'Gone With the Wind': The Explosive Lost Scenes

A never-revealed war over slavery's depiction. Rhett Butler's suicidal intentions. A rediscovered script reveals what didn't make final cut

David Vincent Kimel is a historian completing his PhD at Yale, where he also coached the debate team. Read more here about his background and history with Gone With the Wind.

“It was better to know the worst than wonder.”

― Margaret Mitchell, Gone With the Wind

At the Atlanta premiere of Gone With the Wind on December 15, 1939, the 10-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. was dressed as a slave. It was the second night of an official three-day holiday proclaimed by the mayor of Atlanta and the governor of Georgia. King’s choir was serenading a white audience, directed to croon spirituals to evoke an ambiance of moonlight and magnolias for the benefit of the movie’s famous producer, David O. Selznick. He was the son of a former studio head and the husband of Louis B. Mayer’s daughter Irene, inspiring the ancient joke in Hollywood that “the son-in-law also rises.” But he’d fought hard to carve out his own legacy, beginning with his addition of the eye-catching but meaningless “O” to his name, and culminating in his creation of an independent studio. By 1939, Selznick had established himself as one of Hollywood’s most notoriously ambitious and outspoken showmen. He’d gambled his entire studio on Gone With the Wind, banking on the popularity of a novel about a ruthless Southern belle during the Civil War that had swept America three years earlier, winning its first-time author Margaret Mitchell the Pulitzer Prize and soon becoming the bestselling work of fiction in the country, second only to the Bible in book sales.

As Selznick watched King and the Ebenezer Baptist Church choir sing, and white Atlanta swirl around in giddy celebration of his epic movie, the producer harbored a shocking secret never revealed until today: a civil war that had roiled the production internally over the issue of slavery, with one group of screenwriters insisting on depicting the brutality of that institution, and another faction, which included F. Scott Fitzgerald, trying to wash it away. Selznick’s struggles over the exclusion of the KKK and the n-word from the script and his negotiations with the NAACP and his Black cast are the stuff of legend. But the producer’s decision to entertain scenes showcasing the horrors of slavery before deciding to cut them has never been told (in addition to scenes of Rhett Butler’s suicidal ideation with a gun, and even a cross-dressing rioter). If not for Selznick’s choices to err on the side of white pacification, he could have altered the course of one of the most celebrated — and disgraced — movies ever made.

Gone With the Wind is one of the most widely seen and controversial movies in the American canon, the most financially successful production of all time in the United States, and a central pillar in the edifice of the Hollywood studio system. It would win eight Oscars in 1940, including one for Hattie McDaniel, the first African American to earn a competitive Academy Award (though infamously, she was seated apart from her white co-stars at the ceremony).

Undeniably, the movie represented historic achievements in storytelling, color cinematography, production design, acting, orchestration, multidimensional portrayals of female characters, costuming, and efforts to fight the censorship of the Hays Code. But it is equally true that the film had a destructive global influence on the entire world’s understanding of race relations. A French critic once hailed Gone With the Wind as “the Sistine Chapel of Movies,” while director John Ridley more recently summarized it as “a film that, when it is not ignoring the horrors of slavery, pauses only to perpetuate some of the most painful stereotypes of people of color.”

As seen through the lens of lost scenes in a rediscovered script, it also is a stark reminder of the debates and discussions that continue to haunt American culture more than 80 years later.

The Lost Scenes

I discovered this untold history of Gone With the Wind after I stumbled on an antique shooting script for sale at an online bookstore three years ago. I knew immediately the screenplay was an amazing find since, according to the auction at which it originally sold, Selznick had ordered all shooting scripts destroyed. This was one of the last surviving “Rainbow Scripts”, named for the multi-color pages inserted to reflect the famously obsessive producer’s revisions, which continued to pour in even until the final days of the production. I saw that the 301-page script was authenticated for the previous owner by Bonhams, one of the most prestigious auction houses in the world, so I bought it (for $15,000 — don’t ask. More on my GWTW obsessions here).

When I started reading the Rainbow Script, I found it even more incredible than I could have imagined. It was full of lost scenes cut from the movie between February 27, 1939, when the first inserts were added, and some time after June 25, 1939, when the last of them were dated. Some of these scenes were known to me by legend and research, but most of them were never described anywhere else before.

On-set photographs depict some of these lost scenes, confirming that several of them were actually shot. If this material were ever exhibited, it would have been in Riverside, Calif., on Sept. 9, 1939, when Selznick tested the unfinished film in front of a rapturous audience after literally locking them into the Fox Theater and unexpectedly commandeering a double showing of Hawaiian Nights and Beau Geste.

Even more interesting, as I researched the history of the script and the evolution of the movie, it became apparent to me that Gone With the Wind’s inaccurate, romanticized depiction of slavery, which has become a central legacy of the famous movie, had in fact loomed over the production from beginning to end, prevailing over many of the excised scenes in the Rainbow Script.

