Barry Diller: 'I Never Said Legacy Studios Couldn't Thrive in the Future'

The mogul responds when asked about his 40 years of trash-talking Hollywood and the movies as he enters the fray for his one-time home: Paramount

After former Paramount Pictures CEO Barry Diller lost out to Sumner Redstone and Viacom in 1994 to purchase Paramount after a six-month battle, he issued a legendary terse statement:

“They won. We lost. Next.”

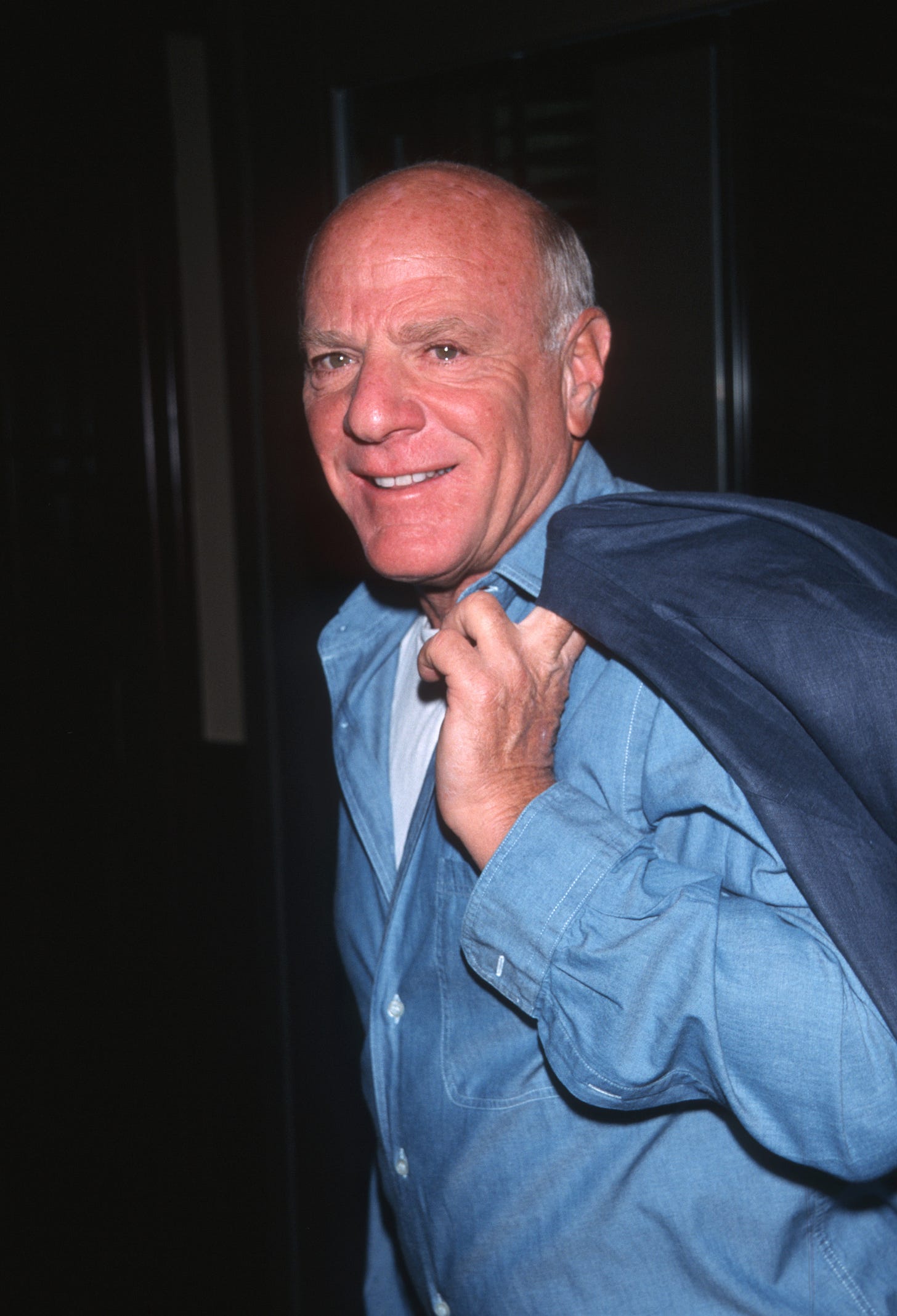

Flash forward 30 years and “next” for the ever-restless Diller is . . . Paramount! On Monday, The New York Times reported that Diller — through the holding company he chairs, IAC — is exploring a run at the troubled media conglomerate, whose stock has dropped 80 percent in the last five years and 28 percent in 2024 alone.

