How Ozempic Ate Awards Season

Plastic surgery upended, pre-workout puking, half-eaten plates: scenes from the strange havoc of Semaglutide Hollywood

“This year’s Oscar for Special Achievement in Motion Pictures goes to . . . Semaglutides!”

Two giant syringes, one labeled Ozempic, the other Mounjaro, take the stage to the tune of “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

“Thank you, Academy.” Ozempic begins. “You’re looking good. My colleague and I know why. You know why. Everyone actually knows why. Because as I look at this naked statuette with its sleek midsection, evident cheekbones and cottage-cheese-less thighs, I see an ideal of beauty which we have made available to all of you here in the Dolby Theatre — and those few of you watching at home with ample money and willing doctors.

To all of the Hollywood plastic surgeons, stylists, personal trainers, makeup artists and chefs whose livelihoods we have altered — and yes, in some cases ruined — let me conclude by quoting what Cate Blanchett said to Julia Roberts upon winning the Best Actress Oscar in 2014: ‘Hashtag Suck It.’”

Thank you! Now who wants a shot?”

Forget Chanel, Dior or Prada: This year, the most prominent designers on the red carpet are Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, whose injectable weight-loss drugs are the new couture. As awards season peaks this weekend with the 96th Academy Awards, those in every cranny of the celebrity-industrial complex, from restaurateurs to marketing mavens, have found themselves dealing with profound changes wrought on entertainment industry bodies and minds by this new kid in town. In the old days — five years ago (and five decades ago) — you’d get someone into rehab or to Two Bunch Palms to dry out and get in shape for a big role or a red carpet. Now a star can quickly lose up to 15 pounds (or more) in plain sight.

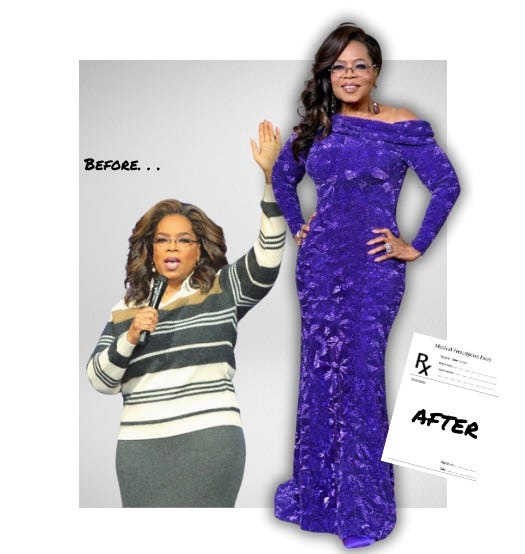

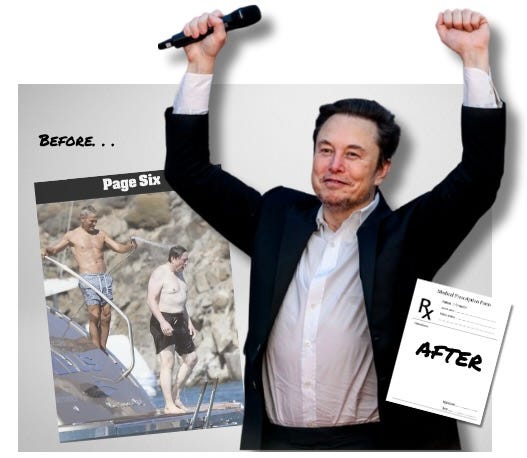

Only a handful of celebrities — Oprah Winfrey, Elon Musk and Tracy Morgan are the most prominent — have publicly acknowledged using this new class of drugs, known as semaglutides, GLP-1s or by their brand names Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro. A few other famous people, such as Amy Schumer, Chelsea Handler and Sharon Osbourne, have admitted to using these drugs in the past, and an even smaller subset is using them for their original purpose of helping type 2 diabetics (Anthony Anderson). Indeed, a whole separate cottage industry has popped up of people denying or condemning the use of them.

