How to Make ‘Sentimental Value’: Joachim Trier’s Fantastic Four Craftspeople

Plus: The Oscars jump to YouTube, and I have so many questions

Happy Thursday, and please know that if this e-mail is met with your out-of-office notification, I will be thrilled for you. I’ve been banking a lot of podcast conversations over the past few days that you’ll be hearing over the holidays and into the new year, and the overwhelming feeling I’m getting is sheer exhaustion. We’re all so burnt out that even bizarre executive photo ops can be met with a mere shrug.

And yet, there was huge news in the world of awards this week, as the Academy announced a partnership with YouTube to broadcast the Oscars ceremony beginning with the 101st show in 2029. Yesterday, I hopped on Substack Live to talk it over with Natalie Jarvey, author of the indispensable Like & Subscribe newsletter; if you, like me, still feel a little lost in the world of creators, Natalie’s newsletter helps make sense of it all, and definitely helped me feel a bit less blindsided by the Oscars-YouTube news than some of my peers and fellow pundits.

As Natalie emphasizes in our conversation (watch it above), and as we both witnessed firsthand during YouTube’s FYC push for Emmy season, YouTube is seeking respect in Hollywood in addition to its overall cultural domination. So while I guess we may get an Oscars with an added category for creators, or best picture presented by MrBeast, I seriously doubt it. The Academy has been seeking more control over its ceremony after more than 50 years of partnership with ABC, and I can’t imagine the leadership making the bold move of ditching broadcast entirely unless YouTube was offering them some room to run. Being a good steward of the Oscars is an incredibly efficient way for YouTube to earn the respect it’s been seeking.

The first YouTube Oscars are still more than three years away, and there are still a ton of details to be worked out — for example, it’s still unclear to me if the Oscars will be available for free to American viewers, or if you’ll have to subscribe to YouTube TV for up to $83 a month to watch them. But I’m largely in favor of this deal, one of the rare examples we’ve had in recent weeks of a Hollywood institution embracing the future in a way that isn’t terrifying.

I’ll have more to say about the Oscars, YouTube and so much else on tomorrow’s Substack Live, which I’m hosting alongside Christopher Rosen, a live mailbag episode to wrap up the year, exclusively for Prestige Junkie After Party subscribers. (Email me now to get your thoughts in: katey@theankler.com.) We’ve been so thrilled with the community we’ve built on After Party since launching in August, and we’re excited to close out the year with you. Make sure you’re subscribed, and join us here at 12 p.m. PT on Friday afternoon; the conversation will also be available as a podcast episode on the After Party feed.

For the rest of today’s newsletter, join me in conversation with many of the key players behind the scenes of Sentimental Value, which made three Oscar shortlists earlier this week (casting, cinematography and international feature as the submission from Norway) and has been a steady awards season favorite ever since its debut at Cannes in May.

