'Afraid': ICE Raids Shake Hollywood’s Immigrant Workforce

Productions disrupted, workers paralyzed: Crew & staff who grew up undocumented (like I did) are filled with fear as studios stay mum

I write about TV from L.A. I interviewed a top agent-turned-manager about his take on the TV marketplace, reported on the boom in microdramas and wrote about how L.A. sound stages are scrambling as SoCal production dwindles. Reach me at elaine@theankler.com

Hello, Series Business readers: With everything going on in the world, I wouldn’t blame you if you were having trouble focusing on — checks notes — making TV shows right now.

Abroad, there are very loud overtures of war. Here in Los Angeles, immigration raids have upended daily life for many, with entire parts of the city paralyzed as federal agents swarm local businesses in search of undocumented immigrants: bus ridership has plunged, stores have closed, and childcare providers are bracing themselves for visits from ICE.

Then again, perhaps the news cycle isn’t deterring you too much. After all, it’s easier to keep your head down and pay attention to the things you can affect rather than the seemingly endless turmoil that envelops the world around us. Fair enough.

But it would be a mistake to think that what is happening on the ground in L.A., distant though it may feel from most Hollywood offices and backlots, is completely detached from the entertainment industry.

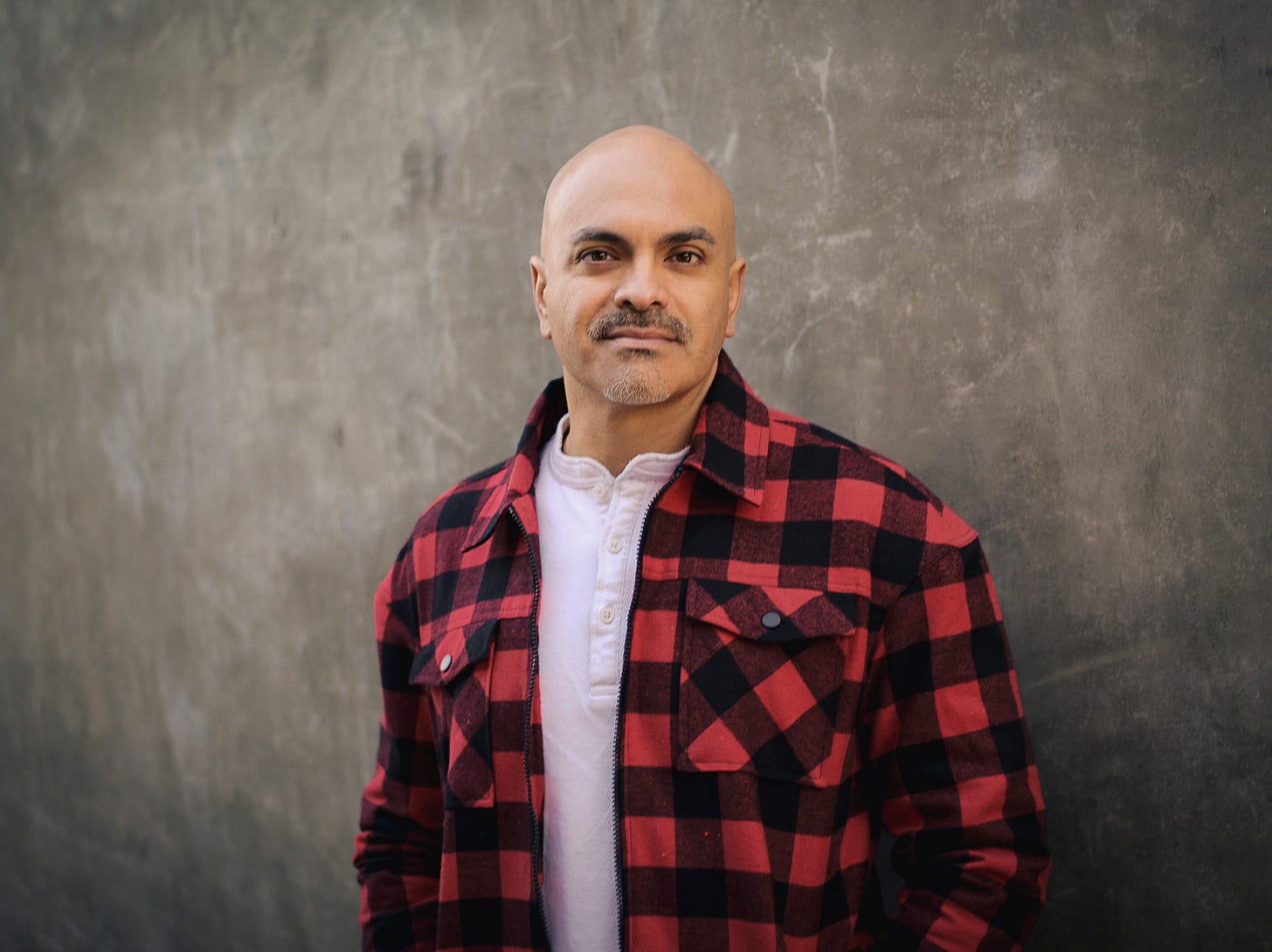

“You can’t sit in a Hollywood office that was most likely engineered, built and maintained by immigrants and think this issue doesn’t affect you,” says Rafael Agustín, a TV writer best known for his work on several seasons of Jane the Virgin — and who was once an undocumented immigrant himself.

At the studios and on set, it’s unlikely that there are undocumented workers — strict employee verification processes make sure of that — but there are still plenty of people working legally in the industry who are afraid of being wrongly swept up in the raids.

Case in point: Laborers International Union of North America (LiUNA!) Local 724 represents about 1,800 utility workers who support carpenters, plasterers, painters, electricians and other TV and film craftspeople, as well as workers at Universal Studios Hollywood and janitorial staff at the major studios — the people who take care of your workspaces when you go home for the day and literally build the sets where your shows are filmed.

Local 724 business manager and principal officer Alex Aguilar, Jr. tells me he’s gotten phone calls from members who are scared, despite being legally in the U.S. About 20 percent of LiUNA members are immigrants, he estimates, and around half are Latino.