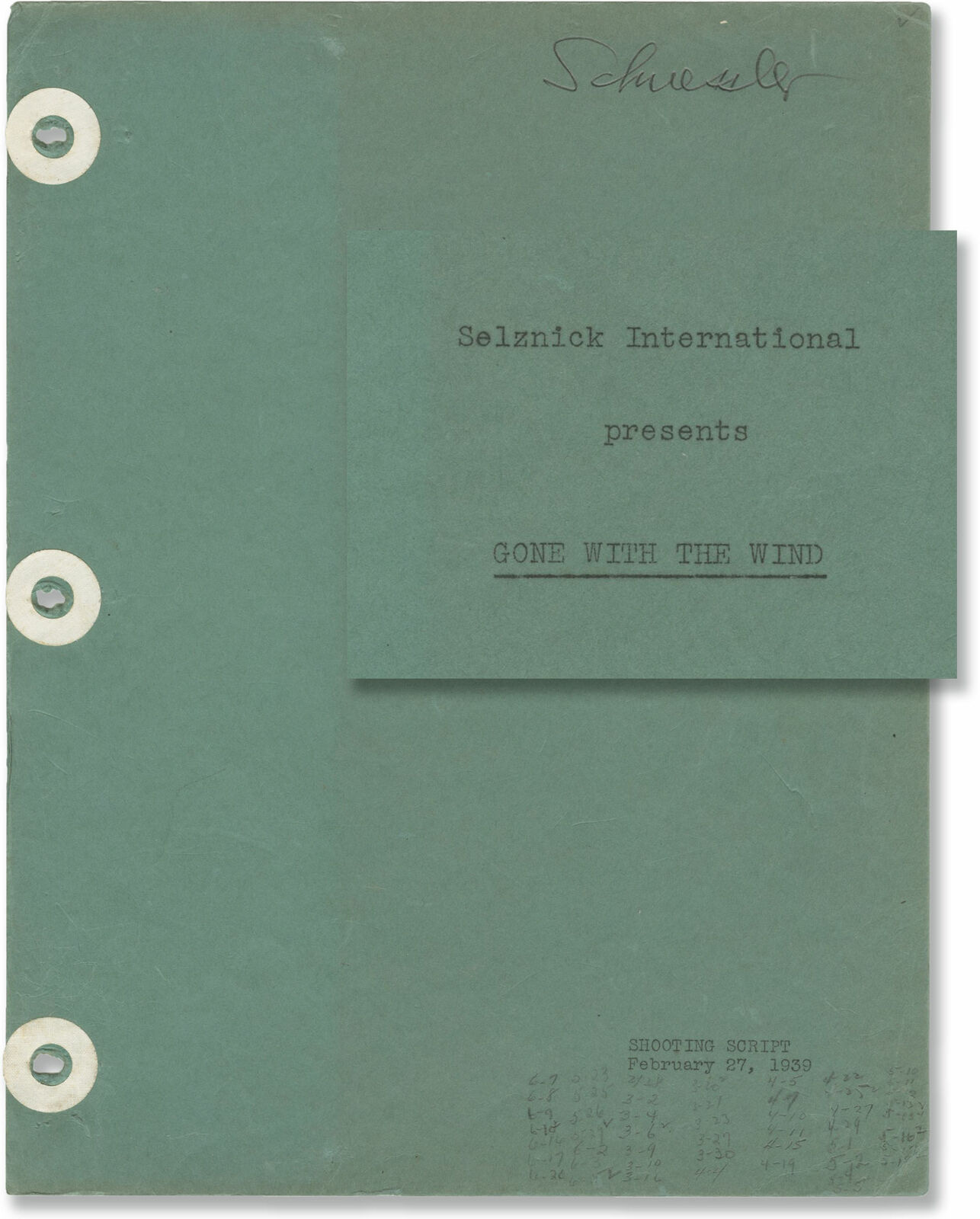

Horrors of Slavery, Deleted

The shooting script I bought had belonged to a seasoned casting director named Fred Schuessler who, for some unknown reason, had defied Selznick’s attempts to destroy it. Of the vanishingly small number of surviving Rainbow Scripts (I estimate there are fewer than half a dozen), every specimen is a little different. One sold at Sotheby’s that belonged to a script clerk, for instance, contains the not-so-immortal line “Frankly, my dear, I don’t care.” According to Steve Wilson at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, the repository of an immense collection of documents related to the Selznick studio, “it would have been the responsibility of each person to keep their script up to date with additions, changes, etc. People in different departments would have different needs and responsibilities so I wouldn’t be surprised if their individual scripts would differ.”

My particular specimen contained evidence of behind-the-scenes drama I’d never imagined, hinting at one of the most important reasons Selznick had fired (and occasionally rehired) over a dozen writers on his film and constantly revised the script himself while feasting, in the words of scholar Alva Johnston, on “a daily ration of Benzedrine and six or eight grains of thyroid extract — enough to send a man to heaven.” The content of Selznick’s obsessive memos tells one story, accentuating issues like poor dialogue and pacing. But the evidence of the lines and scenes actually being added and deleted tell a deeper, more controversial one. After sifting through a mountain of evidence, I discovered that Schuessler’s Rainbow Script was a mosaic that actually represented the perspectives of numerous screenwriters, many of whom held contradictory perspectives on slavery emblematic of the contemporary debate of that day.

Remarkably, much of the excised material in my Rainbow Script was a harsh portrayal of the mistreatment of the enslaved workers on Scarlett's plantation, including references to beatings, threats to throw “Mammy” out of the plantation for not working hard enough, and other depictions of physical and emotional violence. Had these scenes remained in the final film, they would have stood in startling juxtaposition to the pageantry on display at the premiere in Atlanta. At the time of production, GWTW’s romanticization of slavery led African American thinkers like Ben Davis to call it “dangerous poison covered with sugar.” William L. Patterson went even further, describing it as “a weapon of terror against black America.” These voices were in the critical minority in the twentieth century, but over time, scholars have increasingly emphasized GWTW’s promulgation of the mythology of the Lost Cause, an interpretation of the Civil War that romanticizes the struggle as a war of Northern aggression that desecrated Southern honor and culture.

What are we to make of the excised scenes showcasing a very different, brutal view of slavery? Who was responsible for these depictions? Why were they cut? And what price did Selznick pay for his choices?

