Documentary Spotlight: Inside the Films Cutting Through Power, Prisons & Patriarchy

Filmmakers on four of the most impactful stories on the Oscar doc shortlist

At AnklerEnjoy, the home for post-Ankler Events content, you can watch all of the documentary panels from our virtual Jan. 7 event (and previous Documentary Spotlight events).

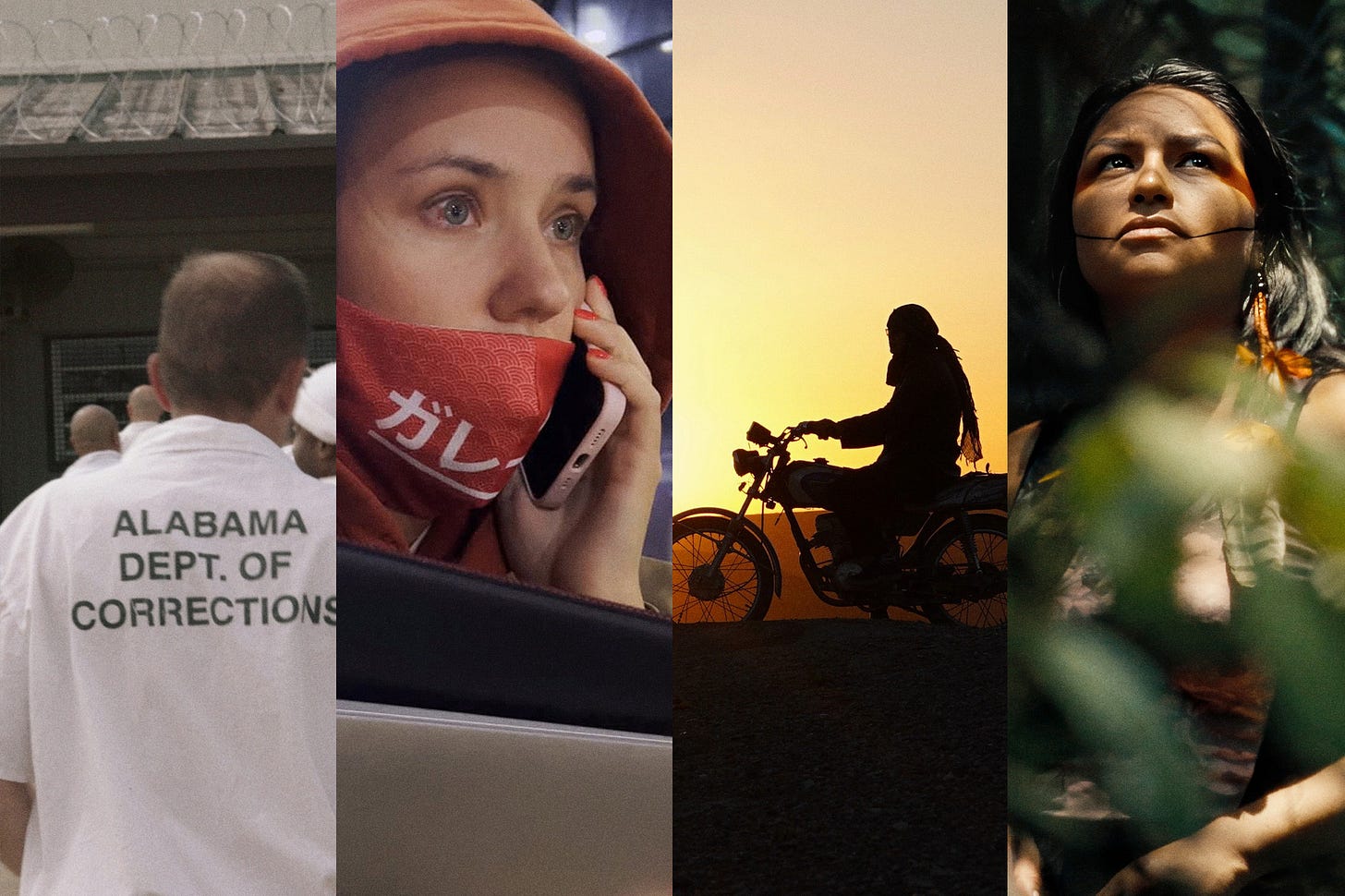

Cutting Through Rocks (Gandom Films)

