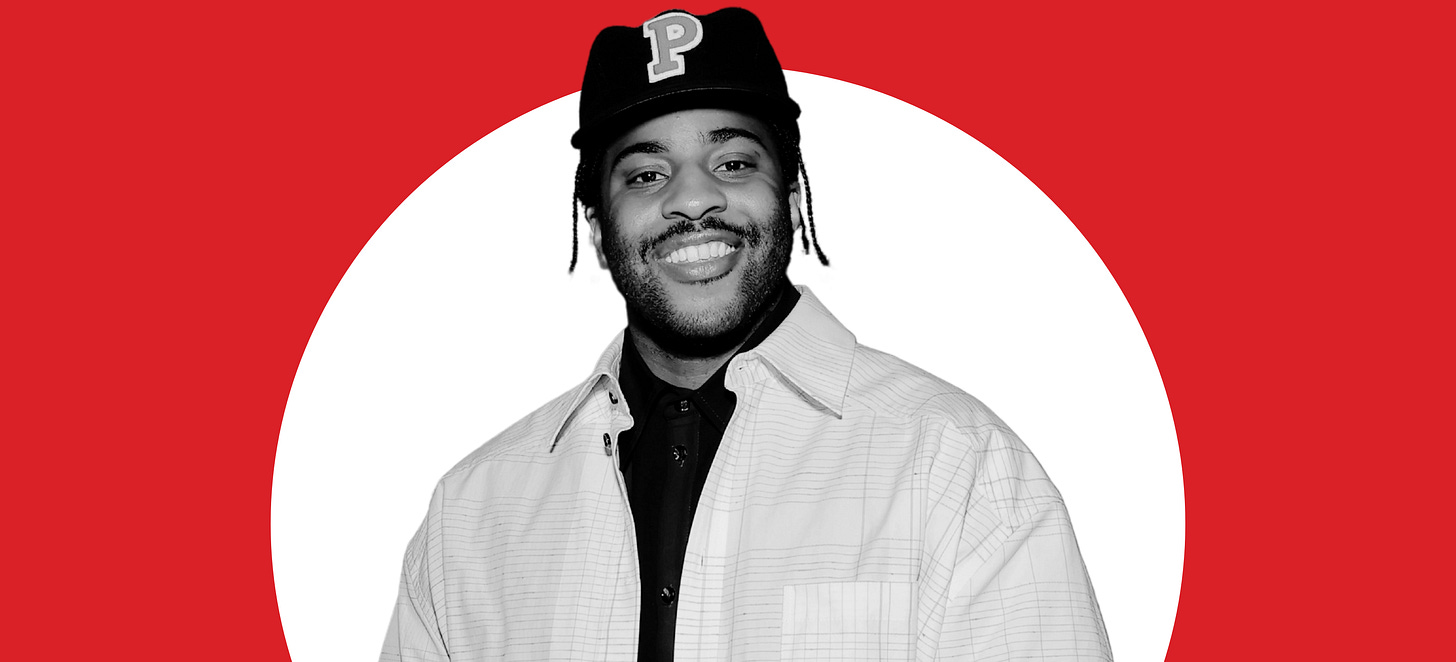

Director Malcolm Washington's 'Lesson': 'America Can’t Exist Without Black People'

The first-time director tells me how he made his explosive adaptation of August Wilson's 'The Piano Lesson' his own

I didn’t expect to talk to Malcolm Washington about the American experiment.

Before I got on Zoom with the 33-year-old director of The Piano Lesson a few weeks ago — yes, long before we knew how the election would turn out — I had the chance to revisit the film, and was bowled over once again by its audacious opening.

The adaptation of August Wilson’s play begins with a scene that doesn’t exist in the play at all but is referenced repeatedly by many of its characters. During a Fourth of July celebration near the turn of the century, a group of Black men steal a piano from a white family’s home. Their reasons for doing it become clear over the course of the play, but the scene plays out with virtually no dialogue: bright fireworks, booming sounds, men running away in the cover of darkness — and a young boy witnessing it all. (You can see glimpses of it in the trailer:)

Washington is making his feature-film directing debut with The Piano Lesson, and I wanted to ask him about this visually striking introduction, and how he found a way to add visual texture while remaining rigorously faithful to Wilson’s words. We talked about that, but also what it meant to depict a robbery on the Fourth of July when “America was founded on theft itself.”

Set in Pittsburgh during the Great Depression, The Piano Lesson reunites siblings Boy Willie (John David Washington, who is yes, Malcolm’s brother) and Berniece (Danielle Deadwyler) as they spar over what should become of the family’s heirloom piano, the very one we see stolen at the opening of the film. Much of the film’s ensemble first played their roles on Broadway in 2022, including Washington and co-stars Samuel L. Jackson, Ray Fisher and Michael Potts.