Realizing that the screenplay of Gone with the Wind had gone through multiple transformations at the hands of more than a dozen different writers and editors, I dove into the archives at the Harry Ransom Center to untangle these mysteries. I was astounded by the sheer breadth of material. I found exhaustive character studies that provided the kind of background information about the enslaved characters that film historians like Donald Bogle have pointed out is sorely lacking in the final production; for example, in answer to his rhetorical question about where Mammy slept, the Ransom archives explain that in her youth, she was “raised in Ole Miss’ bedroom, sleeping at a pallet on the foot of the bed.”

Some of the behind-the-scenes material is excruciating to read. Charged with absolute fidelity to Mitchell’s novel, dehumanizing language trickled from her pages into the words of the creative team itself. Mitchell described a Black assailant as “a squat black negro with shoulders and chest like a gorilla.” A script supervisor mechanically parroted the language in her summary of the movie’s cast, naming the character “Gorilla Negro.” When Selznick expressed his hope to retain the use of the n-word in the script by “the better negroes” and asked his assistant and publicist Val Lewton to seek the counsel of “some local Negro leaders on the subject,” Lewton horrifyingly replied that “the n***s resent being called ‘n***s.’”

Thankfully, there were also voices on set calling for a more historically accurate depiction of slavery. Material from the Ransom archives reveals that Selznick was torn by protests from critics as varied as the Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. Concerned by objections to the film by many in the Black press, he was also in extensive correspondence with Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP. As has been reported, he wrote that as a Jew in a time of rising anti-Semitism, “I, for one, have no desire to produce any anti-Negro film,” and he wanted his team “to be awfully careful that the Negroes come out decidedly on the right side of the ledger.”

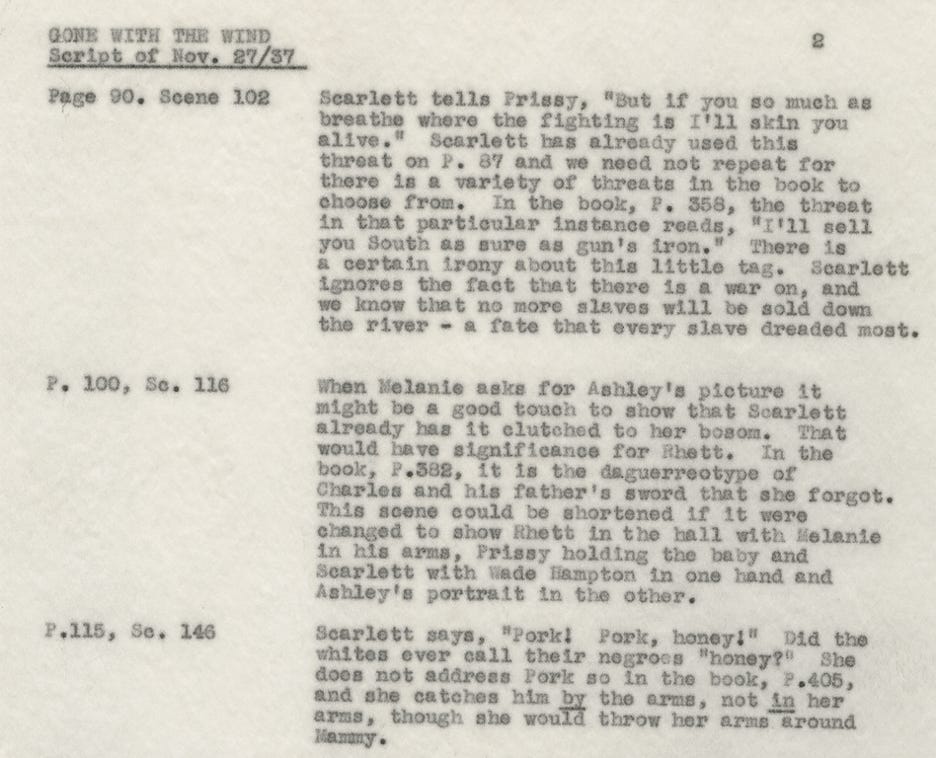

In fact, Selznick was wrestling with whether to include harsh material showcasing the mistreatment of the enslaved. A comparison of different versions of the script from Ransom, which has dozens of earlier iterations, indicates that a behind-the-scenes struggle was central to the arduous process which famously saw the screenplay overhauled again and again until the very end of the production. One member of Selznick’s team even agonized over questions like whether Scarlett should repeat her vow to skin the enslaved Prissy alive or vary it with a threat to sell her South, noting that “we need not repeat, for there is a variety of threats in the book to choose from.”

Screenwriters’ War Over Race

Despite its reputation for romanticization, some of the lost scenes showcasing the brutality of slavery were drawn from Mitchell’s novel itself. In a letter about white convict laborers in the book, Mitchell wrote that “if they had been black Scarlett would not have permitted them to be mistreated because she liked colored people and, in common with most of her generation, she would have felt that Negroes had a market value, even after freedom. (Old ideas will hang on).” Despite Mitchell’s note, which is ostensibly humane but actually dehumanizing, the novel has many scenes of mistreatment.

In Mitchell’s novel, we learn that Scarlett prefers to employ white convicts rather than freed Black laborers because when it came to the latter, “if you so much as swear at them, much less hit them a few licks for the good of their souls, the Freedmen's Bureau is down on you like a duck on a June bug." (This quote was retained in an early version of the script.) Because Mitchell employs third person limited narration and presents events through the prism of Scarlett’s perspective, it is not always clear where the character’s perspectives on race end and those of Mitchell begin. The early scenes in the novel tend to rhapsodize poetically about the aesthetics of plantation life, while the chapters exploring the privations of the Civil War and the period directly after it employ harsh realism to showcase the hardening of Scarlett’s character as she struggles to survive. This dynamic resulted in vignettes glossing over the hardships of enslaved workers early in the novel, and incidents of Scarlett mistreating Black characters during and after the Civil War later in the book.

