Al Pacino and the Real-Life Bank Robbery That Changed Everything

Exclusive excerpts from the actor's new memoir, ‘Sonny Boy’, reveal how his role in 'Dog Day Afternoon' was a turning point — and humanized a trans romance

Joe Pompeo writes about Hollywood history every other Saturday. He previously revisited the lurid tabloid deaths of Marilyn Monroe and Rudolph Valentino. He can be reached at joepompeo@substack.com, and has a personal Substack. Today, Joe utilizes exclusive excerpts from Al Pacino’s forthcoming memoir, Sonny Boy (Oct. 15) to inform his mid-1970s recounting of Pacino’s career crossroads, when one of the hottest actors flirted with leaving the business — until an irresistible true crime changed his mind.

One day in . . . oh, it must have been early 1974, Al Pacino was staring at the purple curtains in his sixth-floor luxury hotel suite in London, overlooking St. James Park. He watched a mouse climb the fabric, only to be attacked by a bat that swooped in out of nowhere. Was he seeing things? Dreaming? Pacino had a history of delirium tremens, which perhaps explained the strange visions before him. As he gazed hypnotically, it was as if he could see his old friend and mentor Charlie Laughton, seated at the opposite end of a long table with a large bottle of hard liquor by his side.

Pacino, entering his mid-30s and fresh off his second portrayal of Michael Corleone, had already made a name for himself as a breakout Hollywood star of the disco era. Following the success of the first two Godfather films and Serpico — all within two years — Pacino’s manager, Marty Bregman, had found yet another gritty drama for his ascendant client.

But Pacino, whose career began in the theater, wasn’t into it. He’d had enough of waving a gun around and committing fictional crimes on screen. Not only did he want nothing to do with this next picture Bregman had lined up, but maybe he wanted to get out of the picture business altogether.

Pacino explained all of this during his imagined conversation with Laughton in the London hotel room.

“I know, Al,” said Laughton. “What do we do next?”

“What I’m going to do is not do this film,” Pacino replied. “That’s what I’m going to be doing.”