“I asked them, ‘Hey, is everything okay? How are you doing?’” recounts Aguilar. “They’re like, ‘Well, we’re afraid to come to work, because now they’re just picking up anybody, right?’” The perception is that law enforcement believes “if you’re brown and you have an accent, then you’re here illegally.’” Recent news reports of legal residents and U.S. citizens getting caught up in immigration nets, sometimes violently, have stoked those fears.

Hollywood, like most American industries, was built on the backs of immigrants. Some just happened to grow up undocumented, like Agustín, who spent his childhood in the San Gabriel Valley obsessed with B-movies like the Michael Dudikoff starrer American Ninja, or Aguilar, who worked for years as a laborer on the sets of feature films — and even, say, an entertainment business reporter like myself.

Some kids learn the unpleasant truth when they apply for a driver’s license or fill out college applications. My parents and I moved from Singapore to Chicago when I was 11, and I always knew that I was undocumented. It becomes a defining part of your being, weaving its way into your personality: Keep your head down, follow the rules, stay out of trouble, work hard. There is no room for teenage rebellion or youthful detours when you can’t even jaywalk without fearing deportation, and it is distinctly jarring to come of age feeling American while knowing that you don’t technically belong.

After high school, my friends went to places like Yale and the University of Chicago. I got into Northwestern but couldn’t afford it without financial aid; instead I earned a full scholarship from a local university that didn’t care about my status, which is fortunate, because I wouldn’t have even been able to afford community college without it. I was the first in my immediate family to go to college at all.

While my friends spent their early 20s going to grad school and finding their first full-time jobs, I spent it hustling for freelance work — tutoring, writing one-off stories and working the booths at conventions like E3. I’d go to the local sliding-scale clinic and see student dentists because I didn’t have health insurance. And I always, always made sure to pay taxes on whatever paltry amount I brought in. You won’t find anyone scrappier or more patriotic than a young undocumented American.

So in this week’s Series Business, let’s talk about:

Which productions in L.A. have been disrupted by raids and protests

How the guilds are responding to the turmoil

Why legal immigrant Hollywood workers are fearful of heading to job sites

The personal pain, shame and anxiety of growing up undocumented in the U.S.