Befitting Hollywood’s current reboot fever, the Paramount sale drama now has a beloved favorite from the 1994 OG version returning to reprise his role. Think of it like Judge Reinhold’s character from the original Beverly Hills Cop (a movie Paramount made when Diller was chairman in the early 1980s) returning to mix it up in the 2024 revival Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F.

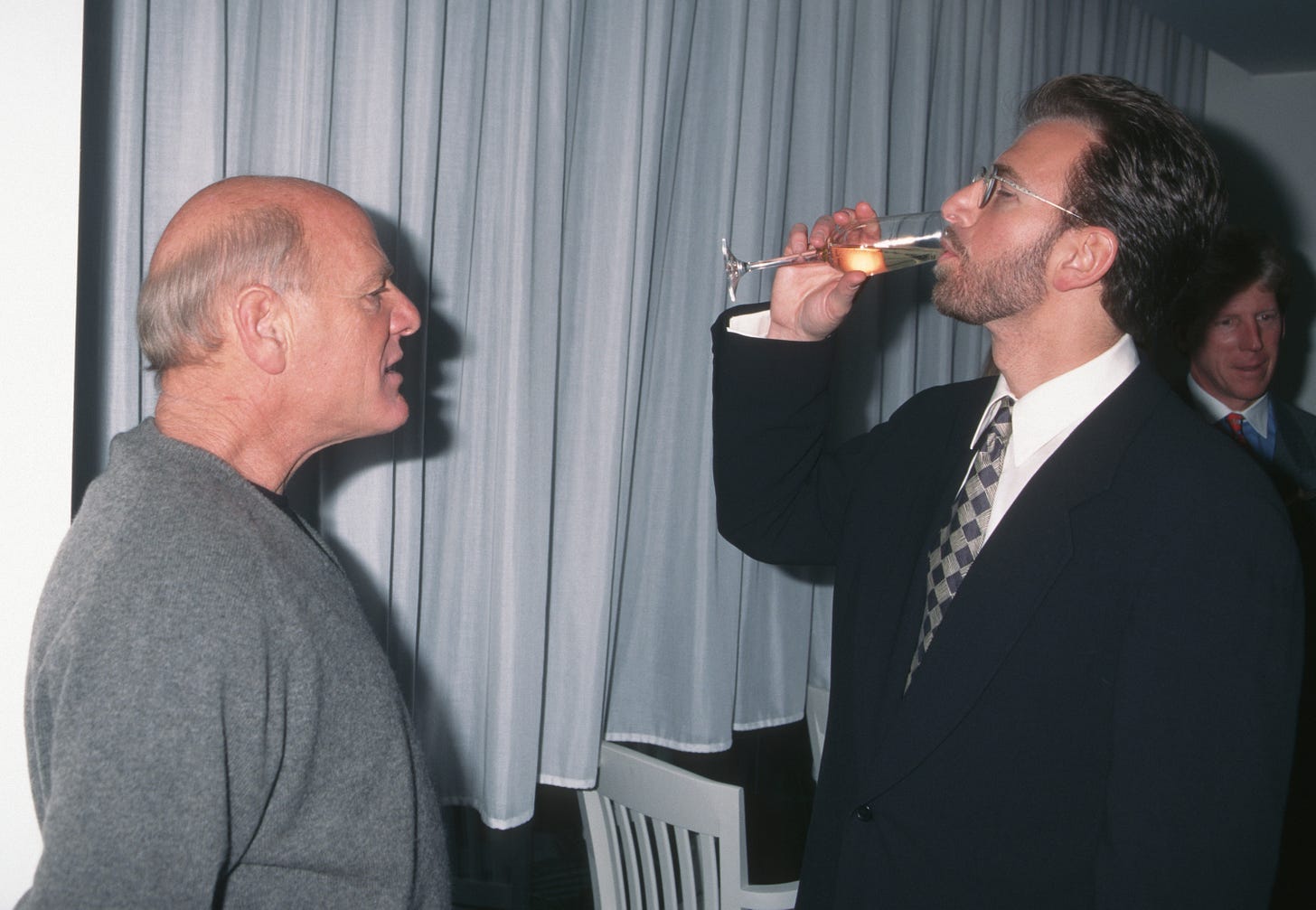

Diller returns to his iconic role alongside such fresh faces as David Ellison, the movie-loving billionaire’s son; Apollo Global Management’s Marc Rowan, the kinder, gently private equity CEO; Bratz producer Stephen Paul; and in a surprise bit of casting, Canadian whiskey scion Edgar Bronfman, Jr, better known for his own role in the '90s Universal drama, in which he shared some memorable scenes with Diller.

Of course, if Diller is known for anything in the last 30 years, it’s . . . running America’s fourth-favorite search engine? No, that’s not it. (If you have to ask, that’s Ask.com.) Incubating Tinder? Impressive in its way (and lucrative), but no.

Ah yes: Talking smack about Hollywood at every opportunity.

Over the years, Diller has been one of the staunchest critics of Hollywood — and the movie business, in particular — for, well, everything. You don’t have to believe me: You just need to read Diller’s own words (and in some instances that of his confidants) going back even earlier than his efforts to buy Paramount in 1994, which I’ve compiled below.

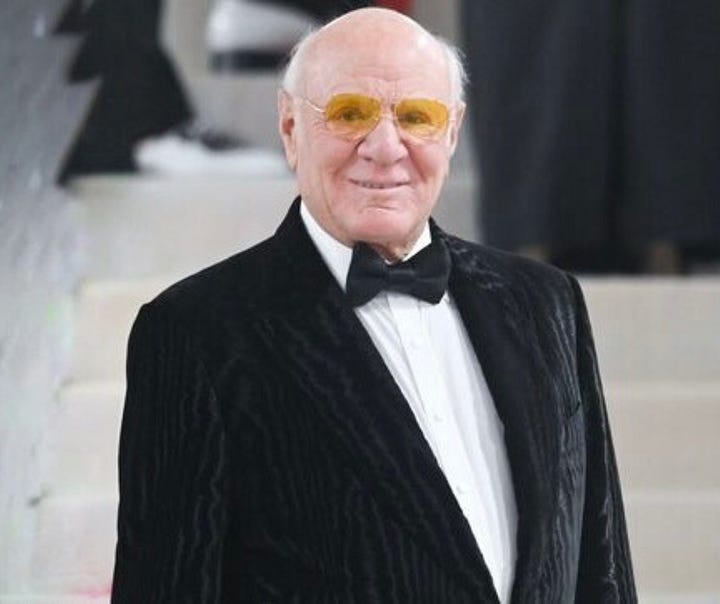

There literally are 40 years of Diller quotes speaking ill of Hollywood and how it operates. It all makes one wonder what Diller, 82, sees in Paramount today.