14 Twisty Hours in Brooklyn

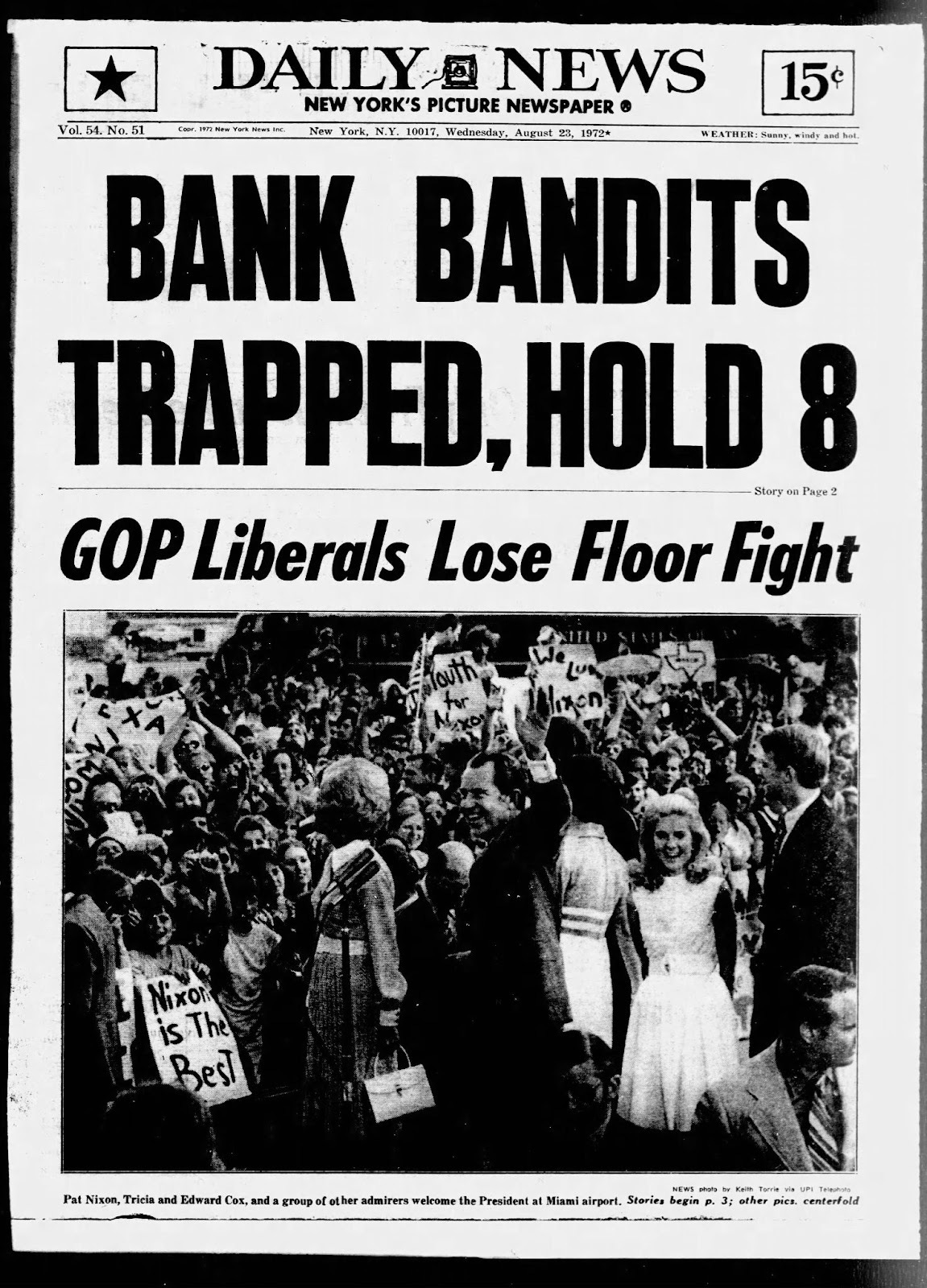

A couple years earlier, on a Tuesday, Aug. 22, 1972, around 3 o’clock and just before closing time at a Chase bank on the corner of Avenue P and East Third Street in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, a baby-faced young man named Sal Naturile sat down at the branch manager’s desk and said, “Freeze. This is a holdup. I’m not alone.”

What transpired from there was a plotline made for the movies: Over the next 14 or so hours, Naturile and an accomplice, John Wojtowicz — himself a former bank teller — held the branch manager hostage along with seven female employees. More than a hundred patrol officers, detectives, and members of the FBI surrounded the joint, crouching behind cars as police snipers aimed their weapons from the rooftops of adjacent buildings.

In the midst of the standoff, reporters called into the bank and spoke with Wojtowicz, who vowed to kill the hostages if any police came storming in.

“We got information from a man downtown — an employee in the bank’s main branch — that we could get between $100,000 and $200,000 in this branch if we hit it at five-to-3 today,” Wojtowicz told a Daily News reporter. (That’s between $750k and $1.5 million in 2024 dollars.) “We waited while the customers all came out. The last one was a lady carrying a baby. Then we pulled out our guns and stuck up the place. We got $29,000.” (More than $200,000 today.)

Wojtowicz explained that they were about to make a run for it when a cop car pulled up out front. “Everything would have been alright if they had come a couple minutes later.” (A third conspirator, Robert Westenberg, managed to get away.)

The interview took an unexpected turn.

“I’m a homosexual,” said Wojtowicz. “I told the cops to get my wife — he’s a male, his name is Ernest Aron — from King’s County Hospital . . . I was supposed to pick him up today. I told them if they bring him here I’ll release half the hostages out the back door. Then we’ll negotiate. What the hell have they got to lose? We know they’ll catch us eventually, but we’ll stop and talk and maybe release a few hostages at a time until we get where we’re going.”

Which would be . . . ?

“I won’t tell you where. When we get there, the cops can kill us then. I’m not afraid to die . . . If they fire a shot, we’ll return it and everybody will be dead.”

Luckily it didn’t come to that. The police made good on their word and brought Aron, a psychiatric patient, to the bank. He spoke with Wojtowicz at the front door and again by phone. The life-threatening spectacle also included visits to the crime scene from “homosexual friends of the gunmen,” in the words of the then-homophobic New York Times, “who kissed them in the bank doorway to the cheers of the huge crowd.”