Julia Fox told Entertainment Tonight, “People are saying that I'm taking Ozempic. I'm not, and I never have. I would never do that. There are diabetics that need it." Jessica Simpson denied to Bustle that her weight loss was injection based, saying “Oh Lord . . . it is not.” Most judgy of all was Vanderpump Rules’ Lala Kent, who may be thin in the old-fashioned way, possibly so hungry that she recently bit the hand that feeds her. “Stop taking it for weight loss,” she told People. “Enough already. I think that Hollywood is all sorts of f—ed up.”

So in honor of the Oscars, let’s look at the impact on restaurants, plastic surgeons, trainers and makeup artists around town of a drug turning Hollywood into wannabe Barbies and Kens:

Trainers: Clients Stuck in the Bathroom

“The closer we get to the day of the awards, my clients who focus on the Oscars, sometimes they will come in and they’ll be sick in the bathroom for 10 minutes with diarrhea, nausea, constipation, dizziness,” says Karen Miller, a private fitness coach with 43 years in the business. Miller, who has worked in the past with Joaquin Phoenix and Casey Affleck, is annoyed by current clients who increase their doses of miracle weight-loss drugs and suffer side effects. But if the clients want to pay for the extra sessions, so be it. “When you get closer to the Oscars, they up their dose a little bit. They think the more you take, the less hungry you will be. The reason one of my guys went from three to four days a week is we weren’t able to get the full workout in.”

When Miller arrives at the house of a very famous female client, she’s often met by a housekeeper saying the client needs those 10 extra minutes before coming down. “She’s in the bathroom, or she’s drinking ginger tea to make her nausea go away.”

These are not obese people.

“The three I know who are on it, they don’t really need it,” Miller says. “But a doctor in Los Angeles will give you anything you want.”

Restaurants: 'Nobody is Hungry’

The most direct suffering is being felt in the food world.

Paul Vitagliano and Billy Harris are known for putting on charity food events all over town. In fact, Harris leads the annual auction at the Alex’s Lemonade Stand event, to benefit childhood cancer research, at which Oscars host Jimmy Kimmel has for years offered up dinner for a group at his house cooked by celebrity chefs like Nancy Silverton and Chris Bianco — a prize that can fetch $100,000 and more, all for the charity.

“We've observed a notable change in consumption patterns at the celebrity-attended events and galas we've produced this season in Los Angeles,” says Vitagliano, cofounder of the Ombrello Agency. “Meals are often only partially eaten. At first our chefs were thinking something was wrong with the food. However, it’s clear that many attendees are opting for significantly smaller portions.”

L.A. restaurants are already suffering from rising food costs, staffing shortages and regulatory hurdles (never mind the losses suffered during the strikes). Now, decreasing appetites from some of the formerly highest-spending customers are hitting hard. “There are very prominent restaurant customers I know who are tied to the movie industry and investment worlds and who used to go to restaurants and order half the menu,” says Andy Wang, an award-winning food writer who throws private, industry-only parties for chefs and restaurant operators. “And when I go out with them now, they don’t do that. They order less, they order in moderation, and even when they order less, you can see they are leaving it on their plates.”

Worse, they’re not ordering desserts, dessert wines, and espresso where a lot of profit is.

“I play in this poker game full of entertainment guys,” Wang says. “People would bring stuff from Joan’s on Third, some sick order from Jon and Vinny’s, Sugarfish. And now you go and nobody brings shit, and nobody complains because nobody is hungry.”

Plastic Surgeons: Bye-bye Lipo

Dr. Suzanne Trott is the “Lipo Queen” of Beverly Hills. More than a decade ago, Trott was the first plastic surgeon in Southern California to perform fat transfer breast augmentations — the procedure where fat is harvested from the stomach, hips, thighs, back or arms and injected into breasts, where it stays permanently. Trott still does it, but the hunt for fat is harder on an Ozempic-slimmed body. What’s more, the liposuction body-sculpting sessions she used to get $15k for in-office and $30k for the procedure with anesthesia in a hospital are not selling like they were.

