Brando, Beatty and Connie Chung's 7 Wild Years in L.A.

In an excerpt from her 'New York Times' bestseller, the legendary newswoman reveals her rollicking ride as the pursued (and pursuer)

Today’s Ankler Rewind comes from Andy Lewis, writer of The Optionist, a weekly newsletter about available IP on the market.

Connie Chung became a young rising star on TV news in the 1970s, breaking big stories on George McGovern and Richard Nixon and delivering one Watergate scoop after another while working out of CBS News’ Washington D.C. bureau. Though the nation’s capital is an industry town, nothing still quite prepared her for life in another one, this time on the left coast. From 1976-1983, she co-anchored the nightly news on L.A.’s KNXT (now KCBS). Not only was it a premier steppingstone to a national network job, it came with a perk unlike any other local news job — entree into the rarefied world of Hollywood celebrities.

In Connie: A Memoir, Chung recounts living in a garden apartment just off Sunset Boulevard (once occupied by Vivian Vance and across from David Niven, Jr. — this is Hollywood after all), flirtatiously going around (and around) the same revolving door as Warren Beatty at the Beverly Wilshire one night and later dating him, and daring Ryan O’Neal to follow her home after a party at Swifty Lazar’s. (It seems he did.)

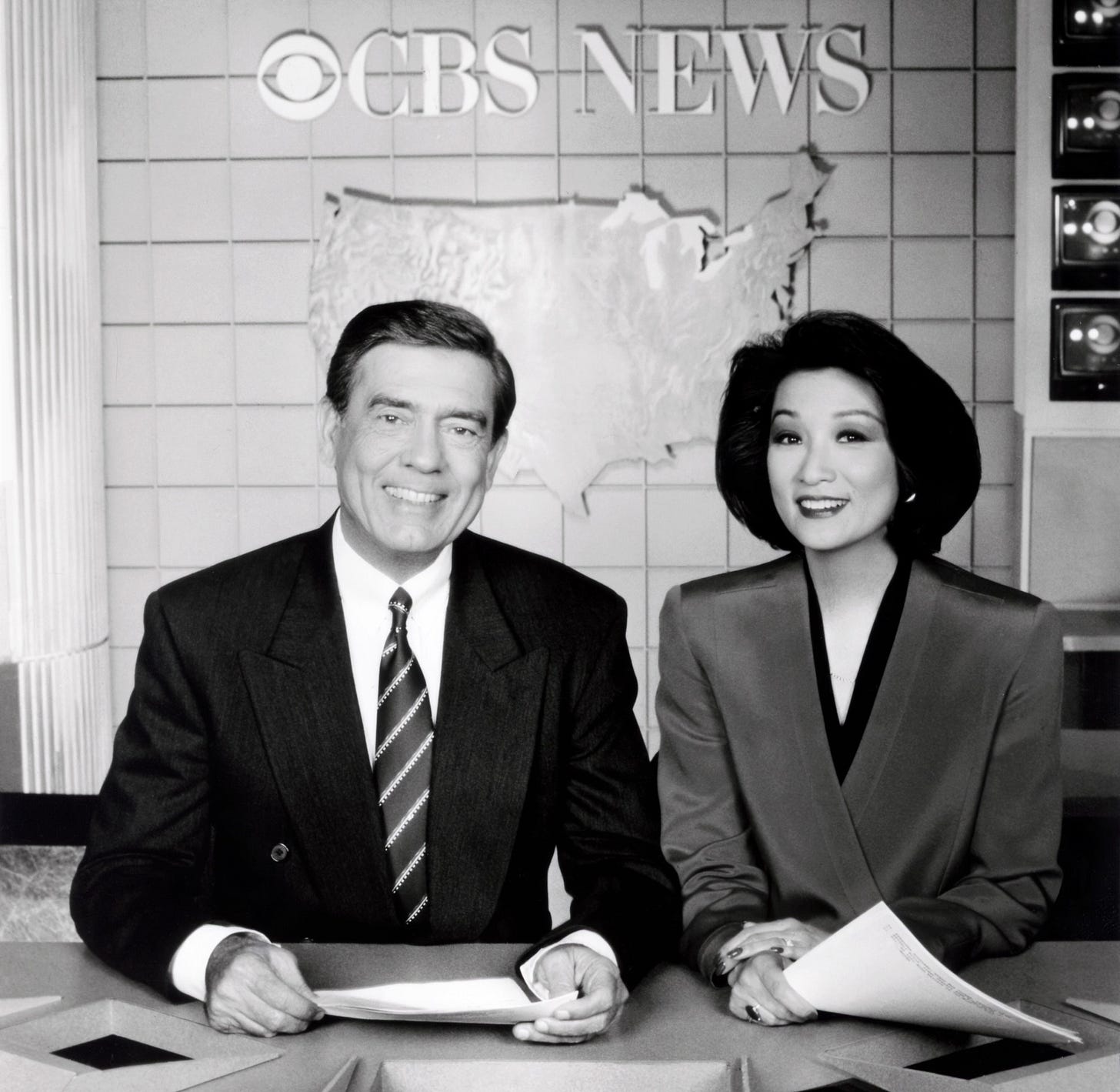

Later she would head to New York and break barriers as the second woman and first Asian-American to anchor the nightly news on a Big Three network, CBS in 1993, at the peak of broadcast news, a far cry from today.

Those years in L.A. laid the groundwork for her later seminal interview with Marlon Brando, an Emmy-award winning piece but one that would forever sour her on the games played around celebrity interviews.

Let’s start at a party circa 1979 at Beatty’s house: Chung first met him in 1972 at a dinner party at Senator McGovern’s house during his campaign for president. Here Beatty, using all his legendary charm, is pursuer, despite Chung’s deepening relationship with her future husband Maury Povich. Then we move to a party at Swifty’s — and a night out with the Eagles.