Wojtowicz demanded transportation to Kennedy International and a plane out of the country to points unknown, where the remaining hostages would be released. At 4:45 a.m., the hostages and their captors got into an airport limousine driven by an FBI agent. When the car arrived at the designated runway, the fast-thinking lawman whipped out a .38 he’d concealed under the floor mat and shot Naturile in the chest, killing him. Wojtowicz surrendered without incident, and the hostages scurried to freedom on the tarmac.

As it turned out, Wojtowicz had acted out of desperation. (His co-conspirators? Not so much.) He was estranged from his real wife and “married” to his aforementioned “wife” Ernest Aron (the wedding wasn’t legally binding), who was in fact a transgender woman who’d attempted suicide because she couldn’t afford sex reassignment surgery. “Love is a very strange thing,” Wojtowicz would tell a federal judge. “Some people feel it more deeply than others. I loved my wife, Carmen. I love my son, my daughter, my mother, and I love Ernie. Ernie is very, very important to me and I’d do anything to save him.”

'Tell it the Way it Happened'

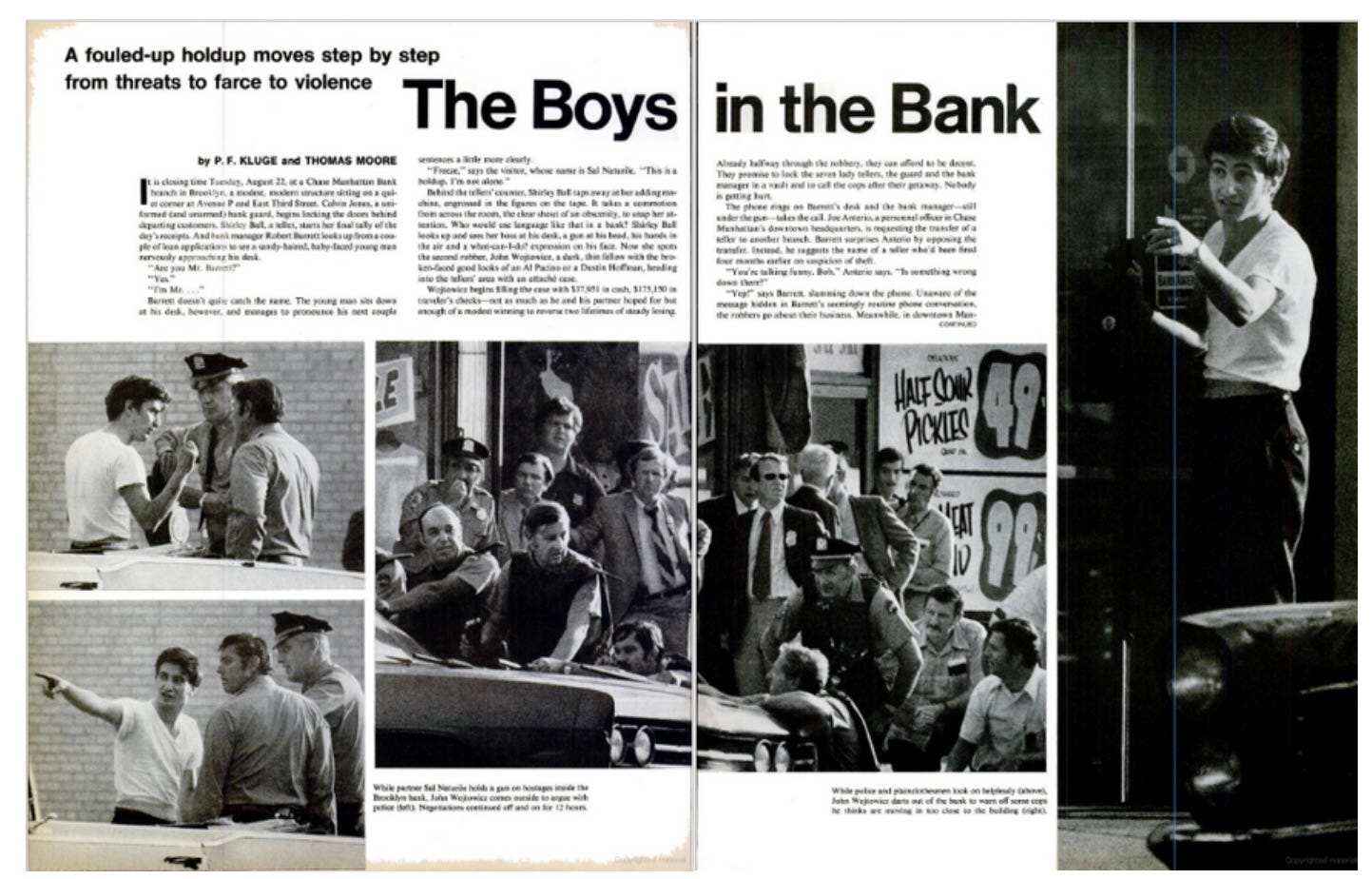

A month later, on Sept. 22, 1972, Life magazine published a riveting reconstruction of the episode. In the opening scene of the feature, headlined “The Boys in the Bank,” a teller named Shirley Ball watches Wojtowicz enter the Chase branch holding an attaché case. In the moment, Wojtowicz’s “broken-faced good looks” remind her of Al Pacino.

