Billy Idol: Snarls, Scars & a Wild Chat with the Rollicking Rock Icon

'I should be dead with everything that I did to myself,' the punk legend tells me in advance of his documentary debut at Tribeca

I write about where music and Hollywood meet. I interviewed Oscar winner Gustavo Santaolalla about bringing humanity to The Last of Us and spoke to White Lotus composer Cristobal Tapia de Veer about his feud with show creator Mike White. Reach me at rob@theankler.com

For several years now, the Tribeca Festival in New York has been noteworthy for its anniversary screenings of Martin Scorsese classics and for Robert De Niro sometimes giving monosyllabic interviews, sometimes on the same night. (Last night, I attended a special 30th anniversary screening of Casino, where moderator W. Kamau Bell had the honor of chatting with the longtime collaborators and friends.)

But along with its filmmaking pedigree, Tribeca perhaps holds the distinction as the most music-forward film festival around, regularly featuring a wide slate of projects focused on musicians, where premiere screenings are often coupled with live performances.

This year is only slightly different. Tribeca opened with the world premiere of And So It Goes…, the Billy Joel doc coming to HBO this summer that has arrived under poignant circumstances due to his recent medical diagnosis of normal pressure hydrocephalus. While the Piano Man was understandably M.I.A. on Wednesday night, he did relay a message to the capacity crowd at the Beacon Theater: “Getting old sucks, but it’s still preferable to getting cremated.” (While Joel was absent, big names who held down the fort at the screening and subsequent afterparty at Tavern on the Green included De Niro, Tribeca founder Jane Rosenthal and Tom Hanks.)

Beyond Joel, however, are a lengthy list of other musical projects in the Tribeca lineup, running the gamut from pop superstars (Miley Cyrus unveiling Something Beautiful, the companion film to her brand new album of the same name) to indie stalwarts (Counting Crows: Have You Seen Me Lately?), ’80s icons (Boy George & Culture Club) and electronic trailblazers (Depeche Mode: M) just to name a few.

There’s also the world premiere of Billy Idol Should Be Dead, the wild and surprisingly heartfelt documentary from Live Nation and celebrated music video director Jonas Åkerlund. The film leaves no stone unturned in telling Idol’s improbable story, which saw the singer go from a Sex Pistols fan who butted heads with his father to a global icon, unflinchingly relaying the harrowing times when he nearly died from overdosing; scenes illustrated through the film’s novel use of graphic-novel style animation.

Ahead of the doc’s premiere in New York on Tuesday — after which Idol himself will perform — I had the chance to talk with the rocker about his unruly career.