Herewith, an excerpt from Connie: A Memoir, in her own words:

L.A. Roundabout

Scene: the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, where I was exiting through a revolving door. Entering through the revolving door: Warren Beatty. We circled around a few times, laughing at the silliness. Remember Beatty? He was the one who chased every skirt on the 1972 McGovern campaign. I was a dedicated reporter who did not want anything to taint my reputation. I resisted his overtures.

Now I was in La-La Land and Warren was relentless. What the heck. He actually lived at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel in a small room on a top floor, tucked in the eaves. We went out a couple times and he called often. There were times when he rang me at my apartment when Maury and his daughters were visiting me. One day, either Susan or Amy answered my phone. Her eyes bugged out when she whispered to me that Warren Beatty was on the line. She added, “We won’t tell Dad.” How cute is that? From then on, if Warren called and the girls were at my apartment, they would say, “Connie, it’s Walter!” — their code name for him. They were and are the best.

After Warren built a huge house at the top of Mulholland Drive, he threw a party to screen a current motion picture. That’s how Hollywood celebrities viewed new movies — in the comfort of their homes, where they had large screening rooms. A projectionist would be hired for the night. Celebs no doubt believed going to movie theaters was for the masses.

Warren invited me to the party at his house in the Hollywood Hills. I could not help but notice that the women far outnumbered the men. Could it be that the women thought it would be a slumber party for two? I knew no one except Warren. While we watched the movie, I started to notice something strange. Why was everyone getting up, going somewhere, and returning just a couple of minutes later? They were missing the whole film. What was going on? Someone later told me they were probably doing cocaine. I was so naive about drugs.