Behind the Scenes

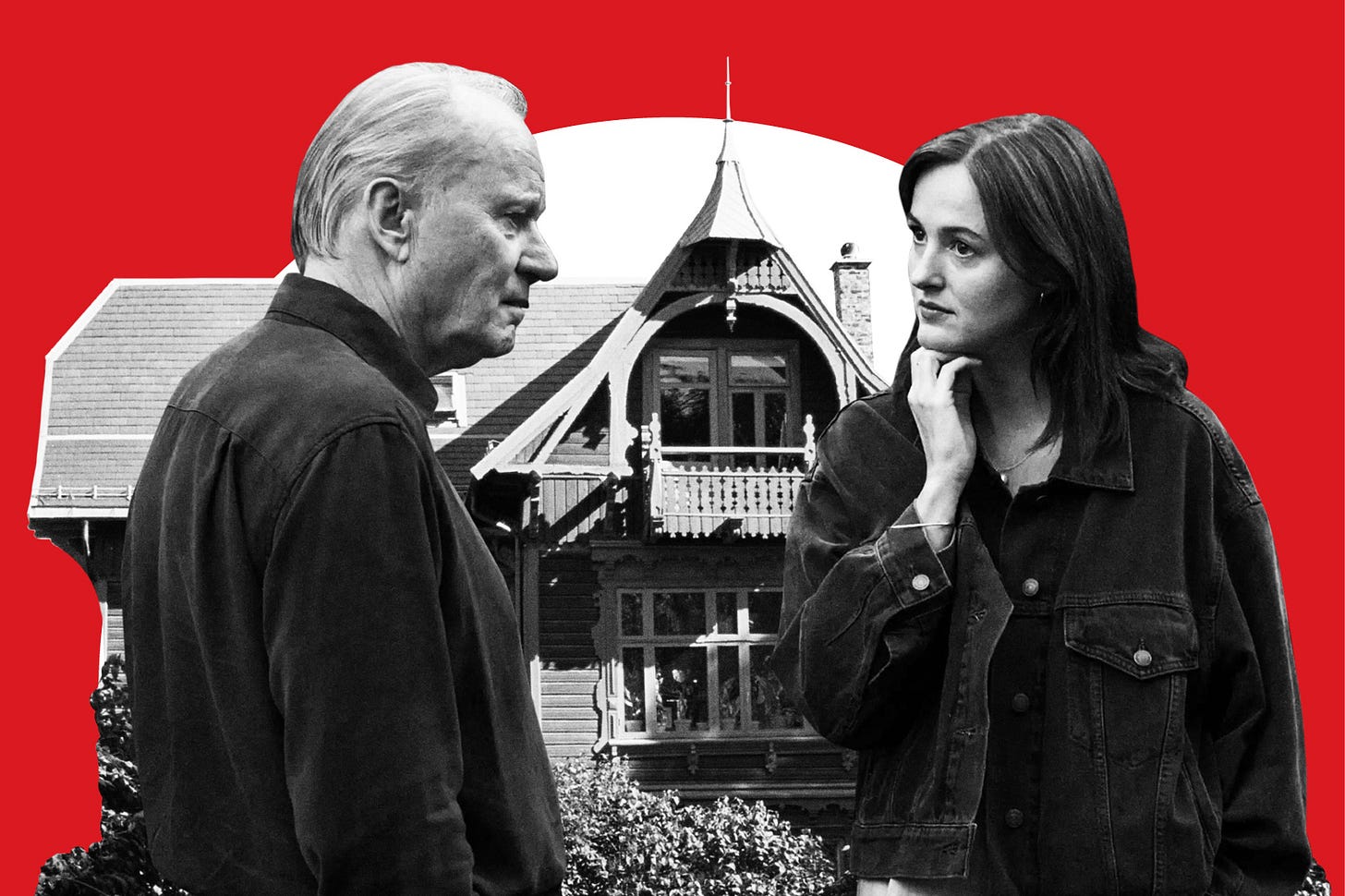

Every film is harder to make than it looks. Still, there’s an absolute effortlessness at the heart of Sentimental Value, the family drama from Oscar-nominated writer-director Joachim Trier about an aging filmmaker who reconnects with his estranged daughters. Starting from the point of view of a house — a real, rickety Victorian home in Oslo — and the sisters who grew up in it, Sentimental Value is a relatively contained story about a few people, most of whom are related. Of all the films in the running for a best picture nomination at this year’s Oscars, it may be among the smallest.

But you have to get every detail right to have a movie this intimate actually work, and that’s what Trier was counting on from his team of collaborators, most of whom have been with him for years, if not decades. In separate conversations, I talked to Trier as well as four key artisans who worked on Sentimental Value — casting director Yngvill Kolset Haga, cinematographer Kasper Tuxen, production designer Jørgen Stangebye Larsen and editor Olivier Bugge Coutté. It was actually an ideal way to put this piece together, as Trier felt empowered to praise his collaborators to the high heavens without any pushback. (“Olivier in particular would say ‘Shut up, man!’’ Trier insists. “He doesn’t want to hear it.”)

Below, the team breaks down many of the key elements that went into making Sentimental Value, out now from Neon, a success — from the casting process that built this family to the editing that helped the story seamlessly link past and present. You can watch an edited version of my conversation with the crafts team, courtesy of Critics Choice, here as well.

Building a Family

Casting director Yngvill Kolset Haga knew from the very beginning that Renate Reinsve would be at the center of Sentimental Value, just as Trier did when he sat down to write the script alongside another of his longtime collaborators, Eskil Vogt. The actress had worked with Trier on two previous films, with a small role in Oslo, August 31 and a career-making lead turn in The Worst Person in the World, an Oscar nominee for international feature and original screenplay in 2022.

But even though Reinsve is the film’s star, with Stellan Skarsgård in a key supporting role as her complex father, this is a family with two daughters. As Haga, who first worked with Trier on 2017’s Thelma, tells me, “Obviously, it was the sister role I knew I would be starting with.”

The actress she cast, Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, is a major discovery, much as Reinsve was in The Worst Person in the World. Haga sums up her work in casting family members fairly simply: “Can we believe these faces can match each other in some way?” For Trier, Haga’s skill isn’t just in the time she spends with her work — he says she spent nearly a year casting Sentimental Value — but in how she engages with his scripts.

“Out of all my collaborators, she’s sometimes the one who asks the most difficult questions, because she is an actor herself,” Trier says. “She forces me to articulate certain motivations, the dynamics of scenes and relationships, because she’s the first front before I even meet the actors properly. I think that’s a really refining, wonderful process. She’s not scared of challenging me.”

