Hollywoodland's Jews: 'Dreams and Fears, Always Fear'

Two years ago, I interviewed Neal Gabler, a harsh critic of an Academy Museum omission. With its new exhibit, the author, still unsparing, helped tell the complicated story

Andy Lewis writes The Optionist, our weekly newsletter about IP. He also is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, and has thoughts on what happened with its president and protestors, but that’s for another day.

“Where are the Jews?”

When the Academy Museum first opened in September 2021, that was the immediate conclusion of Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan Greenblatt as he wandered around the museum during the opening night gala with a friend.

He was not alone in feeling like the importance of Jews in the founding and history of Hollywood had been minimized, especially in contrast to care given to represent other historically marginalized groups, including Black and Asian Americans, Latinos and women. There was nothing for Jews akin, say, to the exhibit on the pioneering Black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux or as powerful as the empty box representing Hattie McDaniel’s lost Oscar.

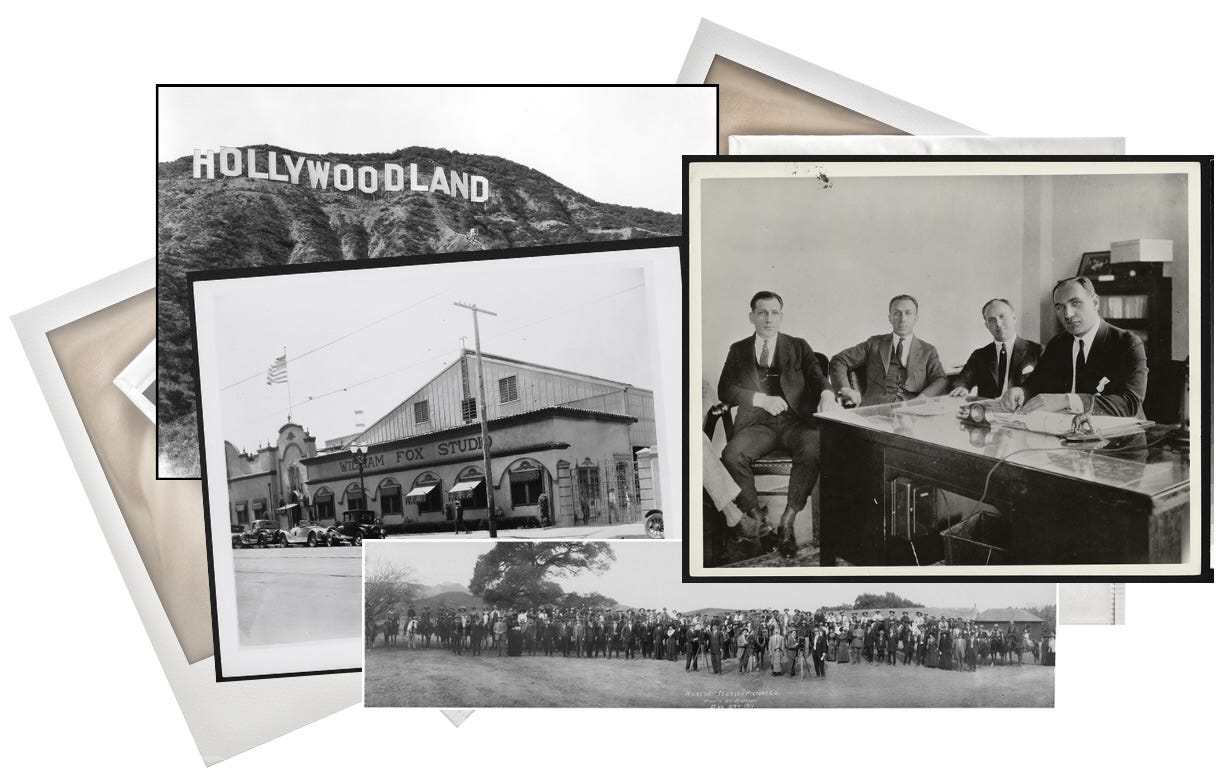

Late last month, the Academy Museum debuted a new exhibit — “Hollywoodland: Jewish Founders and the Making of a Movie Capital” — that aims to cure that omission. The exhibit, largely drawn from Neil Gabler’s seminal book, An Empire of Their Own: How The Jews Invented Hollywood, focuses on the mainly Eastern European Jewish immigrants who founded or ran the eight formative major studios, men like Carl Laemmle, William Fox, Jack Warner, Sam Goldwyn and Louis Mayer.

