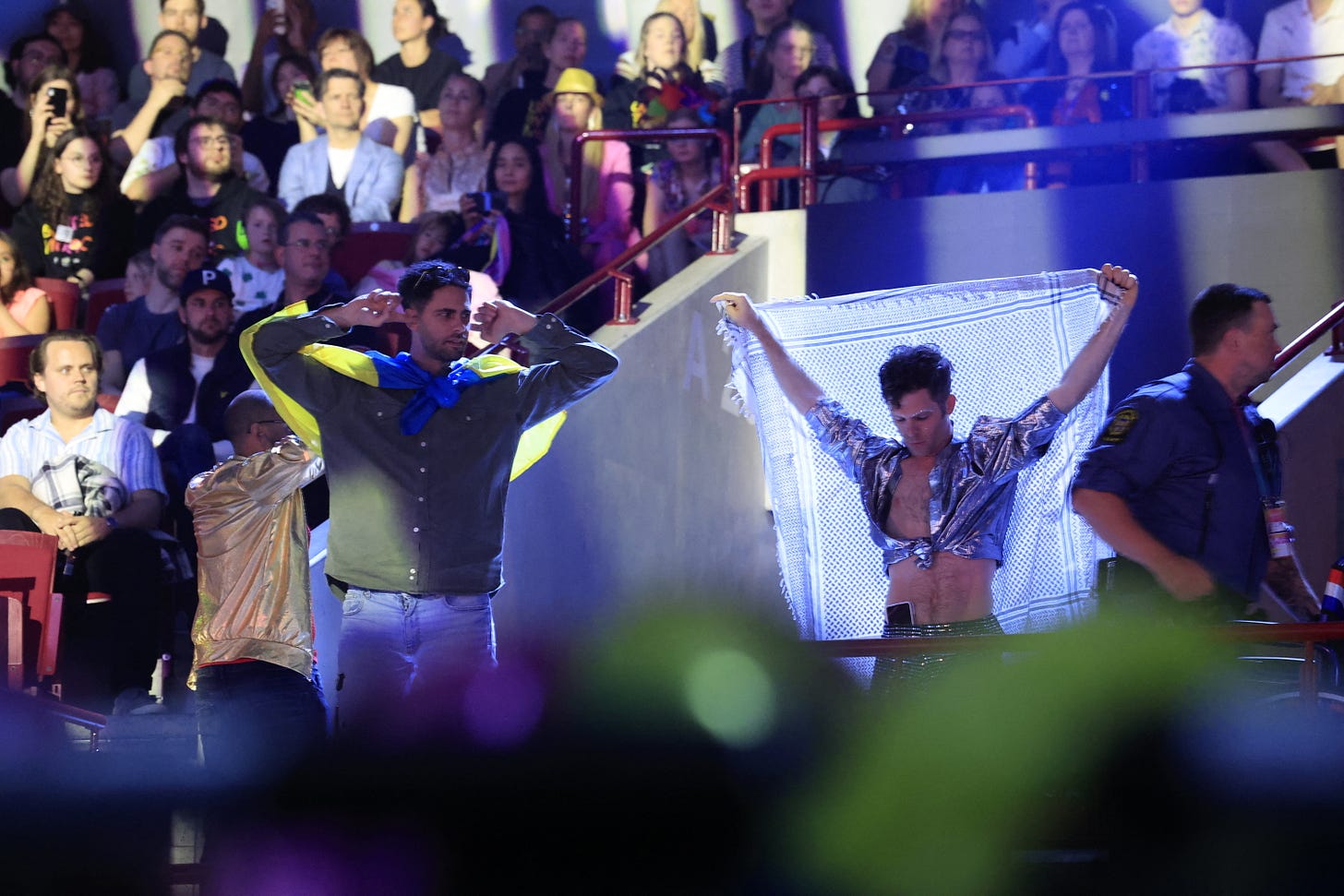

Thunberg was draped in a keffiyeh (a checkered scarf currently associated with the pro-Palestine movement) — the same garment the EBU apologized for when it was worn on stage by Swedish singer Eric Saade at the Tuesday semi-final despite a ban on political gestures in performances.

For years, the EBU has vowed that Eurovision is a “non-political” entertainment event, but as Eurovision scholar Mari Pajala jokes, “Everyone agrees Eurovision is political except the EBU organizers.” In 2022, the org swiftly suspended Russia from the competition after it invaded Ukraine. Its refusal to ban Israel despite the humanitarian crisis in Gaza and the present military action in the city of Rafah seems only to have spurred on protesters at this year’s event.

Founded in 1956 and organized annually by the European Broadcasting Union, the contest sees the EBU’s member countries select artists to represent their nation in a massive live event (the 2022 show cost the U.K. a reported £24 million, or $30 million) broadcast to an estimated 160 million viewers. Each country delivers a single song, and while there are plenty of inoffensive pop ballads, the rule of thumb, for some, tends to be “more is more.” The country with the winning song hosts the next year’s competition.

In 1979, Germany performed a rollicking ode to Genghis Khan. A year later, Luxembourg delivered “Papa Pingouin” with a chilling human penguin frolicking on stage. In 2006, Finnish heavy metal band Lordi gave Gwar a run for its money with the winning “Hard Rock Hallelujah.” In 2012, ethno-pop band Buranovskiye Babushki, comprised of elderly ladies from the Russian republic of Udmurtia, danced around a bread oven. You get the idea.

Still, things are far less lighthearted this year: When 20-year-old Israeli contestant Eden Golan takes the stage at today’s semifinal, she likely will be booed. Golan’s original song was called “October Rain,” a reference to the October 7 Hamas attacks in Israel, but it was deemed too political for the competition and ultimately rewritten as “Hurricane.” At the dress rehearsal yesterday, she was greeted with jeers and shouts of “Free Palestine.”

So, to recap, it’s a politically fraught, expensive, logistical nightmare — and it very, very rarely produces a global superstar. (ABBA and Celine Dion are the most notable exceptions.) Simply put, if the Eurovision Song Contest didn’t already exist, no one would ever greenlight it today.

How then, in today’s content market, does a show of this scale survive? And how will it weather this year’s terrible PR storm?