Female Execs' Awful Truth

Not a single woman leads an entertainment conglomerate in the S&P 500. What's wrong at our companies and how to fix it

Lacey Leone McLaughlin is president of LLM Consulting Group, Inc. Coaching leaders across all industries, she specializes in teaching leadership and management skills to creative talent within entertainment, and has worked across studios and production companies. She is also host of the podcast UNFOLDING LEADERSHIP.

Here’s a recent tale from corporate America, as reported in the Wall Street Journal. An executive worked at a company for 27 years. They climbed the corporate ladder. Across the board, their teams spoke highly of them and even called them inspiring and motivational. The numbers matched employee feedback: The executive transformed their division into a $27 billion juggernaut. Naturally, reporters asked the leader what was next, and they even told Fortune they would consider a CEO role. This leader was praised for their success and ambition, right? Wrong. She left the company, and the public perceived that she was penalized for wanting the CEO job.

This is the story of Johnson & Johnson executive Ashley McEvoy as told by the Journal’s Peter Loftus. Early this year, McEvoy left the company after building its industry-dominant medical device unit.

After reading the story, and considering many like it from over the years, I was left wondering how this keeps happening. Why do we still fall short with talented female leaders? Upon reflection of my many years working with both male and female leaders, I believe it comes down to four missed opportunities:

1.) Mentorship

2.) Giving women the space to ask for what they want and deserve

3.) Sponsorship

4.) Letting women own their success

Hollywood may hear this story and dismiss it as a big pharma or a Wall Street phenomenon. After all, we’d like to consider entertainment and media an overwhelmingly progressive industry. We care about gender inequality. But as an executive and leadership coach working in the entertainment sector, am I surprised by the outcome described in the Journal?

Leaders — both male and female — I’ve worked with have experienced similar situations, and there are ways we can flip the script.

Mentorship Could Fix Bad Numbers

It’s easy to outweigh our experiences or overheard anecdotes in these complicated times. So, I like to review the data to see what is happening in American businesses. I turned to the numbers about women CEOs and board members, which reveal we can do things differently.

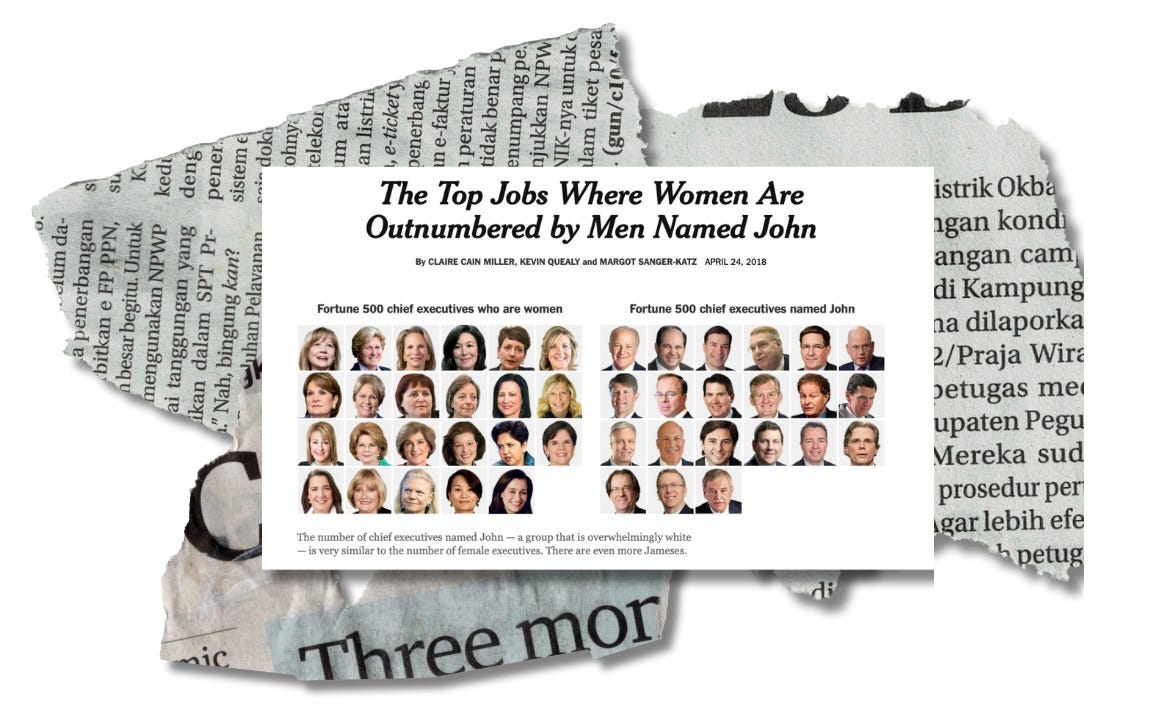

How bad is the state of women CEOs? Last year was the first year there were more female CEOs than CEOs named John. According to the New York Times, Johns made up to 3.27 percent of the American population, while women made up more than 50 percent in 2018; yet the “Johns” of the world making up only 3.27 of the population were represented in the top seat more often than a group of people that make up of 50 percent of the population. This news was apparently such a milestone that Axios, Bloomberg, and more devoted whole stories to it.

How could we improve these numbers, so women CEOs could give men named John (just the Johns!) a run for their money? The answer goes back to conversations I’ve had with leaders I work with. When I’ve asked leaders at the top of the industry about their successes, it always comes back to one or two people professionally that “believed in me,” “took a chance on me,” and/or “invested their time in me.” This is mentoring.