Out: Full liposuction.

In: Post-Ozempic “body contouring,” which is basically the post-weight-loss mop-up procedure.

Trott is sanguine about more rarely unholstering her fat vacuum and cannulas. “It’s less manual labor for me, to be honest,” Trott says.

Also of questionable necessity these days is Trott’s line of body-sculpting clothing, Lipo Queen Shapewear, that she says has been worn by Jennifer Coolidge and Amy Poehler (when she hosted the Golden Globes). Perhaps Novo Nordisk can somehow adapt Trott’s shapewear ad copy for its own marketing: “It fits like a second skin, smoothing out your bra fat, back fat, saddlebags and inner thighs.”

In the old days, you needed to leave six months between a procedure on your face and your public debut of the new visage in order to make sure all the swelling was gone. But now, with Ozempic, the timing is almost a year out: You need to lose the weight, then do the anti-Ozempic-face surgery to tighten freshly fat-free jowls and lipidless eyebags — and then still leave six months to spare before walking the red carpets of awards season without raising (if Botox allows) eyebrows.

During that six months, you also need to work with your personal trainer to build back some of the muscle tone you might have lost (one of the most common side effects of semaglutides), all while staying on the weight-loss drugs to avoid rebound weight gain. It’s a lot to fit into a schedule if you’re planning on actually acting in, say, season four of Loudermilk, or if you’re an executive jetting around trying to figure out how to simultaneously produce less content and raise the subscription price for your streaming service.

If you don’t want to leave the internet wondering why you look so puffy, saggy or sallow in a bad way, you’ve got to plan. “That’s the problem with people, not just celebrities,” says plastic surgeon Dr. Kelly Killeen. “They don’t plan. They are not thinking of all this. They want to look great immediately and be on the red carpet. It’s not that simple.”

Stylists: Shrinking Clients, Good for Business

George Kotsiopoulos, a stylist best known for being on Fashion Police, shares this Lagerfeldian nugget. “All Ozempic is about is looking better in your clothes,” he says. “Who has ever lost weight and said, ‘Dammit, I don’t look good in my clothes anymore!’ Who has ever said, ‘Dammit, you can see my waist now’?”

The lawman’s point is that for at least one cog in the red carpet machine — the fashion stylist — Ozempic is a net gain that makes life easier. “If you are a stylist,” Kotsiopoulos says, “and your overweight client has suddenly lost 50, 60, 70 pounds, you are going to be very happy. It’s easy to style someone who is a size 14, but once you get into 18 and not having a waist, round shaped, it’s very hard to find clothes that look good.”

That said, the power of glucagon-like peptide can make a stylist stressed out if a big star does a couture fitting a month out from an awards show and doesn’t share that they might be two sizes smaller on the big day. Alteration needs can be severe. “If they are going from size 14 to size 12 in one fitting, I would be pissed,” Kotsiopoulos says. “But you always have to do tweaks anyway.” Conversely, the drugs can allow someone to more confidently declare of a snug garment that there’s no need to alter it. “If they fit for a dress and the dress is tight, they’re going to say it will fit by the Oscars. I will lose these five pounds.”

Makeup Artists: Ozempic Isn’t an Enemy

Another awards-season staple not suffering: makeup artists.

Deborah Esposito has been doing the job for 30 years, including in the old days for elaborate magazine shoots by such photographers as Annie Liebowitz and Herb Ritts.

“It’s not like it used to be,” she tells me.

“It sure as shit is not,” I reply.

Esposito says that she has industry clients in their 60s, men, who have used Ozempic to shed a stubborn 10 pounds. “They look less bloated,” she says. There may be studies that suggest GLP-1s can lower cholesterol, reduce addictive behavior and treat mental-health conditions, but you know what they can’t do? They don’t yet turn gray hair brown. For less than $200, Esposito does. “I do brow and lash tints and wax their face. Those guys come in every three weeks.”