Selznick’s demand of absolute fidelity to Mitchell led to two tonally contradictory perspectives on slavery and its legacy. Rival groups of screenwriters among the many engaged on the script emerged: “Romantics” who leaned into the mythos of Moonlight and Magnolias, and “Realists” who amped up scenes of mistreatment to highlight the brutality of Scarlett’s character and even condemn the institution of slavery itself. Mitchell herself would give no guidance, responding to Selznick’s query about historically appropriate headgear for Mammy by saying “I refuse to go out on a limb over a head-rag,” and providing no advice thereafter. (Despite this reticence, in later years, she donated part of the proceeds from Gone With the Wind to fund the educations of at least 20 Black medical students at Morehouse College.)

In jarring contrast to the Romanticism of the final film are the earlier contributions of the Realists, including original screenwriter Sidney Howard and Oliver H.P. Garrett, one of his first successors. Howard was an intensely private Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright described by Selznick as one of the “best writers for pictures,” “rare in that you don’t have to cook up every situation” for him and “write half (his) dialogue.” Howard’s treatment of the novel would have been six hours long, and he refused to leave his Massachusetts farm to work on a finalized version with Selznick, who maddened his writers with constant demands for re-writes, sometimes before he had even read their original work. In hopes of adjusting the script, Selznick went on to hire Garrett, trusting the project to the former World War I rifleman and newspaper reporter because the producer admired his ability to distill the complex story into coherent chunks.

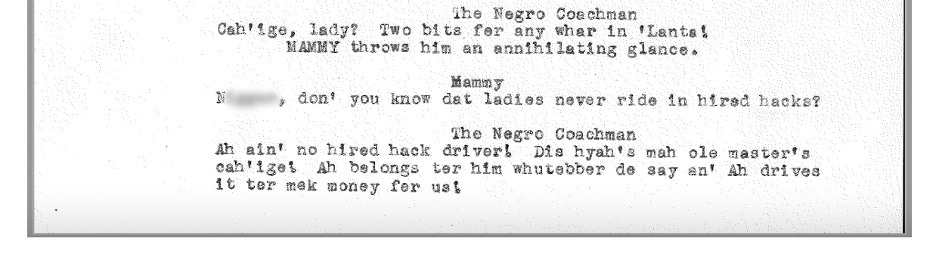

Admittedly, Howard and Garrett were not committed to a complete demonization of slavery. For example, Howard’s version of the script uses the n-word and has a recently liberated coachman declare “Dis hyah’s mah ole master’s cah’ige. Ah belongs ter him whutebber de say.”

At the same time, Garrett’s occasionally clumsy work so dissatisfied Selznick and the crew that it drove the producer to try to rewrite the scenes himself. Sometimes I can understand why. Garrett’s version paused the narrative to include a recitation of the entire Gettysburg Address. And in the climactic scene where Rhett declares that he doesn’t give a damn, Garrett recommended the addition of a valet named Isiah whom Scarlett instructs to spy on Rhett; Rhett and Scarlett’s parting shots are delivered while “ignoring the presence of the Negro.”

Despite an incomplete commitment to a condemnation of slavery by Howard and some incidents of questionable taste by Garrett, their material depicting race relations was so often so gritty and uncompromising that some of it was cut in drafts even before the creation of the Rainbow Script in my possession. Howard and Garrett often took the harshest scenes from Mitchell’s original and made them even crueler.

Howard prefaced his initial script by telling Selznick he wouldn't write scenes caricaturing Reconstruction, refusing to include a planned sequence “which showed how the Yankee crooks were running drays of Negroes about from poll to poll in order to elect a republican government.” He depicts several scenes where the enslaved or recently freed characters are shown luxuriating in the misfortunes of their enslavers, belying the Southern myth that mutual respect was the norm. There is a precedent for this in Mitchell, who wrote “Negroes were always so proud of being the bearers of evil tidings.” But Howard goes further, using this idea as a motif throughout the film. Thus, Prissy “nods happily” at the news that Dr. Meade’s son had been shot in the Civil War; and later, Howard writes that Black characters “enjoyed the drama of disaster.” The scenes were later removed.

Echoes of this treatment remain in the lost scenes of the Rainbow Script. When Pork tells Scarlett that the plantation might have to be sold off for want of tax money, he sings “just a few more days to tote the weary load” and has “mournful enjoyment at the bad news.” His “delighted despair,” and “evident delight” contrast with the plight of Scarlett, so poor that she wears pieces of carpet woven together on her feet. The screenwriter underscores the freed man’s satisfaction at her plight by repeating it three times. The stage directions survive in slightly modified form in the Rainbow Script.

With the exception of Butterfly McQueen’s subversive performance as Prissy, none of these cavalier reactions toward the catastrophes of the white characters is to be found in the final cut. Yet Howard’s original work was so strong that it served as a blueprint for later rewrites, and he even rejoined the production, making further contributions. Crushed to death by a tractor on his farm shortly before the opening, he was honored by Selznick with sole writing credit despite the contributions of over a dozen other hands.