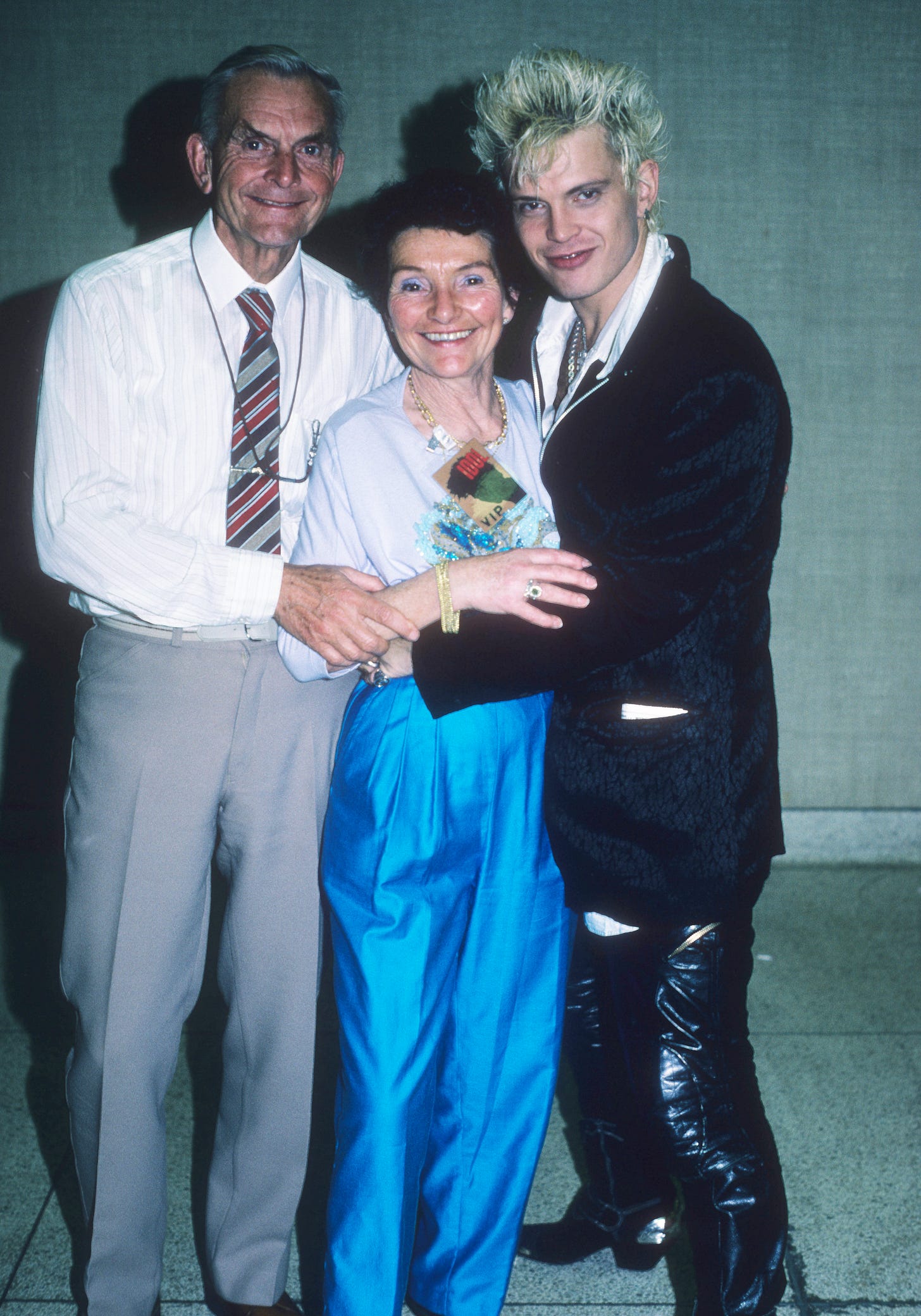

Sure, I knew Idol’s rollicking reputation and personal history. Born in London to parents William, a power tool salesman, and Joan, a former surgical nurse, Idol — whose real name is William Broad — moved to Long Island with his family when he was a toddler, before eventually heading back to the U.K. for most of his formative years. Once he started performing in the late ’70s under the moniker Billy Idol, it wasn’t long before his trademark snarl, rockabilly hairdo and classic tracks, including “White Wedding” and “Eyes Without a Face,” launched him to stardom.

But as he approaches 70 later this year, Idol is in a ruminative mood. Unmarried and living in Los Angeles, he’s a grandfather now and often posts about his family on social media. Perhaps that’s why he’s spent so much time reflecting on his eventful life in both the documentary and Dream Into It, his recent ninth album and first in over a decade. Featuring collaborations with mentees like Avril Lavigne and Joan Jett, its lead single is the aptly-titled “Still Dancing,” whose video has collected a million views on YouTube.

Here’s someone who lived on the razor’s edge and lived to tell the tale, a rare honor among many of his peers who, as he’s wont to say, “didn’t make it out.” I began our lively conversation from there.

Rob LeDonne: Billy Idol Should Be Dead. That’s one hell of a title, man. Was that pitched to you? Because that’s a ballsy name to propose.

Billy Idol: Well, it’s one of those things that people usually say when they don’t realize I’m still alive. They actually say that: “Isn’t he dead?” Yeah, I should be dead with everything that I did to myself. But it just made me laugh; the idea of that as the title.

It works on so many levels because it’s true, it’s funny, but it’s also deep, like the documentary. Was that the goal?

BI: Yeah, it does work on different levels. I think the documentary has got a depth to it, as we really worked on it over quite a long period of time, mainly because the coronavirus was going on while we were making it. It kept getting stopped for one reason or another from the different waves of the virus. But actually it really helped the documentary in the sense that we were able to massage it and really look at what we had and realize what we needed. I think we’ve got something really good. I think it’s a really great documentary that shows a lot of aspects of my life.

What was it like putting a warts-and-all film together like this? I’m thinking about the scene where you nearly overdose in New York and the people around you describe getting these late-night calls. I imagine that it takes some vulnerability. Did you ever want to hold back?

BI: Well, there are things like that in the documentary, but we just had to go there. You just have to own it and you realize what happened, whatever it was, the drug addiction or whatever else and own the different periods of my life. It all led to something: The bad stuff and the good stuff somehow ended up fusing [into] the music I’ve made.

You’ve often said about your peers that “a lot of people didn’t make it out.” What kind of state of mind does that thought put you in? Because I know some people who truly appreciate life because of that, and others carry a guilt that they made it when so many others didn’t.

BI: Yeah, [embracing life] is kind of where I am. It’s great that I had children because the grandchildren are a lot of fun. But I was lucky, really, because I got to live the life I wanted to live. I got to do the thing I love. Most people don’t get that chance. You know, punk rock changed the playing field with music because you didn’t have to be the greatest musician anymore. You didn't have to be a great singer. Looking at musicians like Paul McCartney, we were looking at that going, “Wow, how do you compete with that?” And then we realized, let’s just change the fucking playing field. We were never thinking it was gonna explode into something huge.

When The Sex Pistols went on this TV show and they swore, this truck driver put his boot through a television set, and the next day every kid in England wanted to be either in a punk rock group or be a punk rock fan. But it just shows you if you do the thing you love, you get paid back. And that's kind of what’s happened throughout my life. That in itself is a huge payoff because most people aren’t doing the thing they love. They're living for the weekend or living for the day they can retire and do the thing they love. Or, the thing they love is a hobby.