For her, Ozempic is just another thing that came to L.A. Like cocaine and smashburgers.

“The only thing that affected our business was Covid,” Esposito says.

Jesika Miller, a makeup artist who works on print advertising and editorial still photography, says that colleagues on film shoots are gabbing about resorting to old-school techniques to deal with the thinner and looser skin that can come post-Ozempic but pre-surgical intervention. “Joan Crawford had a clip she put on the back of her neck to pull her skin tight,” she said. “Now, there’s face-taping for a short-term solution, or some people just tie their hair back very tightly for a quick face-lift.”

This is less prevalent in the advertising world because models are hired not for their fame or box-office pull, but for the way their appearance fits into what a client needs that week. “In the world I work in,” Miller says. “They wouldn't be hired if they were a plus-sized model and they showed up for the audition and they were not a plus-sized model anymore.”

On Top of That: The Get-Thin, Get-Jacked Cocktail

Along with all these changes, there is an undercurrent of fear that there will be some bold-faced tragedies. Who will be GLP-1’s Karen Carpenter?

“There is a genesis of new miracle drugs that come out. There’s an excitement at first and then there’s backlash as the reality sets in,” says Dr. Kenny Spielvogel, a physician at Carrara Treatment Wellness & Spa, a luxury drug and alcohol rehabilitation center. He points out that researchers are already exploring a link to thyroid cancers, potentially bad interactions with other medications and other side effects, including what happens with long-term use. “I heard a metabolic expert from Harvard say these drugs have the potential to poison your metabolism if you’re not doing exercise with them.”

Spielvogel warns of the new and dangerous business that has popped up on the internet: the dispensing of drug cocktails that supposedly enhance the results of Ozempic and Mounjaro. Many entertainment industry people who want to retain muscle mass while on weight-loss drugs are simultaneously taking testosterone, growth hormones and steroids — especially dudes who are bypassing in-person doctors.

An in-depth article in Men’s Health titled, “The Cheat Code to Shredded,” dropped the bomb on potential side effects of combining semaglutide and testosterone, including “increasing the possibility of blood clots, heart attacks, and strokes. Both can also cause pancreatitis, a painful inflammation of the pancreas that could put you in the hospital. In serious cases, it can require surgery and even be fatal.”

When he looks at Jeff Bezos, 60, Spielvogel sees a man who is doing . . . something. (To be clear, the following is speculation. He doesn’t know Bezos’ regimen, nor do I. But Spielvogel is a doctor who has been following all of the weight-loss drug developments closely.) “When you see Jeff Bezos walk around and see what he looked like [when younger] . . . it’s highly unlikely that a multibillionaire didn’t have some help,” says Spielvogel. “You don’t get jacked and ripped and have a 30-inch waste — it’s possible but very difficult to do when you move into your late 40s and 50s.”

How does one hypothetically achieve that look? A routine that includes “testosterone, cyclic growth hormone, peptides, a trainer, daily workouts, and highly protein-based eating,” Spielvogel says. "It’s a simple formula. You see a lot of guys with that appearance.”

And it’s not just guys. Miller, the private fitness coach, said she had a female client taking Ozempic along with the anabolic steroid Winstrol. Along with potential side effects like decreased sexual desire, acne and nausea, the steroid has benefits. “It cuts you. It causes your skin to thin. It will lean you out,” Miller says. “She was taking both of these, right after a big breakup. In her case, it did not affect her workout. She looked really good.”

It’s not to say this wasn’t a path the Oscars weren’t already on, with seeds planted decades ago.

Bob Hope, the comedian who hosted the Oscars a record 19 times — and did not live long enough to see the invention of Ozempic — once said, “The older you get, the tougher it is to lose weight, because by then your body and your fat are really good friends.” Billy Crystal, who hosted the second most times, nine, long ago played a character on SNL who dispensed the following satirical Hollywood advice. “It is better to look good than to feel good.”

See you in the bathroom at the Dolby!

Great piece!