The most recent Broadway production of The Piano Lesson was a family affair, directed by Jackson’s wife, LaTanya Richardson Jackson. The film version continues that tradition, not only with the youngest Washington son directing the eldest, but their father Denzel Washington on board as a producer. Malcolm Washington undeniably arrives in Hollywood as part of a formidable legacy — but is also ready to define himself on his own terms.

In our conversation we talked about everything from learning about Michel Foucault while studying film at Penn to renting Ghostbusters from Blockbuster — and how it all fed into a film that he hopes will be the next step in an expansive series of August Wilson adaptations.

There will be a lot to discuss going forward about the impact of this week’s election on Hollywood and even the Oscar race — I’m working on some theories already, I promise. But for now let’s hear from a truly exciting new director whose thoughts on America’s unfulfilled potential have stuck with me for the past few weeks. I’ll hope you find something in them, too.

Katey Rich: So if you don’t mind, can we go really granular to start? That first scene is so bold in the context of the rest of the movie — the decision not only to open with a flashback and things that aren’t in the stage play, but make it really dramatic and vivid with these big, bright colors and big intense emotions. How did you figure out how to make that opening statement?

Malcolm Washington: This story is so complex. It’s a family drama with a ghost story kind of woven in between it. But underneath it there’s a really American story here about reclamation and retelling your story. We’re the third film of this series in a way (2016’s Fences and 2020’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom), and I knew that there would be certain expectations of what an August Wilson movie looks like, and I wanted to subvert those. I wanted to table set and say, hey, this is a new thing. This is a film, first and foremost.

We’re setting up these themes of Americana. It’s the Fourth of July, and America was founded on theft in itself. So to start this movie on this day with this color scheme and this action is hammering home what we’re standing on.

KR: It’s interesting that you think of it as being part of a series. Obviously August Wilson has this 10-play cycle, but there’s a way that you could be like, my movie is its own thing. It sounds like you embraced the idea that they were all connected.

MW: I think there’s so much beauty and power in that, right? All three of them are separate — they’re three separate filmmakers with different worldviews and skillsets, and I think that the filmmakers’ voices in each of these comes through. But there’s so much power in the idea of lineage in this way that these are all connected. If we get to make all 10 of them, or if all 10 get made, you can look back and see a story of a time, a story of a people interwoven with August.

(Fences was directed by and stars Denzel Washington; Ma Rainey was directed by George C. Wolfe.)

KR: When you say “we,” do you feel like you are connected to the effort to make all 10 of them in some way?

MW: Honestly, when I say we, I mean we as a culture. This belongs to a really proud culture of people, and this is about a proud culture of people. All of us get to own a piece of that. I think it’s important to take our stories and our heroes and take ownership over them in the way that the U.K. takes ownership over Shakespeare. [Wilson] is an American icon. He’s one of ours.

KR: I think a few people involved in this film have talked about August Wilson and Shakespeare. It makes sense as a comparison, but it can also really hamstring you, or make you feel like I'm stuck within the words that are here. With that opening scene, it's really clear that you're embracing the iconography of the words but not being trapped by them. Did it take a while to get to that point of knowing that you could work with them?

MW: No, that was the first thing. And I hate to use a comparison like that, because August Wilson is his own artist and he’s his own genius, and that should be celebrated independently of anybody else. But if you look at Shakespeare, if you really believe he’s that kind of person, Shakespeare is responsible for 10 Things I Hate About You. It’s like, okay, let’s adapt this, build on it. Let’s push it.

With this film, part of the idea was, Hey, I want all of these to be made. I want all of these to be relevant. I want it to make sense for all these to be made. So I want to start pushing at the boundaries of what these can be and show a new vision so that for the next seven, new voices can come in and push it even further than I did.

KR: But you’re also not going to set it, like, 200 years in the future, the way people would with Shakespeare. It’s almost like it’s early enough in the screen life of August Wilson that you have to keep the bones of it.

MW: You want to keep the spirit. And people that grew up on this story, people that revere this work — it’s like, hey, you’re here too. We’re inviting you too, but we’re also inviting your children and their friends, and all of these people should come.

KR: This is obviously a family project, with your brother and father involved, but so much of the story is about ancestors and family legacy. Did you have to figure that out for yourself, what legacy and ancestors mean, before taking this one?

MW: Of course. That's what I was doing when I originally took it on, I was trying to make sense of all those things. For me, our history in this country is an interesting one, and America’s such a fascinating experiment. It's like an incubator of the human experience, where there’s these great atrocities and huge secrets that the country holds, but also great promise. You wrestle with all of these things, where the African-American experience is so singular to the American experience. And when I say America, I include the islands and Central America and South America. We all have a shared history in that way.

When I look at my ancestry, I think of how these heroes of mine, these figures that cast this large shadow over me, their lives were possible because of America — in spite of it, wrestling with it, combating it, confronting it, and ultimately creating it at the same time. Their blood and sweat is the backbone of what built this place. So I feel like I have as much pride and ownership over it as anybody.