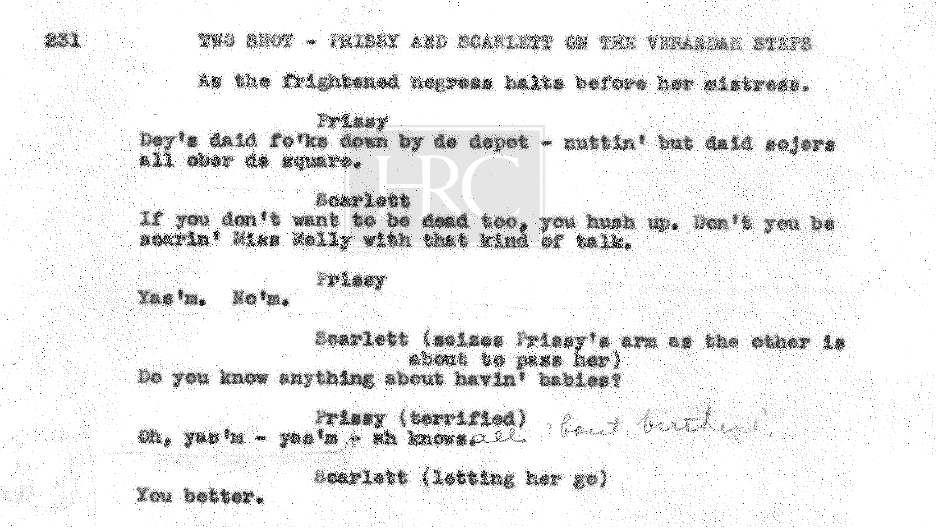

Prissy is the subject of the most graphic depictions of mistreatment in the lost scenes, particularly in Garrett’s version of the script. In the final version of the film, Prissy exaggerates her skills as a midwife due to her own subversive inclinations, just like in the novel. But in Garrett’s version, Prissy lies because Scarlett intimidates her. “Do you know anything about havin’ babies?” Scarlett asks Prissy weeks before Melanie is to give birth, seizing her arm and threatening to strike her. Prissy is “terrified” when she responds “Oh, yas’m - yas’m – ah knows.” “You better” threatens Scarlett.

In another scene with no precedent in the novel, Garrett describes how “Scarlett deliberately raises her switch and brings it down upon Prissy’s back,” screaming “Sit up, you fool, before I wear this out on you!”

Mitchell gives Scarlett the line “I’ll sell you (Prissy) down the river. You’ll never see your mother again or anybody you know and I’ll sell you for a field hand too.” The line appears with slight variations in both Howard and Garrett’s versions of the script. Mitchell had earlier specified that despite the prevalence of many threats toward Black workers at Tara, the O’Haras did not act on them. But no such assurance appears in Garrett’s screenplay. Selznick toned down this content considerably by the time the components of the Rainbow Script were issued, besides a deleted scene in which Prissy is pinched and told to “shut up.” Yet vignettes remain even in the final film of Scarlett threatening to sell Prissy South and “whip the hide off” of her, and she slaps her servant across the face, a remnant of the harshness of these early treatments.

Even Mammy, a character considered like a second mother by Scarlett, is subject to mistreatment in the Rainbow Script, part of the legacy of the Realists that never made it in. Scarlett curses her aged nurse and Pork when they express regret over having to engage in hard labor in the difficult days after the Civil War. In the novel, Scarlett says “anyone at Tara who won’t work can go hunt up the Yankees.” Every early iteration of the script includes this vignette with varying degrees of harshness, but Howard’s version is particularly brutal, with Scarlett saying “I don’t know and I don’t care!” in response to the question of where the formerly enslaved workers should go; in fact, it is a striking parallel to Rhett Butler’s future parting shot.

In the final movie, Scarlett’s father alludes to her harsh treatment of Mammy and Pork, but it is never shown. In a later scene in the Rainbow Script, Scarlett is so distracted by her romantic misadventures that she dismisses her daughter Bonnie from her side, saying “Run along, I’m busy.” Bonnie bumps into Mammy as she leaves. “What are you doing? That ain’t no way for a lady to act,” reprimands Mammy. “You run along Mammy, I’m busy,” answers Bonnie, echoing her mother’s haughtiness. “Mammy gives a takum” in response. (God knows what a “takum” is, but I imagine it might be one of McDaniel’s patented glares.)

Among contributors to the Romantic camp hired after the ousting of Howard and Garrett were F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ben Hecht. Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby might now be recognized as a high watermark in American literature, but he had fallen far in the 14 years since his literary triumph, struggling against the bitter disillusionment of professional failure and alcoholism while working to modify Garrett’s script. His work as a screenwriter and script editor inspired director Billy Wilder to call him “a great sculptor… hired to do a plumbing job. He did not know how to connect the pipes so the water could flow.” Selznick warned Fitzgerald to limit his creativity; the author complained that “I was absolutely forbidden to use any words except those of Margaret Mitchell; that is, when new phrases had to be invented, one had to thumb through as if it were Scripture and check out phrases of hers which would cover the situation!” As for the book itself, after a litany of complaints about it, he admitted that he considered it “interesting, surprisingly honest, consistent and workmanlike throughout, and I felt no contempt for it but only a certain pity for those who consider it the supreme achievement of the human mind.”