“Wojtowicz begins filling the case with . . . cash,” wrote the journalists P.F. Kluge and Thomas Moore, “not as much as he and his partner hoped for but enough of a modest winning to reverse two lifetimes of steady losing.”

As the authors noted, “There was nothing in John Wojtowicz’s early years to suggest that he would ever find himself holding off police at the doors of a bank and haggling with them for a meeting with a homosexual spouse. For most of his 27 years his life seemed pointed to nothing more than a routine job, a faithful female wife, and someday a move to the suburbs.”

Among those captivated by the Life piece was a burgeoning producer named Martin Elfand. He brought the article to the attention of Bregman, who could smell the Hollywood catnip as he negotiated a deal with Warner Bros. He and Elfand went about securing releases from everyone who would be portrayed in the film. As Bregman later recalled, “They all had to be convinced that we would tell it pretty much the way it happened.”

The hostages, save for one holdout, got $600 each from the filmmakers (about $4,500 today). Westenberg, after initially turning down a $2,000 offer, settled for $750. Wojtowicz, serving out a 20-year sentence, agreed to $7,500 for the motion picture rights to his story. He gave $2,500 to his beloved Ernie, who used the money to become Elizabeth Eden. (As for the late Sal Naturile, Warner Bros. footed the bill for a burial next to his father’s grave in Elizabeth, N.J.)

