A Crisis is a Terrible Thing to Waste (Except in Hollywood)

As the competition for attention grows, one studio head explains to me that he can take one chance a year

My partner in all this at The Ankler, Janice Min, is at Cannes Lions today, the big advertising confab, and just interviewed YouTube CEO Neal Mohan onstage. She and our team report that up and down the Croisette, the excitement is all about… creators. In the epicenter of glamour of old-time cinema, it’s the creators who are everywhere supplanting the role of Hollywood stars. Fans stop them for selfies and beg them to come to their otherwise forgettable brand parties. A just-published WPP study says that money towards creator-led programming has surpassed traditional media, with a spend this year of $185 billion. YouTube now accounts for 11 percent of all watch time on TVs, making it the first streaming platform to surpass that milestone. Second place is Netflix, at around 8.5 percent.

Which brings me to my point of the day. The world has become exponentially more competitive, with digital offerings that seek to colonize every moment of our waking lives. It only keeps getting busier, all at a time when the world’s consumers’ wallets are stretched ever tighter.

As this is happening, the studios and major entertainment providers have responded to the challenge by making entertainment markedly worse, in some ways, alarmingly worse. Not just the films and shows themselves, but the whole experience of entertainment often feels like it is sliding into some kind of bargain basement decrepitude.

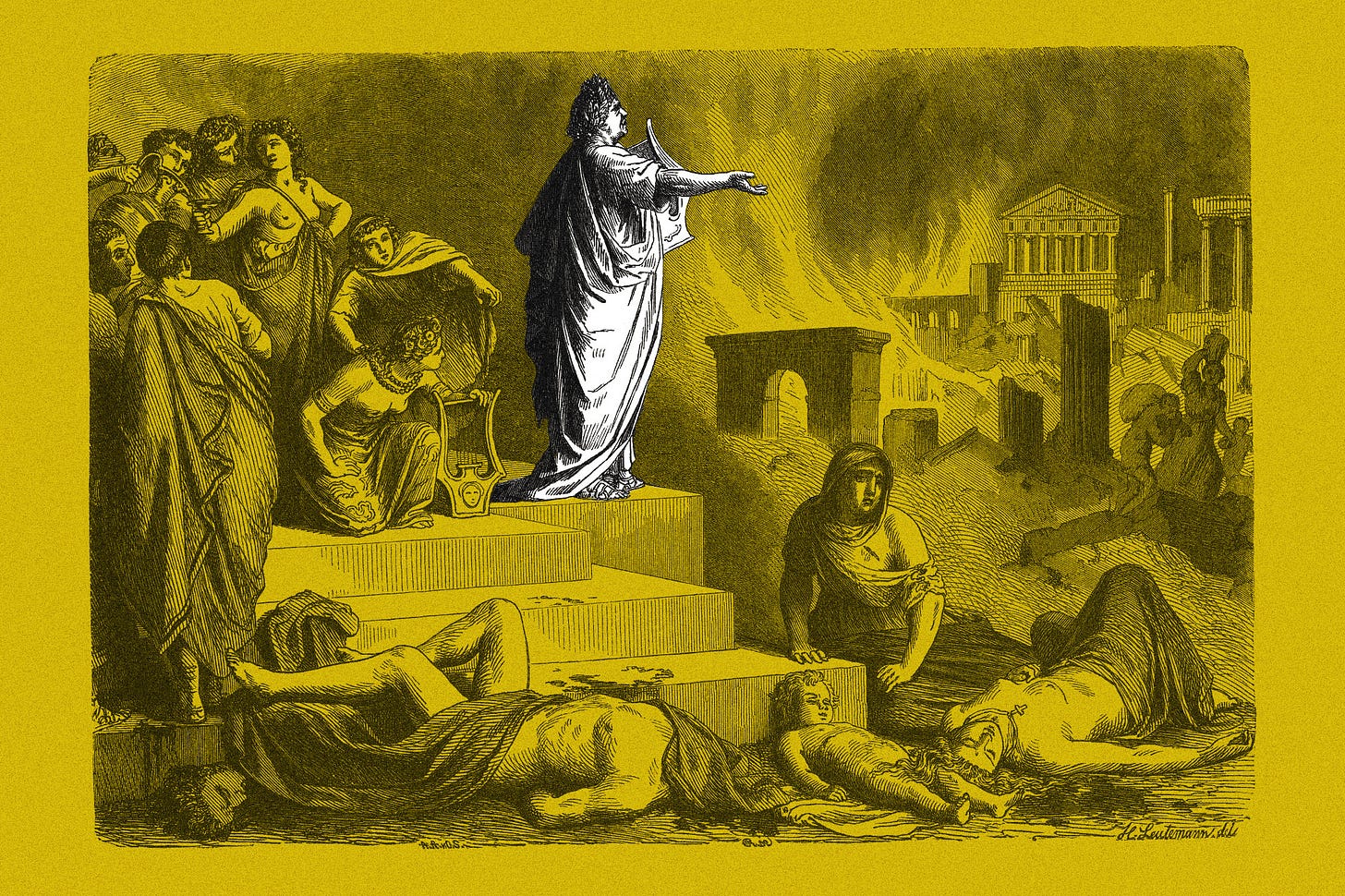

Ideally, when you are faced with an existential crisis, staring into the barrel of your own demise, you’d respond to that by marching into battle with your best foot forward, not, ideally, your worst. Instead, in so many ways, “worst” is how Hollywood seems to be reacting to the challenge. You can rise to the occasion, or you can slump in a corner and wait for it to be done with you.

Needless to say, if you answer a challenge by making your product worse, the odds do not swing in your favor. We can blame external factors all we want, but no one can say that if we go down, we’re going down fighting. More like, we’re going down shrugging.

Now, I don’t think that the titans of entertainment actually want it all to come crashing down (although the possibility that some of them are sleeper agents for an enemy medium is not to be dismissed entirely). It’s more the tragedy of the commons combined with the reigning accountant’s mindset. Everyone would be 100 percent behind someone else doing something about it.

So let’s take a look at the all-too-familiar ways the streaming world and the multiplex alike have shifted their focus away from winning over audiences to milking them for more.

These big issues are familiar, but seeing them through the prism of an industry that no longer prioritizes serving and delighting audiences as its primary focus, it all starts to make sense.

1. The Annoyance Era

This is a factor that extends beyond entertainment. The corporate world has essentially run out of territory to fuel easy, fast, eye-catching growth by bringing in large numbers of new customers. So, growth now comes from upselling its current customers, or more to the point, making the standard level of service so unappealing that it harasses its users to upgrade to a higher tier.