So I asked him.

By email, Diller responded to me today when asked about his past comments and his potential interest in Paramount:

“I have no comment on rumors or speculation. On ‘hollywood’ [sic] however, what I’ve said is that its hegemony over entertainment has ended, that given their resources the tech overlords will control its future, but I never said that the legacy studios couldn’t thrive in that future — on the contrary I’ve always said they can.”

With Sun Valley — the annual “summer camp for billionaires” — in just one week, Diller certainly may say more, and is sure to be a center of attention (and perhaps that’s its own reward?).

So, have a gander at Diller’s own words. Does this sound like a guy who wants to own a movie studio? Or does he protest too much — and therefore sounds exactly like a guy who should?

2023: ‘Too Old,’ ‘Truly Finished’

When Diller attended the Semafor Media Summit in April 2023, he was mostly there to advocate for his (ultimately failed) bid for publishers to band together against AI. But, inevitably, he was asked about Hollywood.

“At its best, that kind of editorship, which is what running those [entertainment] companies are, it’s making choices between this film or that film, or this project or that project,” he told Semafor cofounder and editor-in-chief Ben Smith. “Experience is not the great helper here because usually, your instincts over time get cynical and corroded. If you want to take risks, and if you don’t want to take risk creatively, you’re not going to have much. I think it’s all become too old and too suited,” said Diller, 81 at the time and wearing a suit.