The House That Jørgen Built

Much as Trier had already cast Reinsve before production began, he had also selected the house that is central to the story — and he and production designer Jørgen Stangebye Larsen had already put it onscreen for a brief part of Oslo, August 31st, their first collaboration.

“I actually knew the house, and when I read it, I kind of had it in my mind,” Larsen says. But Sentimental Value spans many decades, with flashbacks and scenes set in the past, and to capture all the different eras, Larsen built a replica of the house on a soundstage, where it could be moved from the 1930s to the present and back again.

“I found some real images of the house that were very helpful,” Larsen explains. “I also connected all the time periods to the characters living there, and when it would be natural to have a change and when not to have a change.” As different characters own the house, it changes, as it would in real life; actually, the set standing version of the house did change in real life.

In a scene set in the 1980s, we see Skarsgård’s character, Gustav, renovate the house he grew up in and tear out wallpaper, revealing generations of previous wallpaper underneath. That was Larsen actually building over the 1930s version of the set he’d already created; as Trier says, “he didn’t only change it out, he put it on top of each other as you would in a real house, so that we could do all this tearing down and get this feeling that it was an old house.”

“Thank you, Jørgen, for taking my directorial neurosis so seriously,” Trier continues. “That was really fun for me, and I’m really eager to do more period now that I’ve gotten a taste of it.”

‘As Old as Cinema Itself’

Cinematographer Kasper Tuxen, too, went deep into historical detail in his role in capturing this house and the people who lived in it over the years.

“Realizing that the house was as old as cinema itself, it felt natural to tell the story of the house through the growing up of the cinema,” Tuxen tells me. “Starting in black and white, we showed a little bit of 16mm, but that was just to get the right vintage grain for the first chapter of the house. And the rest of the film was shot in 35mm, and we played with time-accurate lenses through the period Jurgen just described.”

“We did a lot of research — we tested and tested,” Trier adds, a process of experimentation that Tuxen describes as “a fun game to play.” Tuxen worked closely with Larsen not just to accurately capture the time periods he’d created, but to logistically move the cameras through both the real house and the soundstage version. As Tuxen describes it, “Jørgen would make walls and doors that hinged, or sand floors so we could do a slide with the dolly with no thresholds.”

Trier has the most praise for Tuxen’s skill in working with actors, not just in creating an environment in which they can do their best work — “He’s anti-macho,” Trier says, clearly a huge compliment — but capturing subtleties of performance that other cinematographers might not even notice.

“The reason I still shoot 35 is the face,” Trier says. “These actors are so sensitive in their acting that you see their color change in Renate’s cheeks. Sometimes people don’t get how good Kasper is, because he’s amazing at capturing the emotionality of natural light, performance, human skin tones and the difficult balancing of neutral color palettes. I don’t mean to be arrogant, but do they get how tricky it is to do that neutral balance?”

Cut to the Feeling

Editor Olivier Bugge Coutté has the longest working relationship with Trier, having met when they were in their early 20s, even before they were both accepted to the highly selective National Film School in London.

“When Eskil and I write, and I shoot, I think about Olivier,” Trier says. “He’s in my mind because I know what he does very well is two things: he’s very good at structuring montage sequences in kind of philosophical and fun ways, and he knows how to make dynamics of events and non-events like a musical structure.”

That’s a little abstract, Trier admits. But when he and Coutté talk about things like “musical dramaturgy,” Trier mostly means he wants to keep the audience as engaged as if they were watching a traditional blockbuster. “We have one foot in an American tradition, where expositions have got to be fucking entertaining, or people won’t watch your film.”

In Sentimental Value, that exposition happens in that opening montage, with a woman’s voiceover telling the story of the family’s life from the perspective of a house. (The actress who provides the narration is Bente Børsum, who worked with Trier’s grandfather, the filmmaker Erik Løchen, on the 1959 movie Jakten.) It’s a clever idea that immediately draws you in, but presents a kind of wild challenge for an editor. So “instead of cutting on the action when people enter the frame and exit the frame,” Coutté explains, “we left the frames empty, as if the house was still there before they came and after they left.” It’s the opposite of how almost every other film is edited, but it has precisely the effect Coutté describes: “It’s like you are in the belly, you’re in the brain of the house. You’re in the eyes.”

As with everyone else on his team, Trier emphasizes how much Coutté’s editing contributes to the performances at the heart of the film. “I think this recurs with all my collaborators — that they care about human stories and character behavior,” he says, before recalling something he learned from director Stephen Frears when Trier was a film student in London.

“We often talked about how when actors win awards, they should remember also to thank the editor,” he says. “That’s a very close collaboration. And good actors know.”