My Undesirable Friends: Part I — Last Air in Moscow (Marminchilla)

The Alabama Solution (HBO Documentary Films)

Yanuni (Malaika Pictures)

You can also listen to audio of these filmmakers in conversation with Thom Powers here on the Pure Nonfiction podcast. (For information on Thom’s new book, Mondo Documentary, head here.)

In what marked the 10th collaboration between The Ankler and Pure Nonfiction, Powers hosted our latest Documentary Spotlight, a virtual event highlighting The Alabama Solution, My Undesirable Friends: Part I — Last Air in Moscow, Yanuni, and Cutting Through Rocks. The Jan. 7 edition was attended by members of AMPAS, BAFTA and IDA from around the world.

Born and raised in Tehran, Iran, Sara Khaki grew up witnessing women striving for independence in a patriarchal society. When she moved to the United States, Khaki still thought of the women who never left Iran, unlike her.

“What are they doing, and how are they pushing for space for the women and girls around them?” Khaki recalls thinking.

Her answers came in the resulting documentary, Cutting Through Rocks — filmed over seven years with her co-director and eventual husband, Mohammadreza Eyni. The film follows midwife Sara Shahverdi as she runs for a local council seat in her Iranian village, aiming to break long-held patriarchal traditions, like discouraging teenage girls from riding motorcycles.

“It’s such a normal thing now for women to ride motorcycles,” Khaki told Pure Nonfiction’s Thom Powers during a Jan. 7 conversation. “This is one of the many examples of the change and the evolution that happened within this one small part of the planet.”

Khaki and Eyni, along with the filmmakers behind three other Oscar-shortlisted films, joined Powers to share how they managed to take big themes — the Iranian patriarchy, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, cruel American prison conditions and the cost of resistance — and deliver narratives about them with a tight, personal focus.

In the Action: The Alabama Solution; My Undesirable Friends: Part I — Last Air in Moscow

Journalists cannot just speak to people who are incarcerated, explained The Alabama Solution co-director and producer Charlotte Kaufman to Powers. “They cannot visit prisons, historically, unless they have the permission of the state,” she added. “What is very unique about our film is that we are seeing the truth about what incarceration is without the permission of the state.”

To expose the corrupt, cruel conditions present in the Alabama prison system, Kaufman and fellow co-director and producer Andrew Jarecki crafted a documentary using contraband cell phone footage provided by the inmates over several years. It all began in 2019, when the duo visited Easterling Correctional Facility to film a religious revival meeting. Off camera, the incarcerated men — often put away for non-violent crimes — discreetly hinted at stories of the abuse they had endured.

“There is widespread use of unpaid labor within the prison system in Alabama and within prison systems across the country,” Kaufman said. In Alabama, she explained, that means being leased out to different towns and municipalities to do all of their landscaping or even to work in the governor’s mansion. “That alone is hard to accept, but when you combine the violence that exists in the prisons, and you realize what’s at stake if they refuse to work,” she said. “It’s coerced labor at the threat of bodily harm. It takes it to a whole other level.”

Jarecki and Kaufman had “terabytes and terabytes of information,” Jarecki said, from inside the prisons. The challenge then became how to assemble a film about a topic as nuanced and layered as the prison system.

“You have so many elements that you would like to talk about,” Jarecki said. “It’s critical to talk about the slave labor. Without it, you don’t understand what the big economic engine is that’s driving this. But then again, they’re building $3 billion worth of new prisons. Then again, they’re not paroling people.

“Every one of these things could be a film.”