Countless studies attribute the impact of mentoring on promotion, job satisfaction, stretch assignments, confidence, opportunity, and mental health. But a DDI study found that 63 percent of women have never been mentored. This negatively impacts women because mentees are promoted five times more often than those without mentors.

A recent Wall Street Journal article examined the impact of networking for women and men. It found, “When women built networks with high-status contacts, instead of receiving a status boost, their status gradually declined over time. Such a costly effect didn’t occur in men.” Consistent with the Johnson & Johnson article, women are impacted differently than men for their perceived ambition.

More leaders need to step up and mentor the women working in their teams. All leaders — both men and woman — need to recognize and reward woman who find powerful mentors and build a strong network of support. We need to move past our biases and celebrate women’s ambition rather than finding it intimidating and “off-putting.”

‘Take It Or Leave It’

If a woman has a mentor, she still needs the space to ask for what she wants and deserves. We’ve made some strides in hiring women CEOs, but pay remains a problem.

The exact numbers of women CEOs differ depending on how you break it down and how you group companies. Fortune found women only led 10.4 percent of Fortune 500 companies in 2023. According to Catalyst, women only made up 8.2 percent of women CEOs in the S&P 500. Yet as the number of women CEOs has risen, their pay has dropped. The AP reported in 2022 their median pay packages fell 6 percent. In contrast, male CEOs’ pay bumped up by one percent.

These numbers match my experience. Problems occur before HR even onboards the new leader. We all know how negotiating should work. After interviewing, the company sends their choice an offer, and the prospective candidate responds with a counteroffer. The company and the candidate go back and forth till they reach an agreement. But that isn’t always the case with women I’ve coached and been along for the ride as they negotiated their packages. These leaders could not ask for what they wanted in the same way I’ve seen their male counterparts. Several times, I’ve coached a female executive, and the response to her counteroffer is a flat “take it or leave it.” In one case, a female CEO received a salary offer of a third of her male predecessor’s pay.

Not a single male client has received a take-it-or-leave-it response. Women CEOs end up with no choice but to take it or leave it — and this sets a precedent for them being undervalued and accustomed to being treated differently than their male peers. Boards need to consider how they handle women executives’ negotiations and ensure they’re treating them the same as male CEOs.

Of course, this change wouldn’t impact women CEOs in Hollywood, though. Not a single woman leads a Hollywood entertainment conglomerate in the S&P 500. (In music, it’s worth noting Sherry Lansing is chair of the board of Universal Music Group.)

Why Having Women on the Board Matters

Boards pick CEOs, and CEOs report to the board. Boards’ makeup matters in who gets to lead. Right now, the number of women board members doesn't reflect how many women are in the U.S. population.

Like with CEOs, the numbers depend on the index or company groupings. MSCI found that less than one third of companies have women on boards. The Conference Board, a think tank, found the percentage of female directors “increased from 23% in 2018 to 32% percent in 2023,” among S&P 500 companies. But the increase was a decrease of a percentage point from a year earlier.

Diversity is slowing down after regulators tried to ensure gender equality on boards. California attempted to mandate women on boards, but a California judge struck down the law last year. Since California overturned the bill, Forbes reported the numbers have worsened, citing “the proportion of women on boards fell to 32.75%” by September 2023.

The numbers are better in other groupings, though. Among Fortune 500 companies, Forbes reported women only held 44.7 percent of seats.

The numbers are worse when it comes to board chairs. Fortune analyzed board directors at Russell 3000 companies and discovered that only “only 7% of board chairs and 13% of lead directors are female.”

Among the publicly traded entertainment companies and tech streaming companies, Shari Redstone is the only woman to lead a board — and she notably controls voting share of the stock inherited from her dad.

So what’s the impact of this? If fewer women sit on boards, do fewer boards sponsor women executives for board seats and top leadership spots? Are fewer leaders willing to act on behalf of women when the board lacks women? Sponsors listen and act and are hands-on in providing feedback, seeking out new opportunities, and advocating on their behalf of the person they are sponsoring. Within an organization, more women having sponsors advocating for them could have a huge, lasting impact on succession planning. It would lead to more people asking, “Are we talking about women leaders in the same way we’re talking about their male counterparts? Is there an opportunity for those in the room to change the conversation and engage differently as a sponsor?”

Letting Women Own Their Success

The good news is that there are more women than ever who are in executive positions that could lead to future CEO or board positions. A San Diego State University study found “24% of executive producers working on the top 100 films of 2022” identified as women.

With that, let’s encourage and celebrate women owning their success like men do. Let’s be excited when a woman with a proven track record of success is asked, “Would you want the top spot?” and she says, “Yes.” Let’s hold ourselves accountable to reflect and understand why we might react, take offense, and be intimidated by a woman leader having a voice, being proud of what she’s achieved, and voicing what she wants, and acknowledging she is capable of more.

When we think about adult development, it starts with insight and awareness. We ask leaders to reflect on how you respond/react to a woman's success and ambition? Is it similar or different from her male counterparts? We all need to ask ourselves these questions.

What the Numbers Tell Me, and How We Can Improve

So how do we fix this? First, we need to keep talking about boards, women leadership, and diversity. We need to make sure women are mentored and sponsored the same way as their male counterparts. We need to pay them what they are worth and not be surprised when they ask for it, and we need to celebrate their success and ambition and encourage them to be ambitious. Most of all, we need to normalize that it’s okay for women, like men, to want the big job, say it out loud, and actively go after it.