I did not even know that a tube was used to snort coke, but I soon found out. A friend of mine, Karen Danaher Dorr, who had been an audio person at CBS News in Washington, was now living in Los Angeles and working as an executive in film. She called me after she experienced the trauma of being raped. Fearful to stay in her home, where the rape occurred, she asked if she could stay with me. Of course I offered her my spare bedroom. Knowing many people smoked marijuana then, yet not knowing if she did, as a precaution, I asked her to keep drugs out of my home. One night I had dinner with an old schoolmate, who joined me at my apartment afterward. The next morning Karen came to me with a small glass tube in her hand. I asked her what it was. "I found it in the Kleenex box in the spare bathroom,” she said. I looked at her with a blank expression on my face, and suddenly her eyes widened. “You don’t know what this is, do you?” That was how innocent I was. I did not know it was used to snort cocaine. She grinned.

Irving “Swifty” Lazar was a powerhouse dealmaker packed in a small man with oversize black-rimmed glasses. Lazar was a talent agent extraordinaire for stars and authors from Cary Grant to Lauren Bacall, Gershwin to Cher, Hemingway to Capote, and even Richard Nixon. Humphrey Bogart had nicknamed Lazar “Swifty” after the agent sealed three deals for Bogie in a single day.

Swifty was known for throwing legendary parties. After seeing me on the news, he and his wife invited me to a dinner party at their home in the Hollywood Hills. Their house was decorated as beautifully as a grand Fifth Avenue apartment, filled with lots of antiques and chintz. I was starry-eyed at the gathering of glitterati.

To my shock and delight, I found myself chatting with my ultimate heartthrob, Gregory Peck. I had probably seen every one of his motion pictures. Yes, his voice was as deep and his face as handsome as on the big screen. As I stood there with him, the newspaper reporter he’d played in Roman Holiday came to life before my eyes. His character snookers a princess, played by Audrey Hepburn, into a night out in Rome, creating a scandal for her and a scoop for himself. But he falls hopelessly in love with her and refuses to submit the damaging story for publication. “Oh my,” I thought, “a journalist with a heart” — Gregory Peck and I had something in common! I certainly would have given up my princess-ship for him. Alas, Peck shook me loose from my daydream by introducing me to his statuesque, elegant wife, Veronique. I had never felt so short.

When I went to refresh my cocktail, there stood the great Billy Wilder. He was much more than a brilliant director, he was also an unparalleled screenwriter —Ninotchka starring Greta Garbo, Sunset Boulevard, Stalag 17, and Some Like It Hot, just to name a few. I had seen them all. Wilder told me he watched me on the news and was incredibly enthusiastic about meeting me in person. I could barely contain myself. He took me by the hand to meet Jack Lemmon, whom Wilder had directed in The Apartment. What a treat it was to shake the hands of Lemmon, his wife, Felicia Farr, and Walter Matthau and his wife, Carol Grace. We all sat in an enclosed patio with white latticework and chairs covered in Lilly Pulitzer pink-and-green fabric. The Odd Couple chatting it up with a little local news anchor.

All night, I kept getting glimpses of Ryan O’Neal, who was looking very Love Story-ish. Our eyes met several times during the night, but I never seemed to be able to gracefully weave through the stars to talk to him. Before I knew it, the night was over, and everyone was heading to the door to give hunky wannabe actors our valet tickets so they could run and get our cars. I found myself at the door just in front of Ryan O’Neal. I looked at him and a line from old black-and-white movies emerged from my lips: “Your place or mine?” O’Neal replied, “Up to you.” With a subtle and casual glance back at him, I said, “Follow me.” I hopped in my black Jensen-Healey convertible, gunned my motor, and scooted down the hill — waiting for him down the road. Feel free to use your imagination.

One night a girlfriend of mine and I decided to go to dinner at Musso & Frank, a small, funky restaurant on Hollywood Boulevard. We settled into a booth, just the two of us. Not far away, at another booth, were four guys. They asked if we wanted to join them. “Sure.” We nodded, squeezing into their booth.

They seemed nice, smart, fun. I asked the guy I found most appealing what he did for a living. “I play in a band.” At the end of the dinner, he asked me if I wanted to go to his house. “Sure.” In his cluttered living room, an upright piano took a prominent spot. “Would you play something you perform with your band?” I asked innocently. “Sure.” He launched into “Hotel California.” Gulp.