Faced with a similar predicament (too much footage, not enough time), documentarian Julia Loktev opted to turn what was once intended to be a feature-length film into a two-part project (with the potential for a third part). Loktev first traveled to Russia in October 2021 with the goal of documenting independent journalists; then, four months later, Russia invaded Ukraine.

“Everything about the process feels very organic and, obviously, surprising and unexpected,” Loktev told Powers. “When I started making the film, I obviously had no idea that a few months later, all of these characters would be facing the decision of, ‘Do we go to work tomorrow? Do we go to prison? Or do we go to the airport right now with a carry-on suitcase,’ which is a pretty tremendous thing to happen in your life.”

Loktev became a one-person crew with an iPhone, which allowed her to remain inconspicuous while capturing the rapid disintegration of Russia’s civil society. The resulting film, then, became less investigative and more of a “hangout” movie with the journalists as they faced the agonizing decision of whether to abandon their country.

“All the journalists I was filming were expecting a crackdown, and they thought this was going to get worse and worse,” Loktev said. “Everybody thought the monster would eat them, not invade the neighborhood.”

My Undesirable Friends: Part I — Last Air in Moscow concludes in March 2022, and Loktev is currently editing a sequel that follows her subjects, who made the difficult choice to leave Russia and head into exile.

“Part II starts two days later as they’re in Istanbul. They have no idea what country they’re going to. Their bank cards don’t work. They have no media. Their country has just started a war, which they’re incredibly ashamed of and horrified by,” Loktev said. “They feel like they should report on it, but they don’t have any media because all their media has been closed.”

Powerful Women: Yanuni; Cutting Through Rocks

Juma Xipaia, an indigenous chief who rose from Amazonian activism to Brazil’s Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, had survived six assassination attempts when she met documentarian Richard Ladkani. He proposed an out-of-the-box solution: Use a documentary film not only to stay safe but also to bring meaningful change.

“If millions of people know who you are,” Ladkani recalled saying, “you will become a much harder target to take out. There will be outrage, a media storm and questions and answers. I see it as a new tool in your tool set, basically, to fight.”

Ladkani served as director, producer and cinematographer on the resulting film, Yanuni, which counts Leonardo DiCaprio and Xipaia herself as producers. To add to Xipaia’s dangerous circumstances, her husband, Hugo, a federal agent, conducted raids on environmental criminals throughout filming. Ladkani joined Hugo on dangerous operations to capture the Amazon rainforest’s destruction firsthand, using small cameras and no crew to avoid attracting attention. But that wasn’t the only potential danger the documentarian put himself — and his subjects — in.

“Here I was with a camera running around in one of the most dangerous places of the Amazon,” Ladkani said of his travels, “where people get shot and killed every day on the streets.”

To build trust and mitigate security risks, Ladkani spent six months learning Portuguese, eliminating the need for a translator. In the end, all the danger and precautions were worth it.

“The community sees it as their indigenous film that has made it out there to the world to tell their story, and they’re super proud,” Ladkani said. “Juma is super proud because this is her film.”

Likewise, for Cutting Through Rocks filmmakers Khaki and Eyni, doing right by their noble subject and her community was paramount. The challenge became that the moment the duo walked into the village, “there were questions about who we are and what our intentions are,” Khaki recalls.

The two-director approach helped, with Khaki able to access intimate female circles and Eyni allowing men to feel their voices were being heard. Eyni’s fluency in the local dialect also helped. As the duo built up their relationships within the community, profound cultural shifts were underway. Shahverdi asserted herself as a role model in the community, inspiring a new generation of village girls to pursue education — and yes, ride motorcycles.

“For us as filmmakers, it was a lesson to see how change is contagious, to see how it’s possible,” Eyni told Thom Powers. “It seems that it’s impossible, but if you fight for it, you can make it possible.”

Ah, Hollywood making bullshit comments about men, still.

You know this is why theaters are empty and nobody wants to watch this utter divisive garbage.

How many acting women shut their mouths during #metoo after they fucked their way to the near top? Thousands?

Someone needs to make a documentary about that!