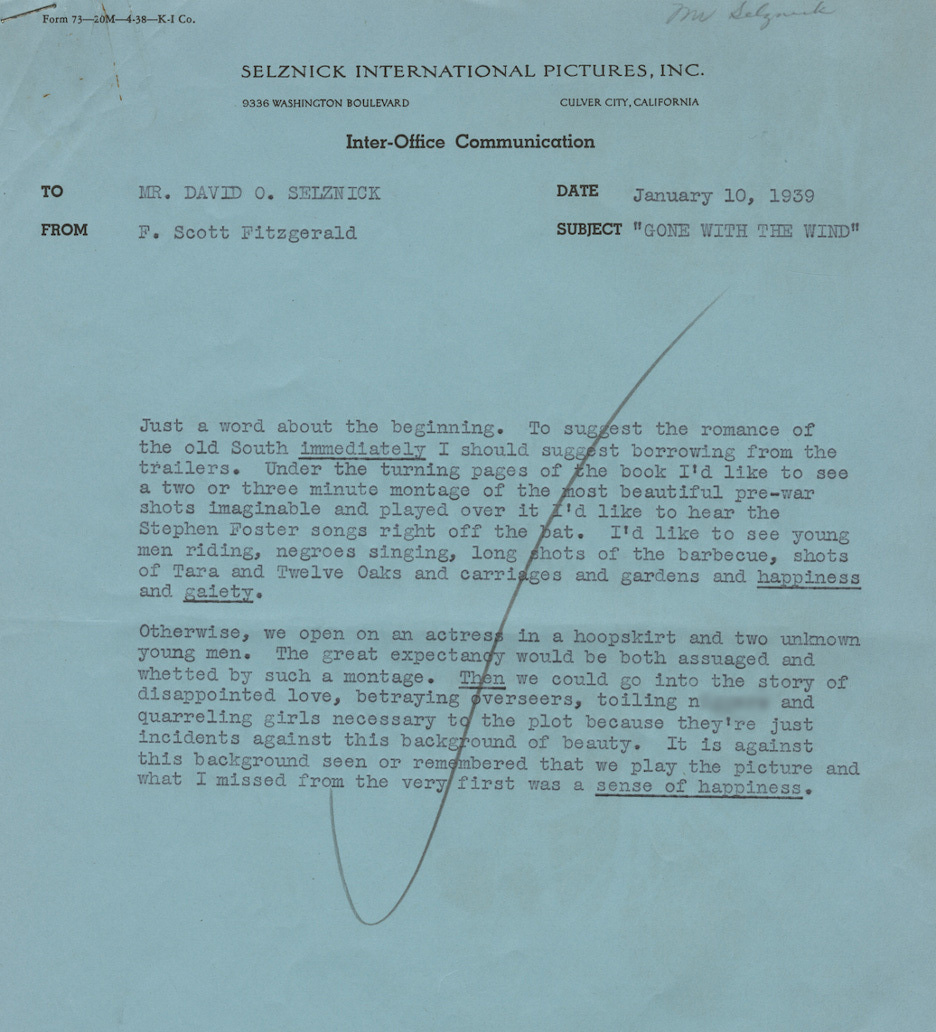

Unfortunately, Fitzgerald’s perspective on antebellum slavery was utterly regressive. For example, he employed the n-word in a note to Selznick, “To suggest the romance of the old South immediately… I’d like to see a two or three minute montage of the most beautiful pre-war shots imaginable… I’d like to see… negroes singing… Then we could go into the story of disappointed love, betraying overseers, toiling n*** and quarreling girls.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald Fired

While Fitzgerald’s contributions to the final film are often described as marginal, the kind of nostalgic tone he recommended actually permeates the beginning of the movie with its dramatic credits projected over images of a romanticized South. But before Fitzgerald could have further influence, he was unceremoniously fired from the production for failing to make Scarlett’s Aunt Pittypat sufficiently funny; she was supposed to “bustle quaintly around the room,” but after hours of frantic discussion about what on earth this meant and his failure to conjure up a good way to convey it on the screen, Fitzgerald was informed of his unemployment by telegraph. A year later, he was dead.

Ben Hecht, who was called “the Hollywood screenwriter” and a man who “personified Hollywood itself” by author Richard Corliss, had a more pervasive influence. The gruff, chain-smoking scribe who worked on more than 70 screenplays, from Wuthering Heights to Hitchcock’s Spellbound to Casino Royale, was hired to overhaul the screenplay with Selznick and Victor Fleming after the latter left The Wizard of Oz to serve as GWTW’s new director.

Fleming’s predecessor, George Cukor, had been fired for his allegedly glacial pace and reputation for favoring the film’s female stars over Gable. Fleming, by contrast, was Gable’s close friend. A superb craftsman of epic crowd-scenes, he was also a hard-nosed bully who once slapped Judy Garland across the face for failing to be sufficiently serious on the set of Wizard of Oz. He would prove to be Vivien Leigh’s nemesis, storming off the production of GWTW for a time after telling her to stick the script up her “royal British ass” following her critiques of it. But he too had problems with the screenplay.

As soon as he took the job, Fleming bluntly told Selznick, “you haven’t got a fucking script.” Hecht was hired to join Fleming and Selznick for a frantic re-write evidently fueled by a forced diet of Benzedrine, salted peanuts, and bananas gobbled down on Selznick’s orders. Hecht insisted they toss Garrett’s work and return to Howard’s blueprint. Nonetheless, he largely sanitized the original writer’s depiction of slavery.

Hecht was ultimately responsible for the film’s opening titles which called the Old South a land of “Cavaliers and Cotton Fields” where “Gallantry took its last bow,” prompting even Margaret Mitchell to cringe (“I certainly had no intention of writing about cavaliers,” she sniffed). Hecht may also be the author of intertitles in the Rainbow Script comparing the Union Army’s General Sherman to “Attila the Hun”, inaccurately calling his march through Georgia “one of the most brutal assaults history has ever known.”

It is tempting to credit other lost scenes in the Rainbow Script to Hecht since they strike the same thematic tone and only appear in material dated to after he came on as a screenwriter. But because the differently colored inserts likely reflect the contributions of diverse authors, we cannot be sure. There is a scene where a Black boy reads a casualty list to his fellow workers after the Battle of Gettysburg (ignoring the fact that literacy among the enslaved was illegal in Georgia) and they “break out into lamentations” over the death of their enslaver.

In the same vignette, a cut character called Grandma Tarleton is so overcome with emotion that she hands the casualty list to her enslaved driver, and he is the one who reads the news about her dead grandsons to her. Photos of the filming confirm that this scene was shot, and it is based on no precedent in the novel.