I toured the new exhibit on May 16 and went to a panel on May 19 featuring Gabler, then-Academy Museum director and president Jacqueline Stewart and curator Dara Jaffe to see how much it addressed his original concerns. (A few days later, it was announced Stewart was returning to the University of Chicago faculty, to be succeeded by Amy Homma.) My last name might not be Mayer and my only tenuous connection to Hollywood was Oscar-winning actor Jack Albertson, a distant cousin. But I understand the often tortured story of Hollywood's Jewish founders, wrestling between identity and assimilation. As a child, prep school bullies in my WASP-y Boston suburb would roll pennies down the hallway for me, one of the only Jews, to chase. It wasn’t always that bad, but I never felt like I truly fit in. Not there, or later at Penn, the most Jewish of Ivies, where I realized aspiring to assimilation had rubbed off on me more than I realized. I was too Jewish for the WASPs; too WASP-y for the Jewish kids. Only as an adult, I understand more why I was so drawn to study for a PhD in African American history as proxy for my own conflicted identity.

As I went through the exhibit, I understood the story of the Jewish founders is my story. I just wish there had been more.

An Empire of Their Own

When the controversy first broke in 2022, I interviewed Gabler, who told me that he believed the museum’s failure to tell the Jewish part of the story was not necessarily just an oversight.

This passage from my interview was really something and stuck with me.

In Gabler’s own words:

The whole idea of the industry when these Eastern European Jews founded it was that Hollywood would be their conduit into America and that the ‘Jewishness’ would be something that they could shed. That's embedded into the very idea of Hollywood. In some ways, the notion that Hollywood wants to put some distance between itself and its Jewish founders is completely compatible with the Jewish founders themselves. When I submitted the book, it was called An Empire of Their Own and the subtitle was “How the Jews invented Hollywood.” I can’t tell you how much resistance there was. My publisher, which was run by Jews at the time, had great hesitancy in putting that on the cover. They negotiated with me to see if we could change the subtitle and remove the word ‘Jewish’ from the book. So the book itself became an object lesson in the very subject of the book. We went through virtually every permutation of the word ‘Hollywood’ and ‘Jew’ that I could possibly think of until it finally occurred to me, as they rejected all of these things, was that they didn't want the word ‘Jew’ anywhere near the book. This is all part and parcel of the process of the formation of Hollywood and the formation of American identity.

But he assigned some of the lost message to the history of ambivalence among Jews themselves to tell their own story through the last 100 years, partially “out of the fear that they might be called out as Eastern European Jews,” who, in contrast to earlier arriving, better educated and somewhat “higher status” German and Austrians Jews, often found themselves at the bottom of the antisemitism pile. They were outsiders even among outsiders. Add the horror of the Holocaust and the anti-communism of the Blacklist Era (“a kind of camouflaged antisemitism” in Gabler’s words), and it was, he said, a battle “fought internally within them and within the studios,” between “their own Jewish DNA and their own desire to be ‘American’ rather than ‘Jewish.’”

The omissions upset him because this kind of amnesia, he believed, had only fueled the rise of the sort of antisemitism we see today. “When you're hiding something, people think you have something to hide,” he said at the time. “When you come clean, you get rid of that wariness.”

‘Dreams and Fear, Always Fear’

I was very excited for Hollywoodland. I was seeking guidance, some better way of understanding my own eternal dilemma of being both Jewish (my maternal grandparents were Russian shtetl Jews who came here around 1900; both my parents were raised in kosher homes and spoke Yiddish) and American, especially in these troubled times when so many American Jews are engaged in emotional conversations about the meaning of both those words and asking questions like, where does legitimate criticism of Israel end and antisemitism begin? Consider how Ari Emanuel’s call for a two-state solution and criticism of Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu was received at the recent Simon Wiesenthal National Tribute Dinner (boos and walkouts). The questions keep bubbling up within me: How can one fight antisemitism at home without getting tangled up in events abroad? Is America even still a welcoming safe haven for Jews?

Imagine now seeing Gabler, both critic and historian, in the belly of the beast.

Gabler asserted during the panel that countless times he was an “asshole” to make sure the museum didn’t “bury the lede” by once again minimizing the Jewish role in the founding Hollywood.

To which Jaffe replied, with a nervous chuckle, “We wouldn't want you to be any different than you are now.”

Still, much of the exhibit feels like a compensatory response to the criticism the museum received when it opened — Hey look, it’s Jews! — a product of the contrast between Gabler’s passion and the museum’s cautious uncertainty. This is best epitomized by the dutiful wall of individual biographies of studio founders. So much of the story of Jews in Hollywood feels held at arm’s length.

Other parts are better. To start, there’s a lot of context about the antisemitic culture of the United States that sets the stage for understanding how movies, originally considered a low-class form of entertainment, became a space open to Jewish entrepreneurs. Discrimination wasn’t a bug in Hollywood success, it was a feature.

Taking its cues from Gabler’s excellent book, the exhibit delves into the mix of assimilationist desires and persistent fears of recurring antisemitism that drove both what was on screen and how the founders lived their private lives. On screen, these studio bosses created both an idealized America (idyllic small towns, upstanding public servants, loving nuclear families) and reinforced its worst impulses: These movies were populated almost solely by white, implicitly Christian, native-born people, the creation of “perfect” Americans.

“Hollywood is the product of dreams and fear, always fear,” Gabler said. These myths became foundational to Hollywood and by extension foundational to the country. It’s such an important point that we don’t get enough of, especially in how it shaped so much of the American Century.