By this time, Maury, who had gotten an anchor job in San Francisco, had already moved on to the NBC affiliate in Philadelphia, where he was a news anchor, reporter, and talk show host. We were still a two-city couple, but the long travel time between L.A. and Philly slowed our romance. Still, we talked frequently. I called to tweak him: “I went out with an Eagle.” Maury replied, “You mean the Philadelphia Eagles?” How I groaned.

Marlon and Me

By 1989, Chung was back at CBS in New York, with her own show, Saturday Night with Connie Chung, but her L.A. contacts were still paying dividends. A professional but peculiar relationship with Brando that started when she was at KNXT, and was conducted mostly through late-night phone calls, yielded an 1993 infamous sit-down interview with the reclusive actor that simultaneously won her the first of her three Emmys — and had her questioning her career.

Saturday Night with Connie Chung remained a ratings cellar dweller no matter what we did. Then one day, I got a call from Marlon Brando, the Hollywood uber legend, who had won wide acclaim portraying Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now, and of course Don Vito Corleone in The Godfather. He called to grouse about a film in which he appeared, A Dry White Season, about apartheid in South Africa.

He accused the director of watering down the antiapartheid theme and ruining the film in editing. This was not the first time he had called me. As you know, I had anchored local news at the CBS station in Los Angeles. One evening, I’d stepped off the set after The 6 O’Clock News when someone told me I had a call.

“Connie, this is Marlon Brando.”

“Sure, right,” I said, certain it was a joke.

“Why don’t you continue talking? I’ll decide if you are Marlon Brando.”

He started to ramble about Indigenous Americans. While listening to him, I remembered that he had refused to accept an Oscar, his second, for his role in The Godfather. In his place, Brando had sent a woman named Sacheen Littlefeather to read a statement he had written. Littlefeather claimed to be an Apache, though after her death in 2022 her sisters disputed this. Brando was protesting the portrayal of Indigenous people in movies and on television. The voice sounded just like Brando’s. And he was speaking as if he had a few marbles in his mouth. Could it really be? Indeed, it was.

The calls at work kept coming until I finally agreed to meet him for a drink after work. Brando was rumored to have an Asian fetish, which gave me pause. But I was much too curious. “Meet me at Le Dome on Sunset,” I said. “After I get off The 11 O'Clock News. I’ll be there around midnight.”

As I entered the restaurant, I didn’t need to look around much — I couldn’t miss him. Marlon Brando was no longer the irresistible young man with piercing eyes, full lips, and a brooding, sexy look. He was a round-faced, terribly overweight man who was poured onto a velvet banquette. I said hello with a hesitant smile on my face, not knowing what to expect.

What did we talk about? Damned if I remember. He probably did most of the talking. After about an hour, I said goodbye and drove home.

As the years passed, I had given him my home phone number (never my home address), hoping to cajole him into doing an interview. He left interminable messages on my old-fashioned answering machine. Sometimes he would use up the entire cassette. I kept one cassette, which I cannot find now, in which he mumbled forever about taking me down the Nile. He also asked what I wear to bed at night. I told him flannel pajamas with feet. When Maury and I started dating, Brando was still calling. Once, Maury picked up the phone, but that did not prove to be a deterrent to Marlon the Persistent.

After years of phone games and me coaxing him to sit down for an interview, Brando finally said yes, provided he could vent about A Dry White Season. It was to be his first interview in 16 years. When our 10-person team — including two camera crews, CBS still photographer Tony Esparza, producer Chris Dalrymple, and me — arrived at his home in the Hollywood Hills, Brando’s assistant, an Asian woman, had laid out quite a spread of food for us. Brando insisted we eat before we set up.

We chose his beautiful patio for the interview. We settled into garden chairs, and for the next six-plus hours, while we rolled many tapes, he toyed with me and never gave me a serious answer to any of my serious questions.