If you’ve flown cross-country in a non-premium coach seat lately, you certainly know all about this, but a similar phenomenon has crept into the streaming experience as well. And frankly, this shift in mindset explains much of business and the studios feel’ feelings about their customer base. The idea that you grow a business by creating a great product and continually improving it is an ancient relic of business school past. Instead, business growth is about capturing a share of a functioning monopoly and squeezing ever more out of your base.

The indispensable Ted Gioia at The Honest Broker newsletter described this phenomenon, vis-à-vis Netflix:

The deeper truth is that you aren’t paying $25 because Netflix’s premium service is getting better. You’re paying extra just to avoid the rising levels of annoyance—and the digital overlords know it.

You should notice that they are raising the premium subscription more than the entry level price. They are flexing, my friends. They know those ads are insufferable, and are going to make it harder for you to avoid them.

We once lived in an industrial economy—built on industry. Then we shifted to a consumer economy—built on consumption. And more recently we lived in a service economy—built on service.

But we now are entering the age of the Annoyance Economy. And it is the inevitable result of corporations battling for your attention.

They monetize your eyeballs—measured in clicks and microseconds—and they will do anything to hold on to them. This increasingly involves annoying, intrusive actions that no business would have dared to implement in a consumer-oriented economy.

We are entering an era where the functional growth of streaming services is based on making basic service worse, which is the pillar of the entire mindset shift of this industry.

Related:

2. The Shrinking Film Palate

The list of genres abandoned by the film studios is now longer than the list of things they will make. Starting with comedy and drama, magically walking away from both halves of the artistic spectrum.

For a while, we’d roll our eyes and mention some film or another, "That would never get made today.” But we’ve really reached the point where we can say nothing would get made today, outside of Big IP 4-Quad spectaculars, and the very occasional fluke that somehow slipped through the system. (One studio head explained to me that he can take one chance a year.)

Just look back at 2005. All these films grossed over $100 million domestically. The legacy studios would make none of them today, unless they were the lightning strike of that year: War of the Worlds, Wedding Crashers, Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Hitch, The Longest Yard, Meet the Fockers, Robots, The Pacifier, The 40-Year-Old Virgin. The nominees for Best Picture from that year: Crash, Brokeback Mountain, Capote, Good Night and Good Luck, Munich. Also, none of which would be made today within the studio system, unless they were that one lightning strike.

There are plenty of execs out there who would love to be taking more swings, but the system has decided, with the very very occasional exceptions, that big and bland is what we do here. You look at that list of films above. That’s a lot of territory Hollywood offered its moviegoing customers not very long ago. Now, they’ve taken it off the shelves.