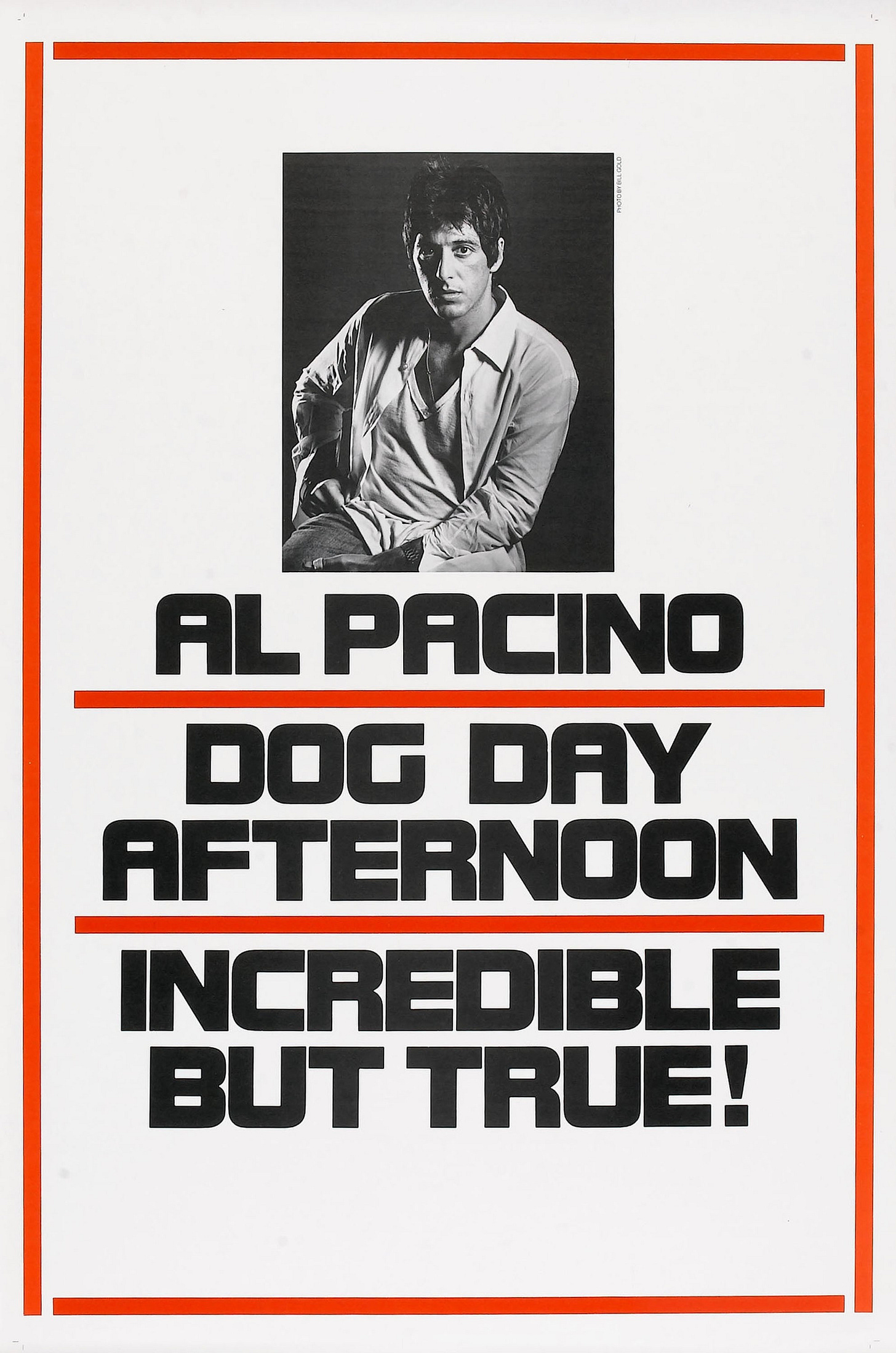

With a finished script for a movie called Dog Day Afternoon and Sidney Lumet locked down as the director, Bregman now had to convince Pacino to accept the starring role as John Wojtowicz, whose name would be changed to Sonny in the film.

'Do It For Me'

“I went back to New York,” Pacino writes in Sonny Boy, “having passed on the project, when I got a call from Bregman at a very opportune time. He wisely waited until he knew I wasn’t drinking, and he asked me if I would read Dog Day Afternoon again.”

Pacino’s heels were dug in, but Bregman persisted.

“Why don’t you give it a read for me?” he pleaded. “Do it for me. I really need you to read it.”

Pacino, who was living in Candice Bergen’s former apartment on the Upper East Side, reluctantly agreed. Reading the script with fresh eyes, Pacino found himself utterly hooked. He called Bregman back right away.

“Why am I not doing this film?” he said.

“That’s all I wanted to hear,” Bregman replied.