Pursuing your interests led to this complicated relationship with your father. For a time, when you were younger, he gave you the silent treatment. One thing you’ve said that blew me away was, “It’s a shame that sometimes, by doing what you’ve got to do, you hurt the people you love. But, if you don’t do it, you’re going to let them down because they won’t know the real you.” I think that’s the main crux of the doc, right there. Would you agree?

BI: Yeah, it is very true. In a way, I frightened my parents to death. You hurt people when they don’t understand what you are as a person, when they don’t know the you inside, really. Then the day you kind of start doing the thing you love, they’re kind of a little bit shocked. Some people in my family were repulsed by what I was doing, and I was almost a pariah for a bit. My parents couldn’t understand punk rock. But there were other sides of my family who did; the Irish side kind of got it. But the English thought it was low-class. Like “He's crazy! How could this man be doing this?”

But you need to have that madness. You need to set fire to yourself, or otherwise you won’t do anything in life, and then you won’t be proud of yourself. At the end of the day, I’m proud that I did that. I struggled through moments when they were difficult. The songs aren’t always easy, but you have to live life to write the song. So you kind of know you have to go through things, and the songs will appear, and that’s what happened. I couldn’t have known that at the beginning. I didn’t know it at the time, as we were doing it. It’s only over time that you start finding out, “Oh, because I did this, that happened.” Because I did these things all those years ago, I’m still here. But that quote was great. I'm glad I said that.

I was expecting the doc to focus on the wild stories. However, what surprised me was your story with your father, which was truly touching. In the end, you say you related to him because you realized he was a salesman, and in a sense, as a performer projecting a particular ethos on the stage, you are too. Can you explain that?

BI: Yes. I mean, in lots of ways, I started to realize I’m not so different from my dad. I just had to find the thing I wanted to sell in a way. I went around with him when he was selling, and I saw his charisma. He would turn his lights on, you know? I would be like, “Wow!” He would be friends with the people he was selling to; he looked at them like they were friends. A side of him came alive when he was selling that I didn’t see. I’m so sad to really think about it. I’m not so different from him in the end, you know?

It’s like you were saying the same things in a different language. There’s the truly harrowing scene when you’re in the hospital after your drug overdose. Your father wanted to come and visit you, and you said, using your given name, “the William Broad part of you” wanted him there, but “the Billy Idol didn’t want him to come.” Was this dance between your real self and your alter ego a constant balancing act?

BI: Yeah. Not that we are two different people or anything, but the Billy Idol side is kind of outgoing and enables me to be on stage. Of course, when I first went on stage, I wasn’t used to it, so it was like, “Whoa!” But over time, you realize you’re meant to be doing this. There’s something inside me that I can overcome, my self-consciousness or whatever it is. But then there’s the little boy that my dad knew. When I was young, my dad and I were really good friends; we loved each other, you know? It was only when I was a teenager that things really went sour, and they stayed like that for a long time. It was kind of horrible, really. But I was glad they cared about me and that they were worried for me.

Isn’t that funny? At the time, you think your parents are holding you back, but in reality, they were just afraid for you.

BI: They kind of knew what rock and roll was, but he didn’t know what punk was. It frightened them to death. That’s what the song “People I Love” on the new album is about. But my mom always kind of got it, ‘cause she’s Irish and into music. But my dad couldn't understand. “Why would you wanna do that?”

What music did your dad listen to?

BI: He didn’t really listen to music. My mother loved jazz and people like Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, Count Basie, Miles Davis and Duke Ellington. She had all those records. I learned a lot from Richard Burton doing Camelot because I found out you can speak in a song. He spoke-sang his way through that show. “I wonder what the king is doing tonight…”

RL: That’s an incredible song, and in a way, lines up with the punk ethos. Isn’t that song about how authority isn’t what it seems? The king is stressed, scared and clueless. Punk doubts leadership in the same way. Like, “You don’t know what you’re doing, so burn it all down. Who cares?”

BI: Yeah, that is what we thought. We thought that older people are not leading us anywhere, so we’ve to lead ourselves.

Speaking of, considering the strife in the world, do you think the punk scene could ever be reborn?

BI: Yeah. It may not be with the same instruments or something, but I would think the way society is and the kind of government we’ve got at the moment. I think very much, there must be a lot of pissed off young people out there. I wouldn't be surprised if there isn’t some kind of movement created by the political scene we’ve got at the moment. Because I think people are searching for a way to go and not really finding it, you know? So that always breeds discontent, which will end up with someone putting it into music.

I wanted to ask you about one of the best Saturday Night Live sketches of all time, which is “The Sinatra Group” with Phil Hartman as Frank, written by Robert Smigel. In it, Sting impersonates you, snarls and everything. What did you think when that aired?

BI: Well, I thought it was really funny. I was told a story: Sting’s wife, Trudie, told me that when he went into the dressing room after playing me, she got him to have sex with him as me. So that was a great caveat to the sketch. She said, “Fuck me as Billy Idol.” And he did.