Another late addition to the script bridging the Romantic and Realist camps depicts the Northern-born overseer Jonas Wilkerson in a harsh light, contrasting the gentility of the Southern characters with his viciousness (including content also without parallel in the novel). When a field hand tells him “I plowed more than yesterday,” Jonas responds, “I want more than that tomorrow.” After the Civil War, he is encouraged by a free Black man named Bill to deliberately trample a Confederate soldier with their carriage: “Ride ‘em down, boss!” Bill cries. The soldier complains about his right to be on the road. “You and your rights!” scoffs Jonas. “You ain’t whipping slaves and kicking loyal Americans down anymore! Shoot ’em down, Bill, if they answer back.” While these scenes suggest the brutality of the overseer and even include references to alleged whippings, the audience is left with the impression that the accusations are unreliably over-the-top, and that if anyone was cruel to field workers, it was Jonas himself. By contrast, the Confederate soldier seems quiet, dignified, and utterly sympathetic. A version of this scene playing down the violent language was included in the final film.

In another cut sequence, a Northern woman accidentally bumps into Mammy on the street and cleans her arm where they had touched, underscoring the idea that the Yankees rather than the Southerners are the true locus of racism. Along similar lines, in a scene drawn from Mitchell’s original which Selznick very much wanted to put in the screenplay though he never dared to include it, the character Uncle Peter was to have a heartfelt monologue about his sorrow over being called the n-word by rude Northerners.

The question of why the harsh treatment of slavery was axed is complex, and a fair answer demands a look at wider changes between the Rainbow Script and the final film. While scenes showcasing the brutality of slavery were among the most prevalent and eye-catching cuts, the necessity of trimming down the eventually four-hour film led to a litany of other deletions, many of which had nothing to do with slavery. In contrast to the idea that Selznick was envisioning his movie as pure Confederate propaganda, he actually omitted several montage sequences in the Rainbow Script glorifying the Southern army. The film would have begun with an image of Fort Sumter with the Confederate flag being hoisted above it, and a scene was later planned showing Pickett’s Charge with capitalized intertitles saying THE GHOSTS OF THERMOPYLAE AND BALACLAVA LOOKED DOWN UPON THE MATCHLESS INFANTRY OF THE SOUTH. A montage juxtaposed Southern military victories with scenes of economic privation and sacrifice.

Omitting this historical material might have arguably helped to focus the film on the human story at its core. But unfortunately, moving scenes were also excised, like Scarlett comforting a dying soldier desperate for human touch by putting her hand on his cheek, before another prisoner coarsens the mood by expressing gratitude that the death of the ailing man will finally bring him peace and quiet. Later, a Protestant minister and Catholic priest comfort each other after the Battle of Gettysburg beside a woman sobbing over her setter dog. Other, more heavy-handed touches also ended up on the cutting room floor:

Hooligans carrying off pig carcasses at the burning of the Atlanta depot, producing silhouettes with “a weird effect of half human half animal figures”

In that same surreal scene, a man wearing a woman’s bonnet and raiding dresses from a clothing store, with gowns overflowing in his arms.

A flashback of Rhett and Scarlett’s relationship before their final scene together.

Rather than “After all, tomorrow is another day,” the final line “Rhett! Rhett! You’ll come back! You’ll come back! I KNOW you will!”

Comedic scenes were also omitted:

A young Scarlett belches and is called a pig by her sister before they descend into a slap-fight.

When Scarlett marries Charles Hamilton to spite Ashley Wilkes, the object of her unrequited love, Charles suggests that “we’ll have a double wedding with Ashley,” to which Scarlett sharply replies “We will not!”

There is also a section written for laughs where maids and sex workers offer testimony in court to provide a false alibi for a raid. One of the women says, “Of course we were drinking. What do you take me for, your honor?”

Far from only focusing on slavery, much of the cut material in the Rainbow Script also fleshed out characters like Clark Gable’s Rhett Butler. When Rhett sees Scarlett at the barbeque for the first time, he is told she is “the hardest-hearted girl in the state of Georgia.” Asked if he’d like to meet her, he replies, “No, I’d rather watch her.” When Scarlett says of the South “I never dreamed it would end like this,” he says, “I did. I always saw these flames.” After Scarlett miscarries, he blames himself for her plight and is only dissuaded from shooting himself by a conversation with Melanie. In the final film, an echo of this somber turn in the story survives; Mammy tells Melanie that she feared Rhett was suicidal after the death of Bonnie. The cut scene in the Rainbow Script dramatizes Rhett’s thoughts of suicide and confirms Mammy’s suspicions in an earlier context.

In other lost scenes, the birth of Rhett’s daughter Bonnie brings out hidden depths of tenderness. When Bonnie cannot fall asleep, she holds his finger in her small hand, and he cancels his plans for the night rather than disturb her. Later, when Bonnie complains about mother Scarlett’s absence during a riding lesson, Rhett says, “You want her to have fun too, don’t you?” And Bonnie replies, “Well, doesn’t she have enough fun with me?” The scene motivates the child’s desire to prove her prowess at jumping over fences on her pony to her mother, adding further tragedy to the character’s death.

Were the deletions of harsh scenes of slavery simply in line with these other edits? Or did Selznick lean into material sugarcoating slavery and edit out many of the harshest scenes under pressure to make the protagonists sympathetic to white audiences, especially in the South? Regardless of his motive, as a result of his decision, from a modern perspective still struggling with the idealization of the antebellum world, the producer created a kind of cinematic Confederate monument whose critical reputation was increasingly called into question. It is a classic with an asterisk, a work that is separate and not exactly equal in the eyes of many commentators, to take an apt metaphor from the work of scholar Claudia Roth Pierpont.

The Premiere’s Own Compromises

The Ebenezer Baptist Church choir, which included Martin Luther King Jr., had been hired to sing in front of the garish, painted backdrop of a plantation. King’s father agreed to organize the repertoire, despite a committee of concerned parishioners urgently dissuading him from having anything to do with the premiere. Perhaps the pastor hoped that the performance might build bridges in a segregated city that was preparing for an event ecstatically welcomed by many in the white community. A massive crowd of 18,000 people swarmed around the segregated theater to catch a glimpse of the action.