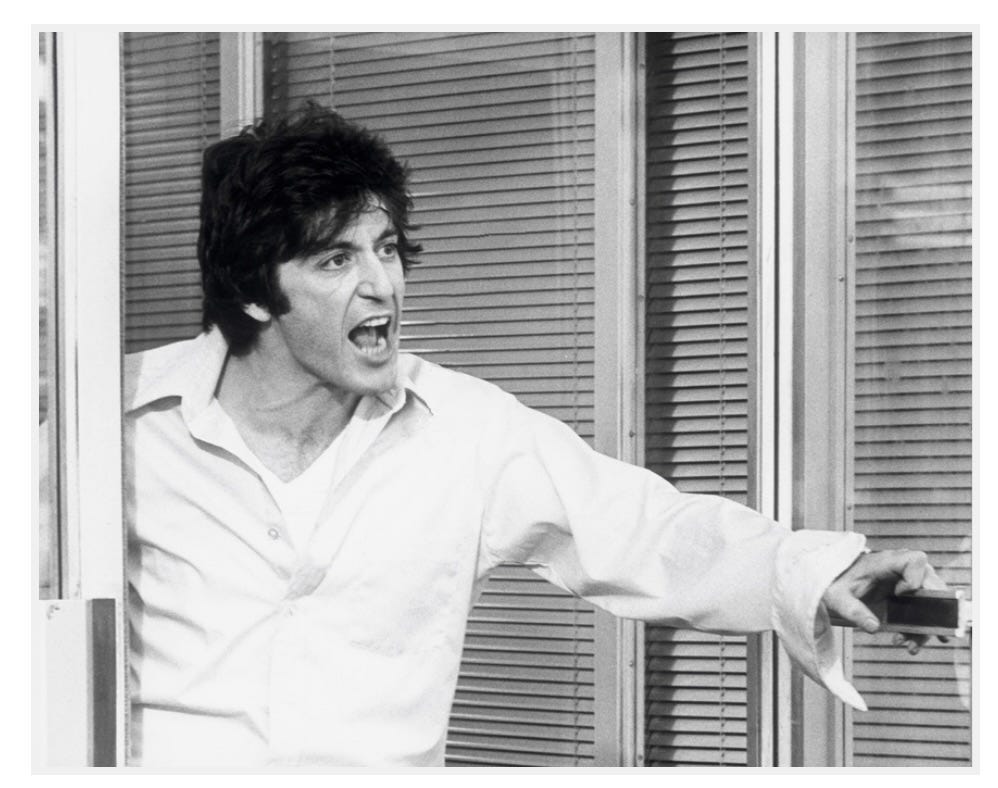

In Sonny Boy, Pacino reflects on playing a character with a “complex” sexuality during a less enlightened era.

“Knowing this about him didn’t excite me or bother me; it didn’t make the role seem any more appealing or risky,” he writes. “Perhaps at the time of Dog Day Afternoon it was an uncommon thing to have a main character in a Hollywood movie who was gay or queer, and who was treated as heroic or worthy of an audience’s affection — even if he did rob banks. But you have to understand that none of that enters into my consideration.”

Still, one element of the script really bothered him. In the original version of the scene that portrays Leon (Aron) being brought to the bank to speak with Sonny (Wojtowicz), Leon arrives dressed as Marilyn Monroe and the two kiss outside in front of the assembled hordes. Pacino found this dramatic embellishment to be a bit ridiculous and, worse, minimizing. He argued about it with Bregman and Lumet.

“We are dealing with human beings, whether they are heterosexual or homosexual,” he recalls barking at the filmmakers.

Lumet stood down, allowing Pacino and Chris Sarandon, who’d been cast as Leon, to improv the dialogue as if speaking by phone, which is how the scene went down in real life.

“That is Lumet magic,” Pacino recalls. “We did three separate takes of improvisations and then Lumet cut and pasted them together with me and Chris to create the scene.”

‘Attica! Attica!’

For Pacino, the most powerful moment of Dog Day Afternoon happened spontaneously. He was about to film a scene where Sonny steps out to address the crowd. As Pacino walked outside the bank, assistant director Burtt Harris whispered, “Say ‘Attica,’” referring to the upstate New York prison that had endured a brutal riot months earlier.

“So I got out on the street, and I was talking to the crowd. All of a sudden, I say, ‘Remember Attica?’ And the people started going fucking crazy. And I thought to myself, That’s what film can be. Go out there, go for it. Something may happen.”

Dog Day Afternoon premiered in New York on Sept. 21, 1975, ahead of a nationwide release the following month. It was a commercial and critical success, grossing more than $50 million at the domestic box office (almost $300 million today) and earning raves in the press.

In a four-star review, Gene Siskel called it a “superb new movie . . . full of unbelievable scenes . . . about behavior that deviates from the norm.” His praise for the film’s leading man was similarly effusive: “As for Pacino, he displays so much energy he actually reverses one of the rules of the cinema . . . [T]hat just because an action in a movie is based on a true incident doesn’t make that action believable on screen.”

Among Pacino’s canonical roles, Dog Day Afternoon doesn’t have the iconic name recognition of The Godfather, Serpico or Scarface. But for a movie that its star almost refused to do — at a moment when he was on the verge of reconsidering his career — it represents a pivotal moment in Pacino’s development as an actor.

“My fame was not just bigger after Dog Day,” he writes in Sonny Boy, “but more intense. That will happen sometimes to certain people, for reasons that have to do with circumstance and timing, the doors opening and closing. The time just happened to be right for someone like me.”

Frank Pierson? Academy Award?

“Ernest Aron was escorted to the crime scene wearing her hospital gown”

Her? Hadn’t transitioned when the photo was taken.