Just two months earlier, Diller, appeared on PBS’ Firing Line with host Margaret Hoover, where he was somehow coaxed to share his feelings:

“No one is going to compete with Netflix. I believe they have won the game. And I think that there’s nothing that I can see that’s going to dislodge them.

“And then along comes the pandemic, and that increases the shift because people stay home more, etc., etc. So there are more subscriptions, etc. The entire movie business crashes because there’s no movie theaters, because people can’t go to the theaters. And that whole infrastructure of — the hegemony, let’s call it, of Hollywood, which had ruled for 75, 80 years, it only took three or four years for it to totally disappear. Totally disappear in the sense that it’s over. There is no hegemony anymore of those, let’s call it those major motion picture companies. It’s truly finished. It is never coming back.

“There really is no movie business anymore. It doesn’t exist. The whole motion picture role of, let’s say, Hollywood producing about 125 movies a year, rolling them out theatrically, that’s over.”

2021: ‘Almost Zero’ Interest in the Movie Business

“The movie business is over,” Diller said in an exclusive interview with NPR from the annual Allen & Company Sun Valley Conference. “The movie business as before is finished and will never come back.”

“There used to be a whole run-up,” Diller said, referring to the kind of publicity campaigns that Paramount was renown for in the 1980s when he ran the studio. “That’s finished.”

“These streaming services have been making something that they call ‘movies’,” he said. “They ain’t movies. They are some weird algorithmic process that has created things that last 100 minutes or so.” (Well, Diller’s not totally off base there, as Entertainment Strategy Guy explored streaming’s litany of spring flops last week.)

The very definition of what a “movie” is, he told public radio, “is in such transition that it doesn’t mean anything right now.”

He went on to add that he had “almost zero” interest in the modern movie business, preferring producing Broadway plays such as To Kill a Mockingbird and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolff, both of which were, of course, iconic films. “I find that far more creative.”

Two weeks later, Diller had to clean up his comments a bit with a follow-up interview with L.A. public-radio station KCRW, saying that, in fact, the movie business was not “over,” but “because of streaming, because of the pandemic, because of the enormous production of long-form content . . . what we think of as a movie is evolving, and no longer means what it did just a couple of years ago.”

By “evolving,” Diller specified that he meant only that the business’ dynamics will continue “to vague out what that term ‘Hollywood’ or ‘movies’ represents,” and that only 10 percent of theaters worldwide would be left in a few years.

The result? “The irrelevance of ‘Hollywood, because it does not exist anymore.” The Hollywood that could create “one-off assets” that could stand on their own against the “‘Bond’ series, or Star Wars, or anything” hasn’t been around for some time, and “the ability to do that has been forever compromised.”

“That's significant,” Diller said. “All of the big returns have been made by these big, sequelized blockbusters that roll out every two or three years that are capitalized at $300 or $400 million, and that return over $1 billion.”