How Agustín found his way to Hollywood, and the story he’s still hoping to tell as a TV writer

How Aguilar is guiding guild members through an anxious time

The invisible and integral work immigrants do in the entertainment industry, on and off the set

Raids, Protests, Production Disrupted

For now, it’s mostly business as usual in Hollywood, though the turmoil is spilling over into local productions. For about a week in mid-June, downtown L.A. was saddled with a curfew order that meant that all filming in the area had to end by 8 p.m. and start no earlier than 6 a.m. The curfew was lifted on June 17.

FilmLA tells me there have been 50 locations with permits to film downtown since June 9, the Monday after the raids began, including a number of commercials (Progressive, Toyota), online content (GQ, Entertainment Weekly), a few shorts and features, and seven TV series, from Netflix’s The Lincoln Lawyer to Peacock’s House of Villains. Most of the guilds tell me they haven’t registered any change in activity related to the ICE raids (SAG-AFTRA) or have declined to comment (IATSE). With fewer and fewer projects filming locally in Los Angeles, the impact on production hasn’t been as dramatic as it might have been even a few years ago.

But a source close to The Lincoln Lawyer, which films in downtown L.A., tells me that production was “definitely disrupted somewhat,” first by the protests against the raids, then by the National Guard and local law enforcement swooping in to quell them. On the first night of the protests, the Netflix series was filming across the river in East L.A. and was interrupted by “multiple very loud news helicopters circling above us all night.” Several scenes had to either be postponed or filmed in alternate locations at the last minute, I’m told, although filming was not forced to shut down.

A Winding Path to Hollywood

In pitch rooms, immigrant narratives have been a tough sell for TV writers. Agustín tells me that he’s clocked a fear of buying such stories, including a small-screen adaptation of his published memoir about growing up undocumented, Illegally Yours.

“No one wants to buy this right now, obviously because of the Trump administration,” he says. “He has put the fear of God into buyers, and that’s sad.”

Agustín was only 7 when his family moved to the U.S. from Ecuador. His father, a pediatric surgeon, and his mother, an anesthesiologist, fled political and economic turmoil in their home country in search of stability. Starting over here undocumented while learning a new language meant giving up their medical careers; his father worked at a car wash and his mother found a job at Kmart.

Having overstayed their tourist visa, they shielded their son from the reality of their situation for years. Agustín grew up steeped in American pop culture, watching Spanish-dubbed reruns of Adam West’s Batman and being elected class president. It wasn’t until he applied for a driver's license in high school that he learned that he was not technically American.

Agustín worked under the table at a video store as a teen, lying about his age to get the job, which would ultimately fund his community college tuition. While he was in college, his parents’ application for permanent residency — a green card — that they had submitted nearly 15 years prior, while still in Ecuador, was finally approved.

After his status was adjusted, Agustín went on to attend UCLA, receiving financial aid and earning a bachelor’s and master’s degree, before writing a comedy show that received national acclaim. That led him to meet Gina Rodriguez and Jennie Snyder Urman and land a spot as a writer on The CW’s Jane the Virgin, where he stayed for two seasons.

He has recently found a showrunner with “commercial comedic sensibilities” who is taking on the adaptation of his memoir, and they think they have found a way to bring the show to a broader audience. While he is developing several projects right now, “That’s the one I’m most excited about, because I finally get to bring an undocumented family to television, which I’ve been wanting to do for a while,” Agustín says.

Protecting ‘Hard-Working’ Hollywood Labor

LiUNA’s Aguilar, like Agustín, moved to the U.S. with his parents when he was just a kid — at 8 years old with two younger sisters, from Mexico City. His father toiled at a car wash and his mother worked as a housekeeper in Los Angeles; after work, his parents would come home to make dinner for the kids, then head out to their night jobs, doing custodial work in commercial buildings.

His journey into the industry was much different from Agustín’s. Aguilar’s mother worked for an SVP at a major studio, cleaning his massive house in Encino. One day, the studio exec got worked up about the state of his car collection, which he felt wasn’t being detailed properly. (Hollywood problems!) Aguilar’s mother recommended her husband, who then detailed the exec’s cars to satisfaction before asking for a job at the studio. Aguilar Sr. went on to work as a laborer on set, “and the rest is history,” says Aguilar, who followed in his father’s footsteps and got into studio work as a laborer shortly after high school.