Brando denigrated his craft as if his work had been frivolous. He was evasive as I asked him to acknowledge and discuss his successes. He had been trained by the masters of Method acting, Stella Adler and Stanislavski. He was idolized, even worshipped, by other actors. I pressed him, but he waved off his whole career and the entire industry as superficial, refusing to respect his profession. He said, “It’s a waste of time. I don’t find it stimulating or interesting. It’s not a consuming passion.”

Brando continued to scoff. “I find it odious, unpleasant. I don’t find acting satisfying. I’m much more interested in writing. Focusing on other things.” “Such as?” I asked.

“I’m interested in everything. I've spent hours and hours watching ants go up and down my sink. Picking up crumbs and finding out where they come from.” What the heck was he talking about? He went off on wacky tangents. I tried to remain composed, despite his bizarre behavior.

We had talked for so long, the sun had set, the light dropping dramatically to darkness. The crew had to set up lights on the patio. I kept at it, even though I was at my wit’s end, trying over and over to squeeze some substance out of him. But I never did. While writing this book, I discovered on YouTube an interview Brando did with talk show host Dick Cavett on June 12, 1973. Brando played cat and mouse with him too. Like me, Cavett gave Brando a forum for his favorite cause: how Indigenous people were shown in movies. Cavett even invited several tribal leaders on his talk show, no doubt quid pro quo for the actor. But Brando did not reciprocate. When Cavett asked him about The Godfather, the recalcitrant Brando responded, “I don’t want to talk about movies.”

Had I seen Cavett’s interview before I sat down with Brando, I would have been forewarned. Too bad YouTube wasn’t invented then.

Thanks to the internet and my researcher John Yuro, I was able to read a transcript of Brando’s interview with Edward R. Murrow on Person to Person on April 1, 1955. Brando was only 30 at the time. The interview was as inane and mortifying as mine. Murrow asked, “You heard any good stories lately?” To which Brando replied, “. . . What time is it when the Chinaman goes to the dentist?" Murrow played straight man. “What time is it when the Chinaman goes to the dentist?”

Brando delivered the punch line. “ . . . Well, it’s tooth dirty. You know? Two thirty.” Frankly, I was not at ease interviewing Brando because he was looking at me as if I were a nice cut of Asian meat. He had several children with an Asian woman. It was not hard to see he had a fetish.

When the Brando interview aired, it proved to be a ratings bonanza, even on a Saturday night. I was surprised that the actor touched a nerve with a cross section of people — Hollywood actors, neighbors, people I had not heard from in years, people on the street, Warren Beatty begged me to give him a copy of the raw tapes. I never did.

Although I won an Emmy for Best Interview, I thought it was an awful encounter, and it soured me on the idea of interviewing actors. Barbara Walters once said she liked doing celebrity interviews because they are both entertaining and informational. I did not see the purpose. I preferred serious news. Actors and actresses typically agreed to interviews to promote their movies. They usually didn’t want to reveal their innermost thoughts, and why would we want to pry anyway?

Shortly after the Brando interview aired, Maury and I were invited to a White House State Dinner for President of Italy Francesco Cossiga. Out of more than a hundred guests, I was honored and flattered to be seated next to President George H. W. Bush. I had covered him when he was a member of Congress, chairman of the Republican National Committee, and head of the Central Intelligence Agency. When he was chief of the liaison office in China, he wrote me lovely letters.

At the state dinner, I engaged in small talk with President Bush. No doubt he had been briefed about my interview with Marlon Brando. “So, Connie,” he said, “I hear you had a big interview. What was Yul Brynner really like?” I didn’t want to embarrass the president, so I answered with a straight face, “He was not what I expected.” Someone at our table must have overheard it and reported our conversation to the Washington Post. The next morning a Post columnist called me. “Is it true that Bush asked you how your interview with Yul Brynner went . . . but it was Marlon Brando you interviewed?” “No, that’s not correct,” I replied with no hesitation. I could not throw President Bush under the bus. After all, it wasn’t Iran-Contra.