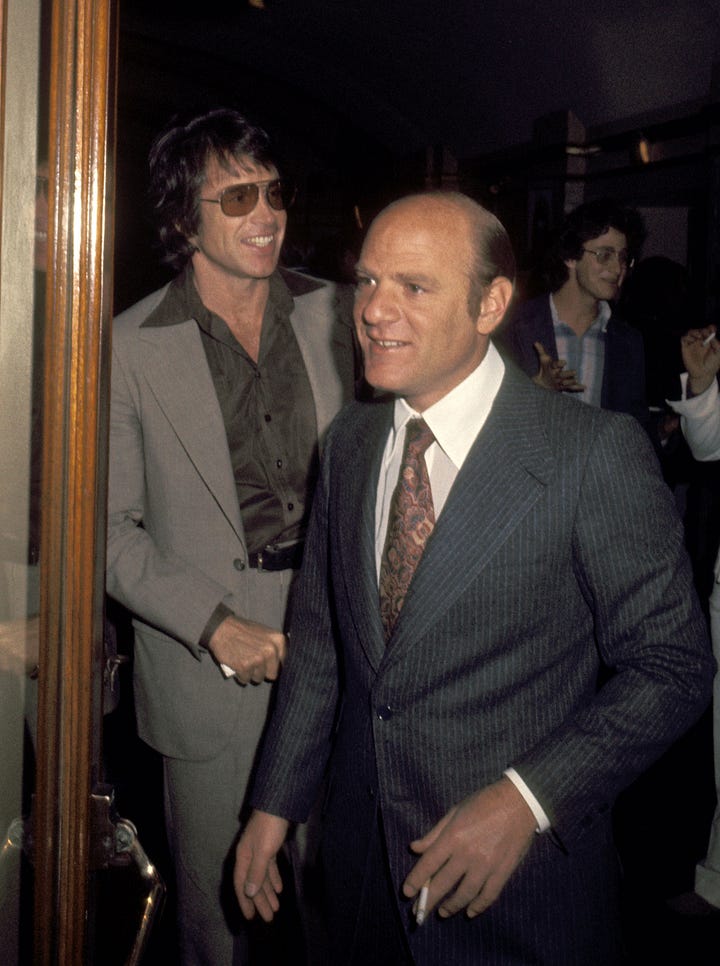

Under Diller’s leadership of Paramount as its chairman from 1974-84, the studio made such movies as Grease, Reds, 48 Hrs and Flashdance. Today, let’s see what Diller’s big plans are for Transformers!

2019: ‘Irrelevant’

Over, done, finito. If there’s a way to refer to Hollywood’s demise, Barry Diller has probably said it.

His turn of phrase in 2019: “Irrelevant.”

“Hollywood is now irrelevant,” Diller said on tech journalist Kara Swisher’s podcast at the time. “These six movie companies essentially were able to extend their hegemony into everything else. It didn’t matter that they started it. When it got big enough, they got to buy it. For the first time, they ain’t buying anything. Meaning they’re not buying Netflix. They are not buying Amazon.

“In other words, it used to be if you could get your hands on a movie studio, you were sitting at a table with only five other people,” he added. “And so that table dominated media worldwide. That’s over.”

But wait — there’s still more!

2018: Running a ‘Horse-and-Buggy Company’

In 2018, before he was calling most movies “long-form projects,” Diller was already convinced that “the idea of a movie is losing its meaning.” So what would be the point of running a movie studio, then?

“It would be like saying, do I want to own a horse-and-buggy company?”

When Diller entered the movie business at Paramount in the 1970s, he told fellow billionaire Reid Hoffman in 2018, “there’s seven movie companies, Paramount was number seven—made horrible movies, everything was awful.”

Diller noted that he was the “first person from television to come into the movie business. In later years, one by one by one by one, almost everybody came from television. Because television was, first of all, the more creative medium, interestingly enough. And had much more actual story discipline in certain interesting ways than the tired, old hoary movie business.”

2017: ‘Hardly a Great Business Proposition’

“Movie companies rarely make a lot of money,” Diller said during a keynote session at the 2017 CES trade show in Las Vegas. “A standalone movie studio today is a hardly a great business proposition,” he said, noting Disney as an exception.

Movie studios, he lamented, are centered around “huge, blockbuster movies that have to do $500 million to break even — I mean, that is not a creative enterprise. The fact we get any good movies is almost a miracle.”

2016: ‘Enormous Challenges’

After a long hiatus weighing in on the state of Hollywood (as you can see below, the next entry is 2001), this Politico interview appears to be the kickoff for Diller’s current run of media doomsaying.

Diller, in full media futurist mode, opined on how the internet has “broken the control of media by the few.” The upshot of all that fragmentation? “Enormous challenges . . . and over time I think . . . the descending value of large media enterprises.”

Certainly true about Paramount!

2001: ‘Disenchanted,’ ‘A Terrible Business’

In 2001, Universal Studios — where Diller was slated to take the reins after French media conglomerate Vivendi had acquired Seagram— had two deals that paid production companies hundreds of millions of dollars to make films without much input. One was with Brian Grazer and Ron Howard’s Imagine Entertainment, and the other was with British production outfit Working Title.

Studios were beginning to give the go-ahead on those types of talent and production company-friendly deals, and Diller loathed the new (and soon to be widely common) deal structures, which reduced studios’ leverage while also costing them enormously.

“Over the years Barry became more and more disenchanted with the movie business — the economic margins were shrinking and shrinking and the egos were getting bigger and bigger,” Leonard Goldberg, a top producer and former studio chief and a longtime friend of Diller told the New York Times. “It became harder for him to justify the way the business was going.”

Not to mention how he felt about TV: “Barry’s feeling about television is it's a terrible business,” said one person who had spoken with Diller shortly before the article’s publication. “You spend all this money on development, you hire producers and writers, you take all the risks and the odds are slim that you'll make back any money, especially if you give pieces of the show to the talent.”