The current raids pain Aguilar because he remembers what it was like growing up in fear, trying to stay out of trouble.

“These people are hard-working people, just like my mom and dad, not causing any problems, just going to work, hoping to make it home and go back the next day and do it all over again,” he tells me. “The fact that that’s not even keeping them out of it is heartbreaking.”

Aguilar was 18 when he was finally able to adjust his status and become a permanent resident. Thanks to the Reagan-era Amnesty Act of 1986, which allowed around three million employed undocumented immigrants to become legal residents, Aguilar’s father was able to apply for a green card through his boss at the car wash.

“An Iranian man helped my father file for his paperwork so that we could have a better shot at life,” notes Aguilar pointedly, in a nod to current events. “It was Tony from Iran who helped my family.”

Since 2011, the 48-year-old Aguilar has been working full time at LiUNA — where his father is now an executive board member — and has in the past week fielded calls from worried Local 724 members who are on work permits or who live in mixed-status households with undocumented spouses. None of the members he reached out to would speak to me for this story, even anonymously, underscoring the fear bred by this climate.

‘Most of Us Are Here Just for a Better Shot’

Both Agustín and Aguilar have long since become naturalized citizens — as have I, thankfully — but it’s not hard to remember the terror and uncertainty that comes with being undocumented. More than a decade after adjusting my status, even after co-creating a web series about my experience that won an award at the 2014 New York Television Festival, I’ve only in recent years gotten more comfortable talking about it publicly. (I still refuse to jaywalk.)

There’s a massive sense of guilt and shame that comes with growing up this way, one that some people overcome — see Agustín’s memoir — and can cause others to shrink away from the limelight.

LiUNA’s Aguilar does not feel comfortable dredging it all up, and neither do I. We both get a little choked up over the course of our 45-minute conversation simply recounting personal histories. It’s weird and tough to talk about this in the context of the business. But what’s happening in this city has hit close to home.

In a recent business meeting with other industry folk where the topic of the raids came up, Aguilar says a union rep told him, “Well the good thing is, this doesn’t really affect you, right? You were born in this country… You speak English properly.” Aguilar corrected him on the spot.

“I haven't been crazy vocal or anything like that, because I also don't want people to think that we're here trying to cause problems,” he tells me. “I'm an immigrant, and most of us are here just for a better shot at life and to get ahead for their kids, for their families.”

But it feels important for him to say something now. For so many immigrants, regardless of legal status, this is personal. The members of Local 724 are largely unseen and unrecognized by the greater Hollywood community but are a workforce integral to giving the industry its gloss of glamour.

“Sometimes the CEOs come to the studios, and our folks do all the landscape and tree trimming and cleaning the streets of the studio,” says Aguilar. “The appearance of the studio, when a CEO walks in or drives in, and everything's well manicured and the stairwells are clean and there are no cobwebs everywhere, and even the lights in the parking structure [are] dusted — we do all that. We literally do all of that to make sure everything is well maintained and looks great for folks who are coming in.”

And now many of them are afraid to go to work, for fear of being racially profiled.

The major studios and guilds have largely been mum on the topic of the raids, save for a statement from IATSE on June 9 saying it was “deeply troubled,” or SAG-AFTRA’s brief statement of support of a local SEIU leader who was injured and detained while protesting.

Agustín, for one, wants to see much more from the industry. The Dodgers recently took a stand, pledging $1 million to support families of immigrants impacted by the ICE raids. Why can’t Hollywood?

“Not only is L.A. County almost 50 percent Latino… it’s almost a reality that we don’t like to talk about,” says the TV writer. “We know who helps run this city, and we’re not going to stand up for them when they’re most needed? I think a society will be judged by how they treat their most vulnerable amongst them. And by not having the guilds, the studios and the networks speaking out against these ICE raids, that to me is just heartbreaking. It’s heartbreaking and not up to our values as Americans, as a city and an industry.”

This is really good news. I'll be sure to spread the word in Korea.

Thank you for writing this