Off screen, they projected a fierce patriotism (not knowing his actual birthday, Louis Mayer chose July 4th) and an unrelenting desire to assimilate. As Gabler noted, “They all divorce their wives to marry Gentiles, and all the Gentile women they marry are the blondes that look like the Gentile women on the screen.”

Still, a View Solely From the Top

I wish there were more on Jewish influence on Hollywood beyond the founding bosses. Where are the Jewish comedians like Groucho Marx, George Burns and Jack Benny? Where are the Jewish actors who also Americanized their names to fit in: to name just three, Al Jolson (born Asa Yoelson), Kirk Douglas (Issur Danielovitch) and Paulette Goddard (Marion Levy)? Or Jewish directors such as George Cukor and Billy Wilder? Where are the below-the-line Jewish crafts people and the Jewish labor leaders?

Focusing predominantly on the Jewish business leaders of Hollywood — no matter how much you nod to their influence on content, some of which is nuanced and compelling — unintentionally reinforces some old stereotypes that emphasize Jewish business success.

I would have liked more, much more, on how the Jewish vision of an idealized, re-imagined America, and the interpretation of their own culture on screen, influenced the American narrative. These myths became foundational to Hollywood and by extension foundational to the country — a fun house mirror now viewed through politics as a reality we must “return” to. It’s an important point that we don’t get enough of in the exhibit. There’s a straight line that can be drawn to Spielberg’s early sentimentalized suburbs and iconic American “good guys” that would have been worth exploring. While no exhibit — or museum — can cover everything, the turn away from Jews’ cultural influence feels like another missed opportunity. It’s also a pity the exhibit doesn’t fully carry the timeline forward to really include the Holocaust, the blacklist and their aftermath on storytelling.

While Hollywoodland does many things admirably well, it doesn’t — maybe couldn’t — respond to the moment we’re in (an impossibility it would seem given the fast-moving events since Oct. 7). It lacks urgency, passion and a sense of the link between then and now.

Interestingly, during the panel, I thought Jaffe carefully chose her words to avoid current events. “There is a very specific historical story as to why the founding of Hollywood is a Jewish immigrant story, and that’s all we wanted to do was tell the very straightforward, accurate history of that,” she said. (The words “Gaza”, “Rafah”, “campus protests” or “hostages” were never uttered. Certainly not “Netanyahu.”)

At the same time, she wanted to reassure the audience that the museum hopes it “can dispel harmful antisemitic stereotypes and conspiracy theories about why and how the Jews invented Hollywood.”

As Gabler himself noted again, American Jews themselves bear some responsibility for the silences. Silences that reflect Jewish Americans’ own uncertainty about their overlapping identities, uncertainties that reflect the same hopes and fears that motivated Hollywood’s founders. “We, Jews, often are afraid of being proud,” said Gabler, nodding to fears that pride could spark (more) antisemitism. “We ought to embrace it. Those of us who are Jewish, we ought to be damn proud of the Jews who invented Hollywood.”

We’re still struggling to figure out how the identities of Jewish and American fit together. I know I am. How Laemmle and Mayer and Fox (and so many others) navigated those challenges can be a guidepost for American Jews and a reminder for others that Jewish success has always been intertwined with antisemitism.

That perspective only underscores why a more fulsome version of this story has never been more relevant. Jews today are navigating the most perilous and uncertain terrain since Hollywood’s founding more than a century ago. Our loyalties as Americans are questioned, our successes seen as dangerous — just as theirs were. (Note Donald Trump assigning blame for his conviction to “George Soros” this week, days after his Truth Social account posted, then deleted, a video promoting a “unified Reich”.)

Ironically, the words that come to mind are not those of a Jewish writer but rather my favorite goyishe one — William Faulkner, who came out to Hollywood to make a buck (and mostly failed at it). “The past is never dead,” he wrote. “It's not even past.”

It's a pity that at this moment when so many are struggling to figure out what to do or even say, the museum couldn’t be more bold in connecting the past to the present.

As Gabler told me two years ago: “There are few greater stories in modern American history than the story of a bunch of seemingly ignorant Eastern European Jews creating the motion picture industry.”

Please, tell us more.

I learned years ago - pre 2000 - that Hollywood was about Eastern European Jews providing a Protestant America with a Catholic morality. And that’s pretty well known I thought.

The main problem is that they apply a different standard to Jews that they didn't apply to anyone else in the museum - which is the very definition of antisemitism.

Did they mention that Pedro Almodovar tortured bulls on his film MATADOR? No.

How about Spike Lee's Jewish caricatures in Mo Better Blues?

Or Bruce Lee's womanizing?

Or the founders of BLM being accused of embezzling $10M?

Their claims of "well this is accurate, or for context" is complete bull pucky. It's hateful. Why would blackface even come up in an exhibit about Jewish contributions to cinema??!!

DO BETTER!!!!!