1990s: ‘Turning the Titanic’

In 1998, when Diller was the chairman of the USA Networks, he entered into a strategic partnership with Bronfman-led Seagram, which owned Universal Studios. The deal integrated Universal’s film and television assets with Diller’s broadcast and cable television assets. The move was said to have “re-energized” Diller, according to one of his associates.

But not because of the film assets, Diller acknowledged: “Television is the one medium that you can turn on a dime, whereas in the movie business, as well as the retailing business, to turn the ship is like turning the Titanic,” he said.

But Diller had a plan — one that might not seem so exciting to anyone working at Paramount today. At the time, despite USA Networks’ new ownership of the Universal Studios television production business, Diller said he planned to keep most of the shows local.

“It's too expensive in Hollywood,” he said.

Six years earlier, upon leaving Fox, Diller believed much the same: “In recent months, Diller has expressed distress at the high cost of making and marketing movies,” the L.A. Times wrote in 1992.

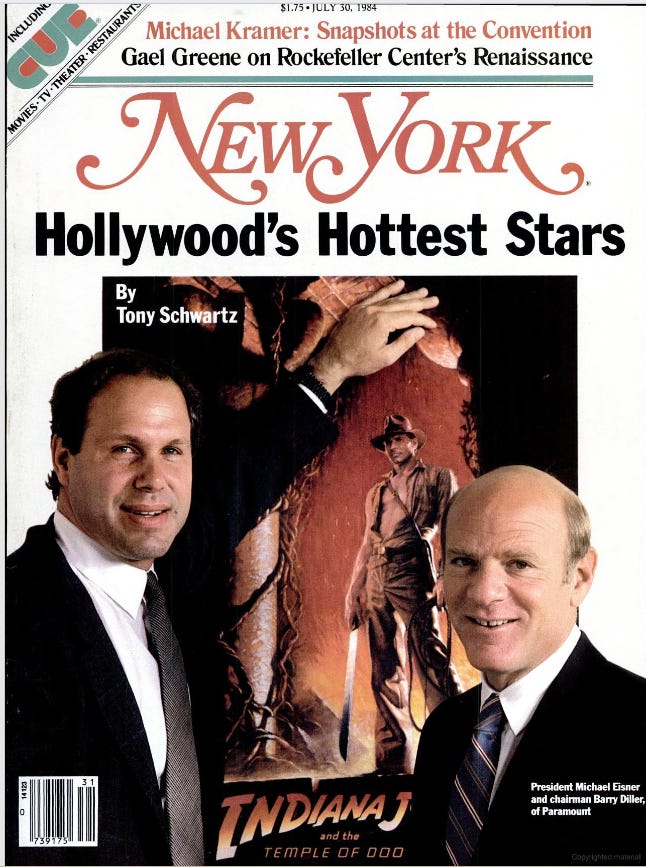

1984: Early Troubles

This 1984 magazine feature on Diller when he served as chairman of Paramount in the 1980s leads one to ponder if he ever loved the movie business. The company was a paragon of stability, the envy of Hollywood for its marketing and distribution, it was the home of Eddie Murphy and James L. Brooks and it had made such acclaimed films as Ordinary People and An Officer And A Gentleman.

Yet Diller’s lack of enthusiasm was palpable.

He “took a while to find himself at Paramount,” according to New York writer Tony Schwartz. “You can’t imagine how miserable I was,” Diller said of his first year in the job. “I was used to action and quick reaction. Here, nothing seemed to happen.”

His faith turned around, though, with just one script he found in a drawer. It had three acts. A crummy team that “gets better, falls apart, and then prevails.” Diller said, “My God, a story.” He bought the script in 22 minutes.

“It was the first time that it seemed possible things might just work out,” he said.

That script: The Bad News Bears.

Diller might as well be Morris Buttermaker (Walter Matthau) coming in to coach Paramount back to relevance. Maybe Paramount’s team of misfits — its movie studio, broadcast network, cable channels, streaming offering — can amount to as much as the Bears did.

Or maybe, like Matthau’s dramatic monologue to Tatum O’Neal, Diller’s saying what he’s been saying for decades: “Goddamn it! Can’t you get it through your thick head I don’t want your company?”