KR: So when you include the Fourth of July in the opening of this film, is there patriotism in there, too?

MW: Yeah, it’s a reclamation. America can’t exist without Black people. It can’t exist without our labor, without our ideas, without our creativity of course. So there’s inherently a patriotism there, and I think that that’s important. I think the way that the sound design works to me tells that story, right? You hear these big bombastic fireworks and they sound like drums when we’re with the white picnic. Then, when we’re with the Black people, our characters, those fireworks turn into bombs. They’re percussive and violent and scary. This is the truth. This is what the place really is.

KR: Has American history always resonated with you in that way? It feels like you’ve been thinking about this stuff a long time.

MW: Yeah, it has. I think we all have this idea of, what’s our place in the world? Do we exist in it? Is there space for us? And then some days you think, oh yeah, there’s no space. They don’t teach our story. Then you come to the terms of, Wait, a lot of people fought for my space. I do have a space in it. I have a stake in it. There’s a lot of people that put their lives on the line to make that possible and to say that you don’t ignore their struggle, that’s their victory. This is the most current state of a long period of gestation on this concept.

KR: You’ve said that even though this is your first film, you’ve been a filmmaker for 33 years. Does that mean working with these ideas in your head, or playing with a camera, or what?

MW: Yeah, I would always hear stories of like, oh, such and such filmmaker got a Super 8 camera when they were six years old. So if you’re a filmmaker, you must’ve been shooting home videos since you were a little kid. That’s not my experience at all. What I learned in college actually was that films are presumed to talk about other ideas, bigger ideas, philosophical ideas, historical ideas. So a big part of my coming to be as a filmmaker is me wrestling with ideology itself, wrestling with worldview, figuring out my worldview, what do I think about all these things?

KR: Do you feel like growing up with your perspective on the film industry that you had to get away and discover it for yourself in some way?

MW: Maybe, but I think that people have a different understanding from what my childhood actually looked like. They romanticize it, like, oh, I’m on set all the time. A set is no place for a child. I grew up in the Valley. I grew up riding bikes in the cul-de-sac and going to Blockbuster and watching movies with my family. I was watching Friday and Ghostbusters. This is what we were watching. I wasn't sitting down with Ed Zwick (who directed Denzel in Glory, Courage Under Fire and The Siege) picking his brain as a 6-year-old.

So when I got to college, it was like, oh wait, talk about Foucault and (Jacques) Lacan. Or let’s learn about Balkan history through Balkan cinema. I didn’t know you could even think like that.

KR: So what was the learning curve of stepping onto a set and knowing everything you wanted to say, but then being the director and having to make it all happen?

MW: I think that’s what was so exciting. I have a big family — I have my siblings, my cousins, there’s always a lot of us. I just always enjoy that energy of so many people coming together to do something. I could spin out all day thinking about it and just in my own head. So having other people come in and bring what they have to it and their life experience, it just raises the ceiling every time. Especially if you work with people who you trust and admire their work and where they come from and who they are as people.

That’s one of my favorite parts, collaboration. I see it with my friends who are musicians. They live in a little bit more of a vacuum. For me, we spend the majority of our time talking about other stuff, and then when it’s time to work, you can just go, because you know each other and you have these ideas, like, “Remember when you were a kid and your dad put his hand on your back and his hand felt so heavy, but you felt protected? That’s the feeling.” So we invent that image from a memory that we discussed, and it has a resonance in the movie because it comes from truth.

KR: Most of the ensemble of The Piano Lesson had already worked together on Broadway. What was it like building your relationship with each of them and becoming part of this group?

MW: It is just watching. I feel like so much directing is just watching. Watching people, watching how they move through space, watching how they take information in, watching how they express themselves. You want to cast the best people for the part, the best people that you want to work with, that work within this team. And then you want them to be free.

Because being an actor is such a scary thing. You have to submit yourself, your image, your voice — personal parts of yourself — to the filmmaker. Because I go off and I cut the thing and I choose the takes, and I have a hand in that performance as well. So you have to have a lot of trust. So I want them to know me and what I’m after too, because we're both submitting to each other in that way.

KR: You sound like someone who does not want to follow your father or your brother and be an actor.

MW: It’s not my calling. I’m in this stage of this rollout of doing photo shoots — I get exhausted by them. After 10 photos I’m like, alright, can we go home now?

KR: Can you not get advice from the actors on how to pose?

MW: They’re all like models! They’re the most handsome, confident — I’m sitting with Danielle, and Danielle’s like, oh my God, this is so annoying. And then she hits the Vogue show. I’m like, what are we talking about!

KR: Well, you cast gorgeous confident people, so I guess you only have yourself to blame.

MW: Now I’m trying to hide behind them in the photos.

Nepo-baby makes good