Gable was all smiles that evening, but then again, he was a consummate actor. The truth was that the star had threatened to boycott the premiere over the same kinds of racial concerns that had animated Black opponents of the Baptist Choir’s performance. Gable had been an ally to his co-stars of color on set, threatening to quit the production if its bathrooms weren’t desegregated, successfully changing the situation. Now, he was livid that his friend and co-star McDaniel had been banned from the segregated premiere, with organizers even excising her face from the program. Selznick hadn’t intended for this to happen — he’d actually planned for his Black actors to advertise the movie in Atlanta’s neighborhoods of color, but local organizers vetoed the idea. They envisioned a celebration where Black participants would appear, in the words of historian Taulby Edmondson, “as either subservient, fictional slaves, or not at all.” In the end, history’s most notoriously uncompromising producer compromised. Gable attended the premiere only after McDaniel told him that the success of the movie meant more to her than his show of solidarity.

To call the four-hour epic a success is an understatement. Londoners braved the Blitz to see it, inspiring Churchill to say that he was “pulverised by the strength of [its characters’] feelings.” The film was banned in Nazi Germany for its uncompromising depiction of the horrors of warfare, and some reportedly risked death to smuggle the book into concentration camps, a phenomenon echoed half a century later when a tattered copy was secreted into an Ethiopian jail and translated into Amharic to inspire political prisoners to survive and resist.

Unfortunately, the movie also garnered praise from the world’s greatest megalomaniacs. Despite the Nazi ban, Eva Braun obsessed over it. Goebbels promised to “follow [the movie’s] example” in German film, and he called Leslie Howard, who starred as Ashley Wilkes, “Britain's most dangerous propagandist”; the Luftwaffe deliberately shot down a plane carrying the actor, killing him in 1943. Hitler also offered a large reward for the capture of Gable, who flew five combat missions, including one over Germany in which his plane came under fire. Madame Mao repeatedly expressed her admiration for the movie while organizing the Cultural Revolution, holding screenings for top members of the CCP and using it as a reference for Chinese propaganda films despite its idolization of aristocratic landowners. Much later, Donald Trump lamented the 2020 victory of the Korean film Parasite at the Oscars by wishing that movies like Gone With the Wind were still being made. All of this is to say that while it is hotly debated whether Gone With the Wind is one of the greatest films in world history, it is one of the few that is unquestionably a part of the history of the world itself.

The Legacy

Selznick fought hard for McDaniel’s Best Supporting Actress Oscar, partly due to his great respect for her performance, and partly as a strategy to diffuse negative reactions to GWTW in the Black press, which he increasingly attempted to court even after the movie premiered. After calling in a favor for her inclusion in the Oscar ceremonies, he was dissatisfied when she was seated at the back of the room and had her seat moved to a more prominent location, though not at his table, still set apart from her co-stars.

After she won the Academy Award, McDaniel donated her plaque (winners of supporting actor Oscars weren’t given gold statues until 1943) to Howard University, which displayed it in their fine arts building. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, it disappeared. According to Denise Randle, who was in charge of cataloging Howard’s artifacts, it could have been thrown away by protestors who resented the role of Mammy. “At that time,” Randle explained, “it was ‘Black Power, Black Power,’ but they may not have understood where she really stood in the film industry and the pioneer that she was.” Later, Randle suggested that since it was a plaque rather than a statue, people may have been looking for the wrong thing, and it may have been hidden or forgotten. There is a legend that it was thrown into the Potomac around the time of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

While it is debatable whether Selznick cut scenes to romanticize the antebellum South, there is also another possibility. Could the deletions be related to the producer’s concerns over Black responses to GWTW? According to the pioneering work of historian Taulby Edmondson, one could argue that Black resistance to GWTW was ironically crucial to its ultimate longevity as a cultural artifact, since the elimination of the n-word and overt references to the Klan put the work into a different category than the more overtly racist Birth of a Nation, a film that Selznick refused to remake (even though he wrote years later in 1941, “on second thought, this isn’t a bad idea!”). Perhaps the producer feared that like the naming of the KKK, the inclusion of harsh material without explicit negative commentary condemning it might have seemed to be condoning it, especially in the company of the more romanticized content which the film clearly celebrates.

Then again, it might be a mistake to give Selznick any benefit of the doubt. According to Hattie McDaniel biographer Carlton Jackson, Louise Beavers auditioned for the role of Mammy wearing “her finest clothes,” but “Hattie showed up authentically dressed as a typical Old Southern Mammy. The producer was so impressed, he said he could ‘smell the magnolias.’” On the subject of slavery, it seems, David O. Selznick’s heart was with the Romantics. Wearing her rags, Hattie McDaniel’s heart was probably with her parents, born slaves. But she said that she’d rather “play a maid and make $700 a week than be one for $7.”

The author expresses his deepest thanks to the team at the Harry Ransom Center, Mark Mayes, Francesca Miller, and Javi Mulero for their invaluable help and advice.

Very interesting scholarship. A real contribution. Good enough to make me subscribe.

I wasn't surprised at the really awful level of actual writing in the various scenes. The comment about a scene being hard to figure out how to do from the writing got a laugh here, from a screenwriter who has spent half my years in Duh Biz as the "rewriter" the people with their names in the credits hate because they know the movie's success is due more to that work than theirs; I'd say in half the jobs I've done, simply rewriting in understandable standard English was the main improvement I made that set the project on the road to ultimate success. And this SF State grad always gets a kick out of the fact that the really bad ones are always "Ivy Leaguers."